- Home

- Holly Black

Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

CONTENTS

TITHE

VALIANT

IRONSIDE

THE LAMENT OF LUTIE-LOO

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

TITHE

For my little sister Heidi

And pleasant is the faerie land

But an eerie tale to tell,

Ay at the end of seven years

We pay a tithe to Hell;

I am sae fair and fu o flesh,

I’m feard it be mysel.

—“Young Tam Lin”

PROLOGUE

And malt does more than Milton can

To justify God’s ways to man.

—A. E. HOUSMAN, “TERENCE, THIS IS STUPID STUFF”

Kaye took another drag on her cigarette and dropped it into her mother’s beer bottle. She figured that would be a good test for how drunk Ellen was—see if she would swallow a butt whole.

They were up on stage still, Ellen and Lloyd and the rest of Stepping Razor. It had been a bad set and watching them break down the equipment, she could see that they knew it. It didn’t really matter, the sound system was loud and scratchy and everyone had kept drinking and smoking and shouting so she doubted the manager minded. There had even been a little dancing.

The bartender leered at her again and offered her a drink “on the house.”

“Milk,” Kaye smirked, brushing back her ragged, blond hair and pocketing a couple of matchbooks when his back was turned.

Then her mother was next to her, taking a deep swallow of the beer before spitting it all over the counter.

Kaye couldn’t help the wicked laughter that escaped her lips. Her mother looked at her in disbelief.

“Go help load up the car,” Ellen said, voice hoarse from singing. She was smoothing damp hair back from her face. Her lipstick was rubbed off the inside of her lips but still clung to the edges of her mouth, smudged a little. She looked tired.

Kaye slid off the counter and leapt up onto the stage in one easy move. Lloyd glared at her as she started to pick up the stuff randomly, so she stuck to what was her mother’s. His eyes were glazed. “Hey kid, got any money on you?”

Kaye shrugged and took out a ten-dollar bill. She had more, and he probably knew it—she’d come straight from Chow Fat’s. Delivering might pay crap, but it still paid better than being in a band.

He took the money and ambled off to the bar, probably to get some beer to go.

Kaye hauled an amplifier through the crowd. People mostly got out of her way. The cool autumn air outside the bar was a welcome relief, even stinking as it was with iron and exhaust fumes and the subways. The city always smelled like metal to Kaye.

Once the equipment was loaded up, she went back inside, intent on getting her mother in the car before someone smashed the window and stole the equipment. You couldn’t leave anything in a car in Philly. The last time Ellen’s car had been broken into, they’d done it for a secondhand coat and a bag of towels.

The girl checking IDs at the door frowned at Kaye now that she was solo, but let her in all the same. It was late anyway, almost last call. Ellen was still at the bar, smoking a cigarette and drinking something stronger than beer. Lloyd was talking to a guy with long, dark hair. The man looked too well dressed for the bar. He must have bought a round or something, because Lloyd had his arm over his shoulder and Lloyd wasn’t usually a friendly guy. She caught a flash of the man’s eyes. Cat-yellow, reflecting in the dim light. Kaye shivered.

But then, Kaye saw odd things sometimes. She’d learned to ignore them.

“Car’s loaded,” Kaye told her mother.

Ellen nodded, barely listening. “Can I have a cigarette, honey?”

Kaye fished the pack out of her army-surplus satchel and took out two, handing one to her mother and lighting the other.

Her mother bent close, the smell of whiskey and beer and sweat as familiar as any perfume. “Cigarette kiss,” her mother said in that goofy way that was embarrassing and sweet at the same time, touching the tip of her cigarette to the red tip of Kaye’s and breathing in deeply. Two sucks of smoke and it flared to life.

“Ready to go home?” Lloyd asked. His voice sounded velvety, a shade off of sleazy. Not normal asshole Lloyd voice. Not at all.

Ellen didn’t seem to notice anything. She swallowed what was left of her drink. “Sure.”

A moment later, Lloyd lunged toward Ellen with a suddenness that spoke of violence. Kaye reacted without thinking, throwing herself against him. It was probably only his drunkenness that allowed her slight weight to be enough to throw him off balance. But it worked. He nearly fell, and in an effort to catch himself, dropped what he’d been holding. She only saw the knife when it clattered to the floor.

Lloyd’s face was completely blank, empty of any emotion at all. His eyes were wide and his pupils dilated.

Frank, Stepping Razor’s drummer, grabbed Lloyd’s arm. Lloyd had just enough time to punch Frank in the face before other patrons tackled him and somebody called the police.

By the time the cops got there, Lloyd couldn’t remember anything. He was mad as hell, though, cursing Ellen at the top of his lungs. The police drove Kaye and her mother to Lloyd’s apartment and waited while Kaye packed their clothes and stuff into plastic garbage bags. Ellen was on the phone, trying to find a place for them to crash.

“Honey,” Ellen said finally, “we’re going to have to go to Grandma’s.”

“Did she say it was okay?” Kaye asked, stacking her Grace Slick vinyl albums into an empty orange crate. They hadn’t so much as visited once in the six years that they’d been gone from New Jersey. Ellen barely even spoke to her mother on the holidays before passing the phone to Kaye.

“More or less.” Ellen sounded so tired. “It’ll just be a little while. You can visit that friend of yours.”

“Janet,” Kaye said. She hoped that was who Ellen meant. She hoped her mother wasn’t teasing her. If she had to hear another story about Kaye and her cute imaginary friends . . .

“The one you email from the library. Get me another cigarette, okay, hon?” Ellen tossed a bunch of CDs into the crate.

Kaye picked up a leather jacket of Lloyd’s she’d always liked and lit a cigarette for her mother off the stove burner. No sense in wasting matches.

1

Coercive as coma, frail as bloom

innuendoes of your inverse dawn

suffuse the self;

our every corpuscle become an elf.

—MINA LOY, “MOREOVER, THE MOON,” THE LOST LUNAR BAEDEKER

Kaye spun down the worn, gray planks of the boardwalk. The air was heavy and stank of drying mussels and the crust of salt on the jetties. Waves tossed themselves against the shore, dragging grit and sand between their nails as they were slowly pulled back out to sea.

The moon was high and pale in the sky, but the sun was just going down.

It was so good to be able to breathe, Kaye thought. She loved the serene brutality of the ocean, loved the electric power she felt with each breath of wet, briny air. She spun again, dizzily, not caring that her skirt was flying up over the tops of her black thigh-high stockings.

“Come on,” Janet called. She stepped over the overflowing, leaf-choked gutter, wobbling slightly on fat-heeled p

latform shoes. Her glitter makeup sparkled under the street lamps. Janet exhaled ghosts of blue smoke and took another drag on her cigarette. “You’re going to fall.”

Kaye and her mother had been staying at her grandmother’s a week already, and even though Ellen kept saying they’d be leaving soon, Kaye knew they really had nowhere to go. Kaye was glad. She loved the big old house caked with dust and mothballs. She liked the sea being so close and the air not stinging her throat.

The cheap hotels they passed were long closed and boarded up, their pools drained and cracked. Even the arcades were shut down, prizes in the claw machines still visible through the cloudy glass windows. Rust marks above an abandoned storefront outlined the words SALT WATER TAFFY.

Janet dug through her tiny purse and pulled out a wand of strawberry lipgloss. Kaye spun up to her, fake leopard coat flying open, a run already in her stocking. Her boots had sand stuck to the tops of them.

“Let’s go swimming,” Kaye said. She was giddy with night air, burning like the white-hot moon. Everything smelled wet and feral like it did before a thunderstorm, and she wanted to run, swift and eager, beyond the edge of what she could see.

“The water’s freezing,” Janet said, sighing, “and your hair is fucked up. Kaye, when we get there, you have to be cool. Don’t seem so weird. Guys don’t like weird.”

Kaye paused and seemed to be listening intently, her upturned, kohl-rimmed eyes watching Janet as warily as a cat’s. “What should I be like?”

“It’s not that I want you to be a certain way—don’t you want a boyfriend?”

“Why bother with that? Let’s find incubi.”

“Incubi?”

“Demons. Plural. Like octopi. And we’re much more likely to find them”—her voice dropped conspiratorially—“while swimming naked in the Atlantic a week before Halloween than practically anywhere else I can think of.”

Janet rolled her eyes.

“You know what the sun looks like?” Kaye asked. There was only a little more than a slice of red where the sea met the sky.

“No, what?” Janet said, holding the lipgloss out to Kaye.

“Like he slit his wrists in a bathtub and the blood is all over the water.”

“That’s gross, Kaye.”

“And the moon is just watching. She’s just watching him die. She must have driven him to it.”

“Kaye . . .”

Kaye spun again, laughing.

“Why are you always making shit up? That’s what I mean by weird.” Janet was speaking loudly, but Kaye could barely hear her over the wind and the sound of her own laughter.

“C’mon, Kaye. Remember the faeries you used to tell stories about? What was his name?”

“Which one? Spike or Gristle?”

“Exactly. You made them up!” Janet said. “You always make things up.”

Kaye stopped spinning, cocking her head to one side, fingers sliding into her pockets. “I didn’t say I didn’t.”

The old merry-go-round building had been semi-abandoned for years. Angelic lead faces, surrounded by rays of hair, divided the broken panes. The entire front of it was windowed, revealing the dirt floor, glass glittering against the refuse. Inside, a crude plywood skateboarding ramp was the only remains of an attempt to use the building commercially in the last decade.

Kaye could hear voices echoing in the still air all the way to the street. Janet dropped her cigarette into the gutter. It hissed and was quickly carried away, sitting on the water like a spider.

Kaye hoisted herself up onto the outside ledge and swung her legs over. The window was long gone, but her leg scraped against glass residue as she slid in, fraying her stockings further.

Layers of paint muted the once-intricate moldings inside the carousel building. The ramp in the center of the room was tagged by local spray-paint artists and covered with band stickers and ballpoint pen scrawlings. And then there were the boys.

“Kaye Fierch, you remember me, right?” Doughboy chuckled. He was short and thin, despite his name.

“I think you threw a bottle at my head in sixth grade.”

He laughed again. “Right. Right. I forgot that. You’re not still mad?”

“No,” she said, but her merry mood drained out of her. Janet climbed on top of the skateboard ramp to where Kenny was sitting, a king in his silver flight jacket, watching the proceedings. Handsome, with dark hair and darker eyes. He held up a nearly full bottle of tequila in greeting.

Marcus introduced himself by handing over the bottle he’d been drinking from, making a mock throwing motion before letting her take it. A little splashed on the sleeve of his flannel shirt. “Bourbon. Expensive shit.”

She forced a smile. Marcus resumed gutting a cigar. Even hunched over, he was a big guy. The brown skin on his head gleamed, and she could see where he must have nicked himself shaving.

“I brought you some candy,” Janet said to Kenny. She had candy corn and peanut chews.

“I brought you some candy,” Doughboy mocked in a high, squeaky voice, jumping up on the ramp. “Give it here,” he said.

Kaye walked around the room. It was magnificent, old and decayed and fine. The slow burn of bourbon in her throat was perfect for this place, the sort of thing a man in a summer suit who always wore a hat might drink.

“What flavor of Asian are you?” Marcus asked. He had filled the cigar with weed and was chomping down on one end. The thick, sweet smell almost choked her.

She took another swallow from the bottle and tried to ignore him.

“Kaye! You hear me?”

“I’m half Japanese.” Kaye touched her hair, blond as her mother’s. It was the hair that baffled people.

“Man, you ever see the cartoons there? They have them little, little girls with these pigtails and shit in these short school uniforms. We should have uniforms like that here, man. You ever wear one of those, huh?”

“Shut up, dickhead,” Janet said, laughing. “She went to grade school with Doughboy and me.”

Kenny looped one finger through the belt rings of Janet’s jeans and pulled her over to kiss her.

“Yeah, well, damn.” Marcus laughed. “Won’t you hold up your hair in those pigtails for a second or something? Come on.”

Kaye shook her head. No, she wouldn’t.

Marcus and Doughboy started to play Hacky Sack with an empty beer bottle. It didn’t break as they kicked it boot to boot, but it made a hollow sound. She took another long swallow of bourbon. Her head was already buzzing pleasantly, humming in time with imagined merry-go-round music. She moved farther into the dim room, to where old placards announced popcorn and peanuts for five cents apiece.

Against the far wall was a black, weathered door. It opened jerkily when she pushed it. Moonlight from the windows in the main room revealed only an office with an old desk and a corkboard, yellowed menus still pinned to it. She stepped inside, even though the light switch didn’t work. In a shadowed corner, she found a knob. This door led to a stairwell with only a little light drifting down from the top. She felt her way up the stairs. Dust covered the palms of her hands as she slid them along the railings. She sneezed loudly, then sneezed again.

At the top was a small window lit by the murderess moon, ripe and huge in the sky. Interesting boxes were stacked in the corners. Then her eyes fell on the horse, and she forgot all the rest. He was magnificent—gleaming pearl white and covered with tiny pieces of glued-down mirror. His face was painted with red and purple and gold, and he even had a bar of white teeth and a painted pink tongue with enough space to tuck a sugar cube. It was obvious why he’d been left behind—his legs on all four sides and part of his tail had been shattered. Splinters hung down from where they used to be.

Gristle would have loved this. She had thought that many times since she had left the Shore, six years past. My imaginary friends would have loved this. She’d thought it the first time that she’d seen the city, lit up like never-ending Christmas. But they never came when she

was in Philadelphia. And now she was sixteen and felt like she had no imagination left.

Kaye set the bourbon on the dusty floor and dropped her coat next to it. Then she tried to set the horse up as if he were standing on his ruined stumps. It wobbled unsteadily but didn’t fall. She swung one leg over the beast and dropped onto its saddle, using her feet to keep it steady. She ran her hands down its mane, which was carved in golden ringlets. She touched the painted black eyes and the chipped ears.

The white horse rose on unsteady legs in her mind. The great bulk of the animal was real and warm beneath her. She wove her hands in the mane and gripped hard, slightly aware of a prickling feeling all through her limbs. The horse whinnied softly beneath her, ready to leap out into the cold, black water. She threw back her head.

“Kaye?” A soft voice snapped her out of her daydream. Kenny was standing near the stairs, regarding her blankly. For a moment, though, she was still fierce. Then she felt her cheeks burning.

Caught in the half-light, she could see him better than she had downstairs. Two heavy silver hoops shone in the lobes of his ears. His short, cinnamon hair was mussed and had a slight wave to it, matching the beginnings of a goatee on his chin. Under the flight jacket, his too-tight white T-shirt showed off his body.

He moved toward her, reaching his hand out and then looking at it oddly, as though he didn’t remember deciding to do that. Instead he petted the head of the horse, slowly, almost hypnotically.

“I saw you,” he said. “I saw what you did.”

“Where’s Janet?” Kaye wasn’t sure what he meant. She would have thought he was teasing her except for his serious face, his slow way of speaking.

He was stroking the animal’s mane now. “She was worried about you.” His hand fascinated her despite herself. It seemed like he was tangling it in imaginary hair. “How did you make it do that?”

“Do what?” She was afraid now, afraid and flattered both. There was no mocking or teasing in his face.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

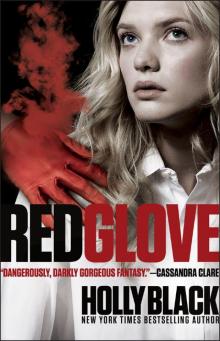

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

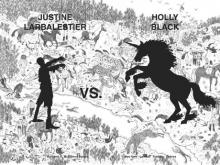

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

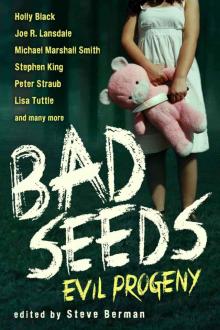

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

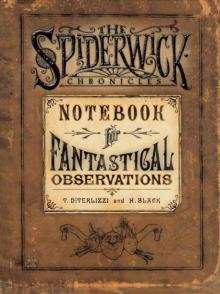

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

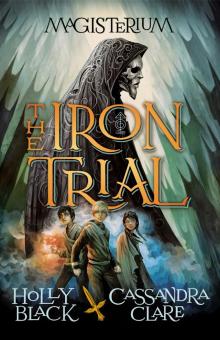

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

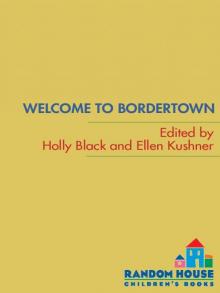

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown