- Home

- Holly Black

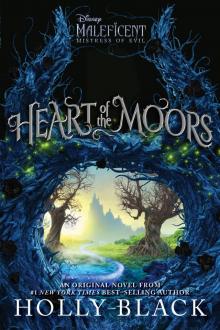

Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors Read online

Copyright © 2019 Disney Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved. Published by Disney Press, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Disney Press, 1200 Grand Central Avenue, Glendale, California 91201.

Cover illustration by Mike Heath

Lettering by Russ Gray

Cover design by Marci Senders

ISBN 978-1-368-05755-4

disneybooks.com

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

FOR EVERYONE WHO HAS DELIGHTED IN THEIR OWN PAIR OF HORNS

—HB

“Once upon a time, there was a wicked faerie called Maleficent, named for both her malice and her magnificence. Her lips were the red of freshly spilled blood, her cheekbones as sharp as the pain of lost love. And her heart was as cold as the deepest part of the ocean.”

The storyteller stood on a cobbled street near the castle, watching with satisfaction as a crowd formed. Children peered up at him openmouthed, henwives stopped in the middle of their shopping, and tradespeople drew close.

Among them was a woman shrouded in a hooded cloak. She stood slightly apart, and even though he couldn’t see her face, something about her drew his eye.

The storyteller had crossed into the kingdom of Perceforest just two days before, and his tale had gotten a good reception in the previous town. Not only had he made a pocketful of copper, but he had been stood a supper at the second-best inn and offered a place by the fire that night. Surely, so near the castle, where there was bound to be more coin, his tale would earn him even greater rewards.

“There was a princess, Aurora, named for the dawn. Her hair was as golden as the crown that would one day rest upon her head. Her eyes were as wide and soft as those of a doe. From the time of her birth, no one could look upon her and not love her. But the wicked faerie hated goodness and put her under a curse.”

All around him, the listeners sucked in their breath. The storyteller was pleased until he realized that they looked alarmed in a way that didn’t seem entirely pleasurable. Something was wrong, but he wasn’t sure what it could be. He had heard a variation of this story all the way out in Weaverton and had taken it upon himself to embroider it a bit. He was sure it was a solid tale, one crafted to flatter the prejudices of the old and inflame the passions of the young.

“Upon her sixteenth birthday, she was to prick her finger on a spindle and die!”

Several listeners cried out in dismay. One of the children clutched another’s hand.

Again, that reaction wasn’t quite right. It shouldn’t affect them so greatly.

It was clearly time to temper the villainy of his tale with a sprinkle of heroism. “But you see, there was a good faerie and—”

A snort came from the hooded figure. The storyteller paused, ruining the momentum of his tale. He was about to pick up the threads and start again when the cloaked woman spoke.

“Is that what happened?” Her voice was melodious, with traces of an accent he couldn’t place. “Truly? Are you sure, storyteller?”

He’d dealt with hecklers before. He gave her his brightest smile, looking around, inviting the crowd to smile with him. “Every word is as true as your standing before me.”

“What would you wager on that?” came the voice. He realized his audience was riveted by this exchange, far more than they had been by his story. “Would you give me your voice? Your firstborn? Your life?”

He laughed nervously.

The woman threw off her cloak, and he took an involuntary step away from her. And then another.

The crowd shrank back in anticipatory horror.

“You—you—” He couldn’t get the words out.

Black horns as sinister as her smile curved back from her head. Her lips were the red of freshly spilled blood. Her cheekbones were as sharp as the pain of lost love. And he was afraid that her heart was indeed as cold as the deepest part of the ocean.

Suddenly, it struck the storyteller that tales all came from somewhere. And that Perceforest was rumored to have a very young queen, one whose name he hadn’t thought to ask but was beginning to guess. Which meant that standing in front of him was…

“You must have guessed my name, storyteller. Won’t you tell me yours?” Maleficent asked.

But it seemed he couldn’t make his mouth work.

She waited a moment, and then her lips curled up into a smile that promised nothing good. “No? No matter. Let this be your fate: You shall be a cat, yowling your stories under windows but never having the satisfaction of getting better than a thrown boot or water dumped on your head for your trouble. Let you remain so until my wicked heart relents.”

Maleficent’s hands sent a whirl of glittering golden light at him, and everyone around the storyteller began to grow. Even the screaming children became enormous, their worn leather shoes the size of his head. He fell to his hands and knees. A curious warmth covered him, as though someone had thrown a fur blanket across his back. He opened his mouth to cry out, but the sound that came from him was a terrible, inhuman yowling.

“I believe you already know the end of the story,” Maleficent said to the crowd. Then she leaped into the sky, her large and powerful wings carrying her away from town in a rush of wind—leaving the storyteller, who had made his living from words, no longer able to speak a one.

When Aurora had been a child in the forest and her only crown had been woven of honeysuckle, she’d thought that the queen of the distant castle must be happy all the time, because everyone had to listen to her and do exactly what she said. Since Aurora had come to the throne, she’d discovered just how wrong she’d been.

For one thing, now everyone seemed to want to tell her what to do.

Her late father’s advisor, a grim-faced elderly man called Lord Ortolan, liked to drone on and on about her royal obligations, which usually involved enacting his strategies for enriching the treasury.

And there were the courtiers—young men and women from noble families throughout the kingdom sent to the palace to be her companions. They took for granted luxuries and delights she’d never known. They taught her formal dances she’d never tried before, and brought in minstrels to sing songs of heroic deeds, and jugglers and acrobats to make her laugh with their antics. They gossiped about one another and speculated about Prince Phillip’s extended visit to her kingdom and whether his pretext of studying Ulsteadian folklore in the libraries of Perceforest was his real reason for remaining. It was all very pleasant, but they still wanted her to do things the way they had a

lways been done. And Aurora wanted change.

She might have expected her godmother, Maleficent, to be sympathetic, but she wasn’t. Instead, Maleficent made endless unhelpful and pointed suggestions about how Aurora would be happier ruling her kingdom from the Moors. And while Aurora lived at the palace, Maleficent stayed away. For the first time in her life, Aurora didn’t have the comfort of Maleficent’s shadow.

It didn’t help that Aurora would be happier in the Moors. The castle was massive and drafty and damp. Wind often whistled down interior corridors. The fireplaces were fond of backing up, giving the elaborately decorated rooms a slight but constant stink of smoke. Worst of all, though, was the iron. Iron latches, iron bars on windows, and iron bands on doors. They were a reminder of the horrible things her father, King Stefan, had done and the even more horrible things he’d wanted to do. Aurora had ordered it all stripped and replaced, but that was such a large undertaking that not even a quarter of the rooms were finished.

She didn’t blame Maleficent for not wanting to visit her there, with all those memories.

But the palace was where Aurora needed to be. Not just because she wanted to know what it was like to be human, but because she had one goal as queen of Perceforest and the Moors—to lead the faeries and humans of both kingdoms into thinking of themselves as belonging to one united land. Her first step was a treaty. The only problem was that no one could agree on anything.

The faeries wanted the humans to stay out of the Moors, but wanted to be able to wander through Perceforest whenever they liked. And the humans wanted to be able to pick up whatever they found lying around in the Moors, even though some of those things were actually mushroom faeries, or crystals that were part of the landscape, or bits of other creatures’ homes.

She had spent the morning trying to make headway, to no avail.

“I hope no one here has offended you,” said Count Alain, drawing Aurora out of her wandering thoughts. The youngest of her important landholders, he was also the most dashing. He had thick midnight hair with a single stripe of white in it, like a very handsome skunk.

“Excuse me?” Aurora asked, puzzled.

He pointed toward the window. “You’ve put a terror in all of us that you might glare at us the way you’ve been glaring at that window.”

“Oh, no,” she said, embarrassed. “I was only lost in my own contemplations.”

On the other side of the great hall, a harpist was entertaining a group of ladies. The royal household had come from their midday dinner and were beginning to consider the games and activities of the evening.

Count Alain stroked his chin, where a thin beard grew. His green eyes sparked with mirth, but sometimes she wondered if he was laughing at her. “I fear we have neglected to amuse you, my queen. Let’s have a hunt in those woods you were staring at.”

“That’s very kind,” Aurora replied, “but I have never liked hunting. I feel too sorry for the creatures.”

“Your sympathy does you credit,” Count Alain said, and before she could respond, he broke into a wide grin. “Yet this you will enjoy! It will be all in fun. A mere excuse for a romp. Surely you’d like to get out of this stuffy castle for a pleasant afternoon.”

She did want to get out of the castle.

“Yes,” said a voice. It was Prince Phillip, just entering the room, mud on his boots. “I can testify you ought to, Your Majesty. Your kingdom is marvelously beautiful right now, with summer turning to autumn.”

With his caramel curls and a careless smile he bestowed on everyone, he turned the heads of most of the women and half the men in the room.

But not hers. Since she had become queen, he was the one she confided in, the one she laughed with when she felt overwhelmed by the task of ruling the kingdom. Just the night before, they’d spent a comfortable evening playing the Game of the Goose in front of the fire, both of them cheating unmercifully.

Friendship with Prince Phillip was safe. He’d already kissed her, after all, even if she didn’t remember it. And he hadn’t even done it because he wanted to, but in the hopes it might end the curse.

It hadn’t, because he didn’t love her. It hadn’t been True Love’s Kiss—which, she told herself, was a relief. After all, love had been the cause of all of Maleficent’s pain. Friendship was better in every way.

“Tell me this,” she said to Phillip. “In your land, is hunting ever done all in fun?”

“In Ulstead,” he said after giving the matter some thought, “while many find hunting enjoyable, we always do it in deadly earnest.”

Aurora turned back to Count Alain. His smile had stiffened. She felt a little guilty.

“I would love to ride in the forest,” Aurora told him. “But it must not be a hunt. And we must not cross into the Moors.”

“Of course, my queen,” replied Count Alain, the spark back in his eyes. “It is well known you take an unaccountably generous view of the faeries.”

Her instinct was to snap at Count Alain that it was the humans who had waged war against the Fair Folk for generations and not the other way around, but she bit back the words. He had grown up being warned about the Moors. Like most of the nobility, he had no experience with the beauty of the place—or the joyful wildness of the beings who lived there.

He’d grown up with lies. She had to convince him that what he’d heard was wrong and believe that he could learn a new way of seeing the faeries. A new way of seeing the world.

If she could get him on her side, he would be a powerfully ally in negotiating the treaty and in changing the minds of her people, especially the younger courtiers, who admired him.

Perhaps the ride was a very good idea.

“We must not cross into the Moors, but we can ride close enough to view them,” Aurora amended. “In fact, the whole court ought to come. We can go tomorrow afternoon and picnic up high enough that we can see inside. The Moors are nothing like the wall of briars that used to surround them. They’re beautiful.”

Count Alain sighed and gave a smile that was only a little forced. “As you wish, my queen.”

Would you like to know what it’s like to lose your wings?

First you have to imagine tasting clouds on your tongue and diving through the sky as you might dive into a pool of water on a hot summer day.

You have to imagine the sun on your face when you’re above the clouds.

You have to imagine never having to be afraid of heights.

And the wings themselves, folded on your back, soft and downy. You have slept every night of your life covered in their warmth.

Then they’re gone. Cut away. A part of you missing, a part that’s still alive and beating against a cage you can’t see.

You feel a raw pain. You are a wound that never closes.

You become plodding and slow. The kingdom you’ve lost is above you, cerulean and out of reach.

You curse the sky.

Curse the air.

Curse the girl.

And then you become the curse.

Aurora hated to sleep. Every night she made excuses to stay up later and later. There were always lists to make, letters to write, endless revisions of the treaty to puzzle over. She wandered around her enormous chamber, stoking the fire and letting her candles burn down so low each wick guttered out in a pool of wax.

But there always came a point when she had to put on her smock and cap and blow out her candle. Then she huddled under her blankets and looked out her window at the stars, trying to convince herself that it was safe to close her eyes, that she would wake up in the morning.

She wasn’t going to sleep for a hundred years.

The enchantment was gone.

The curse was broken.

But most nights Aurora only fell asleep to the pink of dawn blushing on the horizon. Most days she woke up exhausted. Some days she could barely get up.

Yet when the next night came, the fear struck her anew. Falling asleep felt like falling down a deep well, one that she might neve

r claw her way out of.

After tossing and turning for what felt like ages that evening, she got out of bed. Throwing on a heavy gold brocade robe over her smock, she padded through the silent, sleeping household to a fountain on the edge of the royal gardens.

Phillip looked up from where he was sitting, whittling a little flute in the moonlight. “Your Majesty,” he said. “I was hoping you’d come.”

The first time she’d stumbled on him during one of her evening walks, he’d told her that in Ulstead, court parties lasted all night, and he’d grown used to keeping late hours. That time, they’d skipped rocks on an ornamental pond.

“It’s the treaty keeping me up,” she told him with a sigh, although it wasn’t the whole truth. “I’m afraid that the humans and the faeries will never agree to anything. And if I force them, then what’s the use?”

“In Ulstead, the stories of faeries are even worse than those told here, and there are no Fair Folk to contradict them. The kinder tales are no longer told. The only place to even find them is in the Ulsteadian section of your royal library. The people of Perceforest are fortunate, even if they haven’t quite realized it yet.”

Aurora was surprised. “Did you believe those stories?”

Phillip glanced toward the woods. “Until I came here, I had stopped believing in faeries at all.” Then he turned back to her with a smile. “Everything new is hard. But you have a way of making people listen. You’ll convince them.”

She shook her head at his kind words, but they made her feel better. “I hope so. And since I am so convincing, maybe I can convince you not to cheat at a game of moonlight loggets.”

“It’s impossible to cheat at throwing sticks!” he exclaimed, although he was already looking around for the best fallen branch to grab.

“We shall see,” she promised, snatching the stick he’d been eyeing.

That led to a mad laughing scramble. Phillip tried to yank the stick out of Aurora’s hands. Aurora tugged back. But then the stick broke and she landed on the ground.

Phillip looked horrified. “Your pardon,” he said, reaching down a hand. “My behavior was most ungentlemanly.”

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown