- Home

- Holly Black

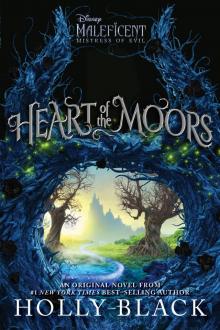

Heart of the Moors Page 2

Heart of the Moors Read online

Page 2

Standing, Aurora dusted off her brocade robe. She felt foolish.

She wanted to tease him. She wanted him to laugh again. She wanted to remind him that they were friends, and friends were allowed to be silly with each other, even if one of them was a queen and the other a prince.

But looking into his eyes, she couldn’t find the right words.

“Let me walk you back to the palace,” he said, offering her his arm and a slightly uncertain smile. “And as a sign of my contrition, I will attempt not to steer you into a ditch.”

“Perhaps I should be the one to steer,” Aurora said lightly.

“Without a doubt,” Phillip returned.

Too early, the curtains were parted and sunlight streamed in. Aurora groaned and tried to bury her head beneath her pillows.

Her chambermaid, Marjory, set down a tray on the end of the bed. Tea, bread and butter, and quince jam.

“Though it’s very improper, your advisor insisted I tell you he would like an audience as soon as you were up,” the girl said, turning to shake out a dress of celery green.

“What do you suppose he wants?” Aurora asked, pushing herself into a sitting position. She took the warm cup and brought it to her lips. Despite having lived in the castle for months, she refused to ignore her servants as the other nobles told her was proper. Her father had been a servant in the castle before he was king, and for all his faults, Aurora felt his rise ought to have proven that no one should be overlooked. “Sit with me. Eat some bread and jam.”

Marjory sat readily, but she didn’t appear to be her usual cheerful self. She was a redhead with very pale freckled skin that grew flushed and blotchy when something upset her, as it apparently had. “Some of the townsfolk have been waiting to see you. Lord Ortolan tried to send them away, but they refuse to go.”

“So you think that’s what he wants to discuss?” Aurora buttered two slices of the bread and pushed one toward Marjory.

The girl took a big bite. “Well, Nanny Stoat says that Lord Ortolan doesn’t want you to talk to any of your people but those who are in his pocket. Forgive me for repeating this, but she says he doesn’t want you to have any ideas that he didn’t give you.”

“Nanny Stoat?” Aurora asked.

“Everyone in the village listens to her,” Marjory said. “If there’s a problem, people say, ‘Take it to Nanny Stoat,’ because she’ll figure out how to make it right.”

“So you think Lord Ortolan doesn’t plan to tell me about the townsfolk?” Aurora asked. “And that he will continue to try to send them away?”

Marjory nodded, although she looked guilty as she did so.

Aurora downed the rest of her tea and got out of bed. She went to her dressing table and started brushing out her hair roughly. “I’d better get down there immediately if I want to speak with them. Tell me anything else you’ve heard—rumors, anything!”

“Wait!” said Marjory, jumping off the bed and forcibly taking the brush from Aurora’s hand. “I’ll braid up your hair as swiftly as I can if you stop doing that to it.”

“Do you know what they want?” Aurora asked, sitting and scowling at herself in the mirror.

The girl began to detangle her hair, separating it down the middle with a clean part. “I heard there was a missing boy. A servant here in the castle. He was one of the grooms, so I didn’t know him particularly.”

Aurora turned in her chair. “Missing? What do you mean?”

“He walked home to see his mother,” Marjory said, valiantly holding on to the sections of hair she’d been braiding, “but he never got there, and no one has seen him since.”

A few minutes later, Aurora ran down the stairs in silken slippers and the green gown.

Lord Ortolan tried to interrupt her as she marched toward the palace doors. “Your Majesty, I am so glad you’re up. If I could command your attention for a moment, there’s a matter of some magical flora along the border—”

“I would like to speak with the family of the missing boy,” she said.

His surprise was evident. “But how did you know?”

“That’s not important,” she said as pleasantly as she could, “since it saves you having to explain the matter to me, which I don’t doubt you were just about to do.”

“Certainly,” he said smoothly. “But we have more immediate important matters to discuss. The business of the boy can wait.”

“No,” Aurora said. “I don’t think it can.”

Lord Ortolan tutted and stalled, but since he couldn’t contradict her command, he eventually called for a footman to show the boy’s family into the solar, a more intimate space than the cavernous great hall.

Aurora was glad. She liked the solar. There was no throne for her to sit in, intimidating everyone who came to make a request of her. Instead, she sat in a cushioned chair and considered ways to find the groom. She would alert her castellan and have his soldiers sweep the land. Perhaps once she’d spoken to the family, she’d have more information about how to focus the search.

A few minutes later, three people entered: a man, holding his hat in his hand, and two older women. The man bowed low, and the women sank into deep curtsies.

“Your boy has gone missing?” Aurora asked.

One of the women stepped forward. She was thin enough that she might be blown over by a curl of smoke. A worn shift hung from her gaunt shoulders. “You must convince the faeries to give back our little Simon.”

“You believe faeries took him?” Aurora said, incredulous. “But why?”

“He had a charmed way with animals,” said the man, and Aurora realized he must be Simon’s father. “And he could play a reed pipe like no one you ever heard, though he’s barely fourteen. Why, even the ancients would be up on their feet and dancing. The Fair Folk are jealous of clever boys like that. They wanted him for themselves.”

This was exactly the reason the country needed a treaty, and exactly the reason one was so hard to negotiate. Aurora was certain that the Fair Folk hadn’t taken the boy—faeries were fond of pipers, sure, but not that fond of them—and she was equally certain that Simon’s family wouldn’t believe her without evidence.

“Could something else have happened to him?” she asked gently.

Lord Ortolan cleared his throat. “The boy was a thief.”

The second woman spoke. Her hair was white and pinned up into a large bun, and her voice shook a little with anger. “Whatever you’ve heard—those other stories, they’re false.”

“Other stories?” Aurora prompted them. “What was he accused of stealing?”

“One of your horses, Your Majesty,” said Lord Ortolan. “And a silver dish besides. The reason no one can find him is that he ran off.”

“That’s not true,” said the man. “He was a good boy. He liked his work. He had no sweetheart and he’d never so much as been to the next town.”

“I will see what I can discover,” Aurora promised.

“The faeries have him,” said the elderly woman with the bun. “Mark my words. Your Majesty, pardon my saying so, but they’re feeling emboldened with you on the throne. Why, just the other day—”

“The cat,” the man said knowingly, nodding.

“Cat?” Aurora asked, and almost instantly regretted the question.

They told her the tale of the storyteller and Maleficent, and though none of them had been present when it happened, Aurora didn’t doubt it was true. By the time they were ushered out, some twenty minutes later, Aurora was left with a heavy heart.

“If you will excuse me…” she said to Lord Ortolan, and began to rise.

“Your Majesty”—he cleared his throat—“you may recall that there was something I wanted to discuss with you earlier.”

“I recall that you didn’t want me to talk to Simon’s family,” she said sharply. Not for the first time, she considered dismissing Lord Ortolan. If only he didn’t have so much influence at court. If only he weren’t the person who understood how so many t

hings in the kingdom worked. It was clear that King Stefan had allowed Lord Ortolan to manage all the practical aspects of Perceforest while he nursed his obsession with Maleficent and argued with her severed wings.

“I didn’t want you to have to waste time speaking with the rabble yourself. After all, it is my duty and privilege to protect you from such things as would naturally bring a young lady discomfort,” Lord Ortolan said smoothly. “But there is something else as well.”

Aurora thought of the breakfast she hadn’t had time to take more than a bite of and all the other things she ought to be doing. She thought of the missing boy and the villagers’ report that Maleficent had turned a storyteller into a cat. She thought of the treaty. She didn’t want to hear about something else that had gone wrong.

But she couldn’t say any of that aloud, especially to Lord Ortolan, who would love to take away all her problems and make all her decisions for her. “Very well,” she said instead. “So what is it?”

He cleared his throat. “Flowers, Your Majesty. A wall of flowers is growing, encircling Perceforest.”

“That sounds pretty…” she said, baffled by his grim tone.

Lord Ortolan frowned and went to a desk where a wooden box rested. “Yes, I can see why it might sound that way. But you will recall the wall of briars that surrounded the Moors, protecting it from humans.”

Aurora waited for him to explain the significance of the briars. “Is our kingdom cut off from the others? Is trade no longer possible?”

Lord Ortolan cleared his throat again, noisily. “It’s not that—not exactly. The roads are clear of flowers—well, the flowers have grown in an arch above the roads. One can still enter and exit Perceforest. But tradespeople are frightened. Many are turning back. And some of our people are afraid to leave for fear the passageways will close.”

He opened the wooden case. Inside was a length of vine with two large roses attached, both flowers the deep black of spilled ink. The outside of each petal shone like polished leather, while the insides had the thick dull nap of velvet. At the end of each petal was a spike like the stinger on the tip of a scorpion’s tail.

“Ah,” said Aurora. “I can see how those might be a little alarming.”

“A little?” Lord Ortolan choked on the words. “This must be your godmother’s doing, but what does she intend?”

“She means no harm to anyone in Perceforest,” Aurora said, stroking one of the black petals. It was extraordinarily soft, aside from the stinger, and very beautiful. Just like her godmother.

“Your Majesty, how can we know?” Lord Ortolan insisted.

“She’s being helpful,” Aurora said with a fond smile, “which means it will be much harder to convince her to stop.”

When Maleficent had placed a crown on Aurora’s head, she hadn’t thought she was putting Aurora in danger. Making her queen of two kingdoms had seemed like a perfect plan. After all, Aurora had wanted to live in the Moors, and she was already the heir to Perceforest. She was a human the faeries loved, and humans would be predisposed to love her, too.

Maleficent believed she would make a wonderful queen.

And she was wonderful.

But the job turned out to be terrible. In the Moors, the only expectation of Queen Aurora was that she guard them from outside threats. But in Perceforest, danger came from all sides—and so did obligations; when her people didn’t want to trick her or cheat her or steal her throne, they wanted her to solve all their problems.

And since Maleficent was the one who had put Aurora in that position, she’d decided to help her—in small ways. Nothing too obvious.

A few seeds planted along the borders. Potions cooked up to guard Aurora against poison. The occasional criminal waking in the royal prisons, begging to confess. Lightning storms drawn from the clouds when it seemed as though Perceforest’s farmlands had gone too long without rain.

And if people looked up in fear when thunder crashed around Aurora, well, perhaps that was no bad thing, either. It was a good reminder that if the humans ever thought to move against her, there would be no one to hold Maleficent back.

But in her travels through Perceforest, she discovered something she hadn’t expected.

The nature of humans.

Maleficent had known a few of them, of course, but, well, a vanishing few. She hadn’t really understood how desperate their lives could be. She hadn’t seen them digging in the dirt for shriveled vegetables, their faces lined and their bodies bent. She hadn’t seen hungry children, or young lovers torn apart by greed, and she hadn’t seen the cruelty neighbors inflicted on one another.

Now she alighted in trees and watched. It made her recall watching over Aurora when she was a baby, neglected by the pixies who were supposed to raise her.

It made her think of Stefan, orphaned and desperate for power.

And it made her certain that getting Aurora away from other humans was the best way to keep her safe.

But as much as she might like to, she couldn’t just drag the girl back to the Moors and keep her there. No, she had to tempt Aurora to spend more and more time among the faeries until she forgot all about the humans. And for that, Maleficent needed something extraordinary.

A palace in the Moors.

A majestic place that would make the castle in Perceforest appear like a dull pile of rubble.

Stretching out her fingers, she began to twist and shape the earth, conjuring up soil and rocks in a spiraling path up a hill. And then she moved on to the palace itself, smoothing out great boulders into walls and thickening vines into staircases. Spires rose into the air, thick with moss, green and magnificent. When she was done, there was a castle where no castle had been, all of leaves and flowers, wood and stone—a living thing, pulsing with magic.

And if a part of her hoped to make up for the hurt she’d already caused Aurora with a truly extravagant gift, if part of the structure itself felt as though it were shaped from her guilt and her fear of losing Aurora again, well, that only made it more beautiful.

Aurora spent the later part of the morning and the early part of the afternoon writing letters and sending pages running to deliver them. She wrote to her castellan, commanding him to send men-at-arms and watchmen to look for the missing groom. She sent another note to her stable master, asking him to provide a description of the boy—and to verify that a horse was missing. And she got a footman to check on the silver dish.

Then she wrote to her godmother.

The other notes could be carried by messengers, but that one could not. Aurora took it up to the dovecote and found a bird she had brought from the Moors. Its wings were white, its head black. Aurora had named it Burr.

“Here you are,” she whispered to the bird as she bound the note to its leg with a gently tied loop of twine. Then she took the bird out, holding the fragile body in her hands. Beneath soft feather, she could feel the rapid beat of its heart. “Take my message straight to Maleficent.”

When she threw the bird into the air, she thought of other wings. Wings trapped by her father, King Stefan. Wings beating their way home.

By the time she was supposed to go out riding with Count Alain and the rest of the court, she was eager to be in the woods, surrounded by the comforting scents of damp earth and fallen leaves. Yet she wondered if she should cancel the outing. Somewhere in her lands, a boy was missing, and while it was entirely possible that he was riding a stolen horse to another town, she couldn’t stop thinking of his family’s pleas for her to believe better of him.

But she reminded herself that being a ruler meant not becoming distracted by every problem in her kingdom. She needed to go on the ride, because if she could show her court the beauty of the Moors, they might yield on the treaty.

It wasn’t easy to focus on the bigger picture, but she had to try.

Marjory talked her into changing her kirtle, and she put on a heavier one of deepest green with an embroidery of vines around the throat. With it, Aurora pulled on warm stockin

gs, riding boots, and a woolen cloak trimmed in wide ribbons.

Marjory also rebraided her hair into a series of plaits that crisscrossed in the back, like the ribbons of a corset. Then, finally, Aurora was racing down to the stables, cloak flying behind her.

But just as she arrived at the stall where her dappled gray horse, Nettle, waited, she heard a familiar buzzing behind her.

Knotgrass, Thistlewit, and Flittle flew into the stables, obviously out of breath. Although the pixies had worn human guises for most of her childhood, they didn’t bother with those now and went almost everywhere carried on their small colorful wings.

“Oh, good, we caught you in time,” said Flittle, tugging on her bluebell-shaped hat.

“What’s the matter, Aunties?” Aurora asked, alarmed.

“You shouldn’t run like that,” scolded Knotgrass, wheezing a little. “Elegant ladies do not hurtle through their castles!”

“Nor do they scowl,” said Flittle at Aurora’s expression.

“And must you ride such a fierce-looking animal?” asked Thistlewit. “It just doesn’t seem safe. Isn’t there a nice rabbit that could carry you? A silky, gentle rabbit. Doesn’t that sound nice?”

“She’s too big for a rabbit,” said Flittle.

“I could make one larger,” said Thistlewit, “or shrink Aurora. Wouldn’t you like to be a bit smaller, my darling?”

Aurora, knowing their magic was erratic at the best of times, shook her head vehemently. “I like myself just the size I am. And I like rabbits just the size they are, too. Now, what is it that you’ve come to talk to me about?”

“Oh, just a very little thing,” said Flittle. “Sometimes your subjects come to us to ask about your preferences. Because of our closeness to you. Why, we think of ourselves as your most trusted counselors, and I am sure you would agree.”

Aurora knew them well enough to be sure that nothing would make them think otherwise, so she held her tongue.

Knotgrass broke in. “Just the other day, we told the cook all about your favorite dishes. Of course, I told her you love trifle, especially the kind with raspberries….”

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown