- Home

- Holly Black

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories Read online

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

HOT KEY BOOKS

80–81 Wimpole Street, London W1G 9RE

Owned by Bonnier Books

Sveavägen 56, Stockholm, Sweden

www.hotkeybooks.com

Copyright © Holly Black, 2020

Illustrations © Rovina Cai, 2020

Endpaper art by Kathryn Landis. Copyright © 2019 by Holly Black

Map illustration by Kathleen Jennings. Copyright (c) 2018 by Holly Black.

Drop cap letters copyright © Mednyanszky Zsolt/Shutterstock.com

Running head ornament copyright © Gizele/Shutterstock.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The right of Holly Black and Rovina Cai to be identified as author and illustrator of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

This is a work of fiction. Names, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4714-0999-8

Also available in audio

Hot Key Books is an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

www.bonnierbooks.co.uk

For Brian and Drake,

but mostly for Theo

A

prince of Faerie, nourished on cat milk and contempt, born into a family overburdened with heirs, with a nasty little prophecy hanging over his head—since the hour of Cardan’s birth, he has been alternately adored and despised. Perhaps it’s no surprise that he turned out the way he did; the only surprise is that he managed to become the High King of Elfhame anyway.

Some might think of him as a strong draught, burning the back of one’s throat, but invigorating all the same.

You might beg to differ.

So long as you’re begging, he doesn’t mind a bit.

T

his?” he demands, looking down at the waves far beneath them. “This is how you traveled? What if the enchantment ended while Vivi wasn’t with you?”

“I suppose I would have plummeted out of the air,” Jude tells him with troubling equanimity, her expression saying, Horrible risks are entirely normal to me.

Cardan has to admit that the ragwort steeds are swift and that there is something thrilling about tangling his hand in a leafy mane and racing across the sky. It’s not as though he doesn’t enjoy a little danger, just that he doesn’t gorge himself on it, unlike some people. He cuts his gaze toward his unpredictable, mortal High Queen, whose wild brown hair is blowing around her face, whose amber eyes are alight when she looks at him.

They are two people who ought to have, by all rights, remained enemies forever.

He can’t believe his good fortune, can’t trace the path that got him here.

“Now that I agreed to travel your way,” he shouts over the wind, “you ought to give me something I want. Like a promise you won’t fight some monster just to impress one of the solitary fey who, as far as I can tell, you don’t even like.”

Jude gives him a look. It is an expression that he never once saw her make when they attended the palace school together, yet from the first he saw it, he knew it to be her truest face. Conspiratorial. Daring. Bold.

Even without the look, he ought to know her answer. Of course she wants to fight it, whatever it is. She feels as though she has something to prove at all times. Feels as though she has to earn the crown on her head over and over again.

Once, she told Cardan the story of confronting Madoc after she’d drugged him, but before the poison began to work. While Cardan was in the next room, drinking wine and chatting, she was swinging a sword at her foster father, stalling for time.

I am what you made me, she’d told him as they battled.

Cardan knows Madoc isn’t the only one who made her the way she is. He had a hand in it as well.

It’s absurd, sometimes, the thought that she loves him. He’s grateful, of course, but it feels as though it’s just another of the ridiculous, absurd, dangerous things she does. She wants to fight monsters, and she wants him for a lover, the same boy she fantasized about murdering. She likes nothing easy or safe or sure.

Nothing good for her.

“I’m not trying to impress Bryern,” Jude says. “He says I owe him a favor for giving me a job when no one else would. I guess that’s true.”

“I think his presumption is deserving of a reward,” he tells her, voice dry. “Not, alas, the one you intend to give him.”

She sighs. “If there’s a monster among the solitary Folk, we ought to do something about it.”

There is no reason for him to feel a frisson of dread at those words, no cause for the unease he can’t shake.

“We have knights, sworn to our service,” Cardan says. “You’re cheating one of them out of an opportunity for glory.”

Jude gives a little snort, pushing back her thick, dark hair, trying to tuck it into her golden circlet and out of her eyes. “All queens become greedy.”

He vows to continue this argument later. One of his primary duties as the High King appears to be reminding her she isn’t personally responsible for solving every tedious problem and carrying out every tedious execution in all of Elfhame. He wouldn’t mind causing a little torment here or there, of a nonmurdery sort, but her view of their positions seems overburdened with chores. “Let us meet with this Bryern person and hear his tale. If you must fight this thing, there’s no reason to go alone. You could take a battalion of knights or, failing that, me.”

“You think you’re the equal of a battalion of knights?” she asks with a smile.

He might be, he supposes, although there’s no telling how the mortal world will affect his magic. He did once raise an isle from the bottom of the sea. He wonders if he ought to remind her of that, wonders if she had been impressed. “I believe that I could easily best all of them combined, in a suitable contest. Perhaps one involving drink.”

She kicks her ragwort steed forward with a laugh. “We meet Bryern tomorrow at dusk,” she calls back, and her grin dares him to race. “And after that, we can decide who gets to play the hero.”

Having only recently stopped playing the villain, Cardan thinks again of the winding path of decisions that brought him to this unlikely place, here with her, racing over the sky, planning to end trouble instead of making more of it.

M

any times in his first nine years, Prince Cardan slept in the hay of the stables when his mother didn’t want him in their suite of rooms. It was warm there, and he could pretend he was hiding, could pretend that someone was looking for him. Could pretend that when he was not found, it was only because the spot he’d chosen was so extremely clever.

One night, he was wrapped in a threadbare cloak, listening to the snuffling sounds of faerie steeds, of deer and elk, and even the croaks of great riding toads, when a troll woman stopped outside the pen.

“Princeling,” she said. Her skin was the rough bluish-gray of river rocks, and she had a wart on her chin, from which three golden hairs grew. “You are the youngest of Eldred’s spawn, are you not?”

Cardan blinked up from the hay. “Go away,” he told her as imperiously as he could manage.

That made her laugh. “I ought to saddle you and ride you around the gardens, teach you some manners.”<

br />

He was scandalized. “You’re not supposed to talk to me that way. My father is the High King.”

“Better run and tell him,” she said, then raised her eyebrows and ran fingers over her long golden wart hairs, curling and uncurling them. “No?”

Cardan said nothing. He pressed his cheek against the straw, felt the scratch of it against his skin. His tail twitched anxiously. He knew the High King had no interest in him. Perhaps a brother or sister might intercede on his behalf if they were nearby, and if it amused them to do so, but there was no telling whether it would.

His mother would have slapped the troll woman and ordered her off. But his mother wasn’t coming. And trolls were dangerous. They were strong, hot-tempered, and practically invulnerable. Sunlight turned them to stone—but only until the next nightfall.

The troll woman pointed an accusatory finger at him. “I, Aslog of the West, who brought the giant Girda to her knees, who outwitted the hag of the Fallow Forest, labored in the service of Queen Gliten for seven years. Seven long years I turned the stone of her gristmill and ground wheat so fine and pure that loaves of it were famed all over Elfhame. I was promised land and a title at the end of those seven years. But on the last night, she tricked me into moving away from the millstone and forfeiting the bargain. I came here for justice. I stood before Eldred in the place of the penitent and asked for succor. But your father turned me away, princeling. And do you know why? Because he does not wish to interfere with the lower Courts. But tell me, child, what is the purpose of a High King who will not interfere?”

Cardan was uninterested in politics but well acquainted with his father’s indifference. “If you think I can help you, I can’t. He doesn’t like me, either.”

The troll woman—Aslog of the West, he supposed—scowled down at Cardan. “I am going to tell you a story,” she said finally. “And then I will ask you what meaning you find in the tale.”

“Another one? Is this about Queen Gliten, too?”

“Save your wit for your reply.”

“And if I don’t have an answer?”

She smiled down at him with no small amount of menace. “Then I will teach you an entirely different lesson.”

He thought about calling out to a servant. A groom might be close by, but he had endeared himself to none of them. And what could they do, anyway? Better to humor her and listen to her stupid tale.

“Once upon a time,” Aslog told him, “there was a boy with a wicked tongue.”

Cardan tried not to snort. Despite being a little afraid of her, despite knowing better, he had a tendency toward levity at the worst possible moments.

She went on. “He would say whatever awful thought came into his mind. He told the baker her bread was full of stones, told the butcher he was as ugly as a turnip, and told his own brothers and sisters they were of no more use than the mice who lived in their cupboard and nibbled the crumbs of the baker’s bad bread. And, though the boy was quite handsome, he scorned all the village maidens, saying they were as dull as toads.”

Cardan couldn’t help it. He laughed.

She gave him a dour look.

“I like the boy,” he said with a shrug. “He’s funny.”

“Well, no one else did,” she told him. “In fact, he annoyed the village witch so much that she cursed him. He behaved as though he had a heart of stone, so she gave him one. He would feel nothing—not fear, nor love, nor delight.

“Thereafter, the boy carried something heavy and hard inside his chest. All happiness fled from him. He could find no reason to get up in the morning and even less reason to go to bed at night. Even mockery gave him no pleasure anymore. Finally, his mother told him it was time to go into the world and make his fortune. Perhaps there he would find a way to break the curse.

“And so the boy set out with nothing in his pockets but a crust of the baker’s much-maligned bread. He walked and walked until he came to a town. Although he felt neither joy nor sorrow, he did feel hunger, and that was enough reason to look for work. The boy found a tavernkeeper willing to hire him on to help bottle the beer he brewed. In exchange, the boy would get a bowl of soup, a place by the fire, and a few coins. He labored three days, and when he was finished, the tavern-keeper paid him three copper pennies.

“As he was about to take his leave, the boy’s sharp tongue found something cutting to say, but since his stone heart allowed him to find no amusement in it, for the first time he swallowed his cruel words. Instead, he asked if the man knew anyone else with work for him.

“‘You’re a good lad, so I will tell you this, although perhaps it would be better if I didn’t,’ said the tavernkeeper. ‘The baron is looking to marry off his daughter. She is rumored to be so fearsome that no man can spend three nights in her chambers. But if you do, you’ll win her hand—and her dowry.’

“‘I fear nothing,’ said the boy, for his heart of stone made any feeling impossible.”

Cardan interrupted. “The moral is obvious. The boy wasn’t rude to the innkeeper, so he was given a quest. And because he was rude to the witch, he got cursed. So the boy shouldn’t be rude, right? Rude boys get punished.”

“Ah, but if the witch hadn’t cursed him, he would never have been given the quest, either, would he? He’d be back home, sharpening his wit on some poor candlemaker,” said the troll woman, pointing a long finger at him. “Listen a little longer, princeling.”

Cardan had grown up in the palace, a wild thing to be cosseted by courtiers and scowled at by the High King. No one much liked him, and he told himself he cared little for anyone else. And if he sometimes thought about how he might do something to win his father’s favor, something to make the Court respect him and love him, he kept that to himself. He certainly asked no one to tell him stories, and yet he found it was nice to be told one. He kept that to himself, too.

Aslog cleared her throat and began speaking again. “When the boy presented himself to the baron, the old man looked upon him with sadness. ‘Spend three nights with my daughter, showing no fear, and you shall marry her and inherit all that I have. But I warn you, no man has managed it, for she is under a curse.’

“‘I fear nothing,’ the boy told him.

“‘More’s the pity,’ said the baron.

“By day, the boy did not see the baron’s daughter. As evening came on, the servants bathed him and fed him an enormous meal of roasted lamb, apples, leeks, and bitter greens. Having no dread of what was ahead, he ate his fill, for never had he had a finer meal, and then rested in anticipation of the night ahead.

“Finally, the boy was led to a chamber with a bed at the center and a clawed-up couch tucked into a corner. Outside, he heard one of the servants whispering about what a tragedy it was for such a handsome lad to die so young.”

Cardan was leaning forward now, utterly captivated by the tale.

“He waited as the moon rose outside the window. And then something came in: a monster covered in fur, her mouth filled with three rows of razor-sharp teeth. All other suitors had run from her in terror or attacked her in rage. But the boy’s heart of stone kept him from feeling anything but curiosity. She gnashed her teeth, waiting for him to show fear. When he did not, but rather climbed into the bed, she followed, curling up at the end of it like an enormous cat.

“The bed was very fine, much more comfortable than sleeping on the floor of a tavern. Soon both were asleep. When the boy woke, he was alone.

“The household rejoiced when he emerged from the bedchamber, for no one had ever made it through a single night with the monster. The boy spent the day strolling through the gardens, but although they were glorious, he was troubled that no happiness could yet touch him. On the second night, the boy brought his evening meal with him to the bedchamber and set it on the floor. When the monster came in, he waited for her to eat before he took his portion. She roared in his face, but again he didn’t flee, and when he went to the bed, she followed.

“By the third night, the household w

as in a state of giddy anticipation. They dressed the boy like a bridegroom and planned for a wedding at dawn.”

Cardan heard something in her voice that suggested that wasn’t how things were going to go at all. “And then what?” he demanded. “Didn’t he break the curse?”

“Patience,” said Aslog the troll woman. “The third night, the monster came straight over, nuzzling him with a furred jaw. Perhaps she was excited, knowing that in mere hours her curse might be broken. Perhaps she felt some affection for him. Perhaps the curse compelled her to test his mettle. Whatever the reason, when he didn’t move away, she butted her head playfully against his chest. But she didn’t know her own strength. His back slammed against the wall, and he felt something crack in his chest.”

“His heart of stone,” said Cardan.

“Yes,” said the troll woman. “A great swell of love for his family swept over him. He felt a longing for the village of his childhood. And he was filled with a strange and tender love for her, his cursed bride.

“‘You have cured me,’ he told her, tears wetting his cheeks.

“Tears that the monster took for a sign of fear.

“Her enormous jaws opened, teeth gleaming. Her great nose twitched, scenting prey. She could hear the speeding of his heart. In that moment, she sprang on him and tore him to pieces.”

“That’s a terrible story,” Cardan said, outraged. “He would have been better off if he’d never left home. Or if he’d said something cruel to the tavern-keeper. There is no point to your tale, unless it is that nothing has any meaning at all.”

The troll woman peered down at him. “Oh, I think there’s a lesson in it, princeling: A sharp tongue is no match for a sharp tooth.”

I

t was not so many years after that Cardan found himself staring at the polished door of his eldest brother’s home. On it was a massive carving of a sinister face. As he watched, its wooden mouth twisted up into an even more sinister smile.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

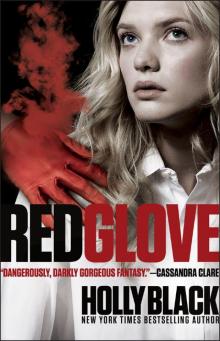

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

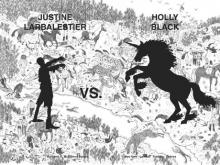

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

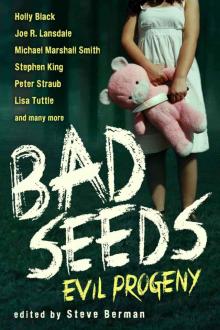

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

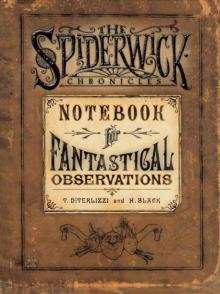

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

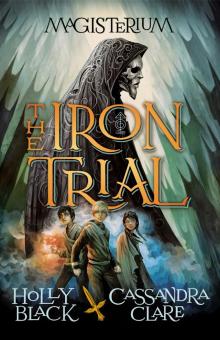

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown