- Home

- Holly Black

Welcome to Bordertown Page 16

Welcome to Bordertown Read online

Page 16

An arch of some material like poured stone rose above the pavement. Its pillars stood square and simple on the earth; but as they rose higher their surfaces roughened, forked, until the apex of the arch seemed made of braided branches of a stone tree, its bark scaled like a serpent’s skin. In the deep shadows of the carving, specks of light came and went, like stars obscured by a passing cloud. There was nothing to be seen between the pillars but the shifting glow of the Border.

Through that Gate he had lately passed. He could not go that way now.

He turned left, down the street between blocky human-built structures that smelled of oil and dirt, strange spices, and mortality.

Even in darkness, he felt naked and small on the broad way that led from the Gate. Was he a fugitive? He turned at the first street-joining, then turned again and again, until he’d lost the route back. Always he walked downhill. Down was farthest from where he’d begun.

At first he did not properly see the avenues and passages he walked; he did not look, for fear of being looked upon in turn. But as his breath grew short and his steps slowed, he gawked like …

Word and image failed him, as if water had spilled across the surface of his thoughts and washed memory away. Frustration knotted his throat and wetted his eyes. He shook his head fiercely. He would not weep where strangers might see.

Now he noticed that much in the city was not human-built. Beyond the crossing of two streets, he found the way bordered by a high hedge made of glass roses. A hammered silver gate set in the hedge showed him his own face, distorted. Among the nodding, glittering canes above his head he glimpsed silver-latticed windows.

Farther along the street stood a tall, narrow dwelling made (or so it appeared) of polished dark leather sewn with gold wire. Surely humans did not make such places? They seemed common and strange at once, as if he had been told of them but had never seen them.

Standing flank to flank with the coarse brick and stone of the old human city made them stranger still. Even the humans’ sharp-edged boxes were softened with touches of fey beauty: tiny night-blooming vines crept along the mortar between bricks, and stone wore painted tracery that shivered and crawled and shone. Did those of the Blood live side by side with mortal folk here, tossed and jumbled like leaves heaped by the wind?

The city, he knew, rose from the Uncertain Lands like a pin thrust into a map, named not for its founder or for great deeds done on its soil, but for its relation to other places. Bordertown. Had he been here before? Was he here of his own will? He thought not, but he could not be sure.

There were humans here, and people of the True Blood, and chimerae, results of a mating between the two. He considered his feelings and found he did not fear humans, but knew they were untrustworthy, changeable in action and mood as all short-lived things, ill companions and worse servants. But his own kind—ah, from that quarter a threat might arise, if threat there was. For the blood on his shirt most certainly came with him from the Realm.

Before all else, then, he must have another shirt, and a weapon. His fingers dropped of their own will to his belt. It was a purse they sought, but he had none. No name, and now no wealth; the second frightened him nearly as much as the first.

The sky was fading with dawn when he came to another crossing of streets, narrower than many. On his right the ground rose steep in an embankment formed of rough stone. At its foot water ran black and gurgling. He couldn’t tell if it was a natural stream or drainage from somewhere above, but at least it did not smell of offal. And above the wall he glimpsed a garden, where clothing hung on stretched lines.

He slipped and stumbled down the side of the ditch, treading in the icy water and the muck beneath the surface. Now he could reach the stony slope of the bank. He scrambled up, rock edges cutting at his bare toes, his fingers clenching on the outcrops, his shoulders and legs working easily to pull and push him up the slope. Whatever his past, it had made him fit. And the bank was hardly taller than he. He hoisted himself over the last of the stones and rolled into the garden, drowning in the scent of crushed thyme.

The garden belonged to a cottage. It might have been plucked, foundation and all, from a human village and set down in the space left when one of its tall brick neighbors died and was carted away. Even he could see it was unlike the buildings around it. Yet it looked as old, and perhaps older, than they.

It leaned like a tired child against the stiff brown stone structure next door. Even in the gray-blue light he could see it had been painted all awry: the walls purple, the trim around each window and door a different bright color, turquoise, scarlet, yellow, leaf green. He peered through the shadows and saw no motion at the curtained windows, or at the door that opened on a low porch carried in the crook of the cottage like a babe in its nurse’s arm.

He pushed himself upright, the fresh herb scent following him on his palms and knees, and tugged the nearest shirt down from its wooden pins. It was white and soft, knitted like stockings, with cropped sleeves and no collar. Someone had marred the clean white with nine printed characters in a human script, but the garment was clean. He yanked his linen shirt over his head and pulled the new one on in its place. Close-fitting, but he could move freely in it.

“You’re very pretty in that, but it’s still not yours.” The voice was sweet but wandering, like strings plucked at random, and came from the shadows at the back of the cottage.

A woman sat on the edge of the low porch, her long skirt tangled in the rioting blossoms of snapdragon and yarrow planted around it. Her knees supported her elbows, and her chin rested in her two cupped hands.

He thought by her hair she was human—but no, the Blood was in every line of her finely carved face. And humans were clumsy and loud; he would have heard a human walk onto the porch. Why would she dye her hair the color of oak leaves dead on the twig in winter? Was it a sign of mourning? Of low rank?

“Then take pleasure in my beauty while I take the shirt, and all’s paid.” He gave her a smile that might have served him well in his lost past.

She laughed like the clash of rattled silver. “That’s so clever! But I’ve got plenty of beauty. Well, I suppose there’s always room for more, but it’s not the same as a half-pound of coffee beans or two bushels of sheep crap for the garden. Did you know sheep crap makes the best fertilizer? Or is bat shit better? But it’s harder to get bat shit, and it’s not as if you can grow broccoli in caves.”

She was a madwoman. If he had any experience with madness, it was gone with his name, but the idea of it sent a thrill of alarm through his bones. “I take my leave of you, then,” he said, haughty and cold in the hope of alarming her in turn. He stepped backward, in the way he’d come.

“Stop.”

There was no spell in it, but the word was as effective as magic, for the force of command it carried.

The woman stood and walked into the yard, lifting her skirt and her feet to clear the flowers without bruising them. “You’ve trompelated my herb garden enough already.” She stepped close, tilted her head, and peered wide-eyed up into his face, as if he were some rare tamed bird. The top of her brown-dyed head came only to the tip of his nose.

Were her stunted height and her madness of one cause?

“So you’re a T-shirt thief?” she mused in her rising and falling voice. “I don’t think there’s anything in the stories about that. Radishes, yes—or was that salad greens? Anyway, the forfeit for that was a baby, and I really don’t need one of those even if you are pregnant.”

Once he’d had a purse. For all she knew, he had it still. “You shall have recompense in gold. Only let me—”

“Nope, don’t need that either. I know!” She grasped his arm above the elbow and pulled him off-balance, toward the cottage. Her strength was a surprise, her fingers on his already-bruised flesh a trial.

It seemed she meant to pull him straight through the wall of the cottage, and indeed, the wood might have splintered under the force of their progress. But she stopped shor

t an arm’s length from the clapboards. With her free hand she clutched at a sapling tree, slender as a finger, that sprouted from a bed of turned earth along the foundation.

“This,” she said, giving the sapling a shake. “Get this out of my onion bed. That’ll pay for the shirt, don’t you think?”

Perhaps Bordertown thrived on such symbolic barter. But if she chose to set him a trivial task in exchange for what he wanted, why should he protest? Madness and folly could go hand in hand, after all. He gave her a small, mocking bow. “Madam, I accept this forfeit.”

She patted his arm. “Aww, you’re so sweet. Well, soonest begun, soonest too tired to think about doing anything else, right? Let me know when you’re done.” With a flourish of her long, heavy skirt she tramped back to her porch. He heard the closing of the door moments later.

She was gone, and he could leave. But he had agreed to her terms. If he was not bound in fact, he felt so by his honor, and from that feeling he guessed honor was a thing that meant much to him.

He closed his right hand around the whip-slender trunk and tugged. The earth did not give up the tree. He used both hands, but the tree did not shift. He gripped hard and threw all his strength and weight into the balance. The tree was rooted still.

In a rage he yanked and twisted at the slender trunk, calling it foul names with what little breath the struggle left him. The green wood bent and the bark split, but the roots gave not an inch.

The woman was mad, and likely a witch, but the folly, it seemed, was all on his side. Most foolish of all was his pride, which would not let him walk away from his bad bargain. He knelt in the grass and began to probe the earth with his fingers.

The sun stood high overhead when at last he rose to his feet. His back ached, his knees throbbed from finding pointed stones in the grass, and his hands were stiff and sore and stinging with broken blisters on the palms and each grimy finger. But he lifted the little treelet, mauled and half stripped of bark and free at last of the earth, as he might lift a defeated enemy by the throat.

He carried the thing around the corner of the cottage to the little porch. “It is done!” he shouted, and held up the tree as proof.

The flimsy door swung open, and the witch poked out her head, like some little animal from its burrow. “You still here?”

Whatever he had thought she might say, it was not that. “Your forfeit.” He bit back the “Lady” that had nearly followed after, for why should he call a brown-haired witch with a paint-stained skirt and a tumbledown cottage “Lady”? Instead he held the sapling higher.

She stepped onto the porch and stared at his hands. “The shovel was right there,” she said, nodding at the side of the house.

There was, indeed, a shovel leaning against the wall, its pointed blade wedged into a hummock of grass.

He was aware of himself all at once—soil wedged deep under his fingernails and in the creases of his hands, dirt and sweat streaking the once-clean shirt, his hair falling tangled in his face, which must also be dirt- and sweat-streaked, and about him the smell of onions from the stray bulbs he’d unearthed with the tree roots. He clenched his teeth on his anger.

“It pleases you, then, to shame me with a lowly task and an ensorcelled tree?”

She tilted her head like a bird listening for prey underground. “Ensor— No, it’s just an elm. They have a really long taproot. See?” She pointed. “And it’s not lowly if it needs doing, is it? It would have been a lot easier with the shovel, though.”

Was it possible to be a witch and simple? By her manner, there was no malice in her. He set down the tree and lifted his filthy hands. “I would leave this earth with its kin. May I come in to wash?”

“Oh, no. I don’t know you, so that would be stupid. You could be an ax murderer.”

“Had I an ax, you would know it,” he said through gritted teeth.

She shook her head sadly. “Nope. Can’t do it. Around here, if you don’t pay attention to the stories, all sorts of things go wrong.”

“The stories?”

“Myths, legends, fairy tales. You know.”

“No. No, I don’t.” Surely they were human tales, nonsense to frighten children. But the cold, empty place he felt in himself at her words told him it was not so. “I … don’t remember them.” In answer to her look, he found himself saying, beyond reason, “I don’t remember even my name.”

She blinked. “Wow, you are traveling light.”

He had no notion what she meant. Perhaps she saw his confusion and took pity on him—though the thought of pity from her made his skin sting as if scorched—for she added, “There’s the pump. You can clean up there.”

She waved one blunt-nailed, blue-smudged hand toward the bottom of the garden, at an iron contraption that thrust up out of rank grass and gravel. Then she went back inside.

He learned that part of the iron apparatus was a lever, and when it was raised and lowered many times, water coughed and spat and gushed out of the pipe and onto the ground. The learning took long enough to make him angry, but cold water rushing over his hands and arms and head cooled his temper as it did his flesh.

When he lifted his dripping head at last, he found the witch at his elbow with a rough towel and a pottery bowl. “Lunch.”

“And what shall I do for that? Must I cut your grass with a penknife?” The words had sounded clever in his head; coming from his mouth, they were only childish and surly.

But she beamed. “See? You do know the stories!” She thrust the bowl at him. “Free lunch in every box. Well, T-shirt. But that’s better than on a T-shirt, isn’t it?”

The bowl held soup, made of rice and pea pods and vegetables he did not know (or remember) in a distressingly orange opaque broth, but it smelled wholesome. He took the wooden spoon from her, tasted the soup, and was neither struck dead nor turned into any creature. He only then realized how desperately hungry he was. The soup was savory and rich, and he spooned it up with inelegant, embarrassing haste.

The witch sat cross-legged on the grass before him and watched him eat. When he was half-finished and had slowed to a more decorous pace, she said, “So, do you have a name to tell people? If they ask?”

She might offer to name him. He’d have none of that. Though he’d forgotten his own, he knew names were power. “Page,” he replied, remembering the guards at the Gate and their book.

“Oh, of course! Because pages serve.” She smiled and nodded toward the uprooted tree cast upon the lawn.

He did not serve—not her, not anyone. Unless this upwelling of sour-tasting pride was only envy in pride’s clothes.

“Or it’s a blank page,” she went on, talking to the air. “That’s not good. But not all pages are blank, so that’s better.”

He scraped the last of the soup from the bowl and handed it back to her. “May your kindness be returned,” he said, in lieu of thanks.

“It’s true, the world always needs more soup.” She rose and shook out her skirt, as if grass and dust could make an impression among the many-colored smudges of paint on the cloth. “So, Maybe-Blank Page, where are you going?”

Away from the Border was all the answer he had. “Perhaps I should ask that of you. In this place, do not folk seek advice of witches?”

She stared down at him, while a breeze plucked up a strand of her dirt-brown hair and tangled it in her pale lashes. Then she burst into an unbecoming, hooting laugh, pausing only to wipe both hair and tears from her eyes. “Oh, sweetie! I’m not a witch. I’m a painter.”

The laughter stung like a cloud of wasps. “And thus is your poverty accounted for,” he snapped, and flung out an arm to encompass her stained clothes, her sagging, gaudy cottage, the whole of the shabby, human-built warren of a city she lived in. “Were you a witch, you would at least be of use enough to expect a living for your service.”

She fixed him with an examining look, like the stare she’d given him when he’d named her “witch.” But unlike, too. Her seeking eyes were cold

and bright as flecks in granite. “Get a job, you say? Okay.” Her lips stretched in a smile that never knew mirth. “As of now, I’m a witch. And my first spell is …”

She planted her feet wide, raised her arms, and spread her fingers over him. Why did he still sit, frozen as a rabbit fearing the dogs? Flee before she calls down your death!

“This is my curse on you.” Her voice still wandered the scale, but as if the hands that plucked the notes were strong from work or warfare. She drew herself up straight, took a breath that filled her chest, and declared, “You’ll learn who you are from the next person you meet.”

He crouched before her and felt … no different. Should he sense the rush of sorcery? Or did sorcery touch one like air on skin, merely there? He didn’t know.

Her arms fell. “There you go.” She nodded and smiled, cheerful as if there had been no offense between them. “Now I’ve got work to do. An apple a day makes a really slow still life, you know. Scram! Have fun!” She flapped her hands as if herding a flock of hens.

He staggered to his feet and started toward the stone embankment he’d climbed.

“Not through the herb garden, you bozo!” she shouted. “Round the house to the front walk!”

He did not know what a bozo was, but by her tone, it was not much sought after.

He stumbled down the front steps to the street and chose a direction at random. Down, down the hill to where the tumult of trade and traffic made a steady rattle that knocked his thoughts awry. The pavement seemed made of the same poured stone as that which formed the base of the Border Gate; it was gritty and cold and scraped his bare feet. Where the pavement failed, there was broken stone and sometimes mud to hide the sharpest rocks. Before long, no matter how he labored to make his stride even, he was limping.

Wounded things were prey. Well, should anything pounce, he would show it its error. He thought he could manage that.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

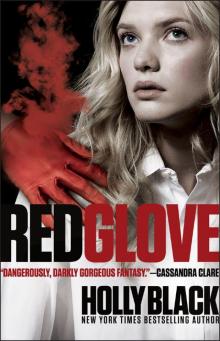

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

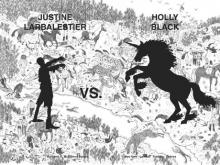

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

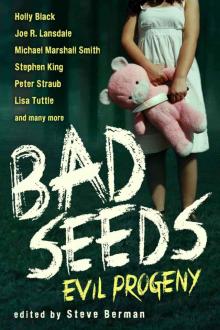

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

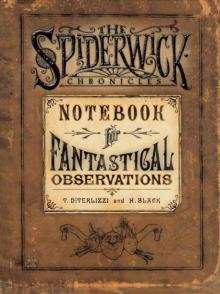

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown