- Home

- Holly Black

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Page 2

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Read online

Page 2

“What the hell are you doing?” he whispered, with a glance to the boy.

“You hit me, or had you forgotten,” she whispered back. “And there’s my son’s alienation of affection.”

He almost straightened. “That’s lawyer talk, Susan,” he said.

“Not here,” she answered. “Not in front of the boy.”

He stepped back quickly as the car growled away from the curb, walked in a daze to his desk and sat there, chin in one palm, staring out the window as the afternoon darkened and a faint drizzle began to fall. His secretary muttered something about a court case the following morning, and Frank nodded until she stared at him, gathered her purse and raincoat and left hurriedly. He continued to nod, not knowing the movement, trying to understand what he had done, what both of them had done to bring themselves to this moment. Ambition, surely. A conflict of generations where women were homebodies and women had careers; where men tried to adjust when they couldn’t have both. But he had tried, he told himself … or he thought he had, until the dishes began to pile up and the dust stayed on the furniture and Damon said does she sing pretty?

It’s always the children who get hurt, he thought angrily.

Held that idea in early December when the separation papers had been prepared and he stood on the front porch watching his car, his wife, and his son drive away from Oxrun Station south toward the city. Damon’s face was in the rear window, nose flat, palms flat, hair pressed down over his forehead. He waved, and Frank answered.

I love you, Dad.

Frank wiped a hand under his nose and went back inside, searched the house for some liquor and, in failing, went straight to bed where he watched the moonshadows make monsters of the curtains.

“Dad,” the boy said, “do I have to go with Mommy?”

“I’m afraid so. The judge … well, he knows better, believe it or not, what’s best right now. Don’t worry, pal. I’ll see you at Christmas. It won’t be forever.”

“I don’t like it, Dad. I’ll run away.”

“No! You’ll do what your mother tells you, you hear me? You behave yourself and go to school every day, and I’ll … call you whenever I can.”

“The city doesn’t like me, Dad. I want to stay at the Station.”

Frank said nothing.

“It’s because of the lady, isn’t it?”

He had stared, but Susan’s back was turned, bent over a suitcase that would not close once it had sprung open again by the front door.

“What are you talking about?” he’d said harshly.

“I told,” Damon said as though it were nothing. “You weren’t supposed to do that.”

When Susan straightened, her smile was grotesque.

And when they had driven away, Damon had said I love you, Dad.

Frank woke early, made himself breakfast and stood at the back door, looking out into the yard. There was a fog again, nothing unusual as the Connecticut weather fought to stabilize into winter. But as he sipped at his coffee, thinking how large the house had become, how large and how empty, he saw a movement beside the cherry tree in the middle of the yard. The fog swirled but he was sure …

He yanked open the door and shouted: “Damon!”

The fog closed and he shook his head. Easy, pal, he told himself; you’re not cracking up yet.

Days.

Nights.

He called Susan regularly, twice a week at pre-appointed times. But as Christmas came and Christmas went, she became more terse, and his son more sullen.

“He’s getting fine grades, Frank, I’m seeing to that.”

“He sounds terrible.”

“He’s losing a little weight, that’s all. Picks up colds easily. It takes a while, Frank, to get used to the city.”

“It’s his home. He will.”

In mid-January Susan did not answer the phone and finally, in desperation, he called the school, was told that Damon had been in the hospital for nearly a week. The nurse thought it was something like pneumonia.

When he arrived that night, the waiting room was crowded with drab bundles of scarves and overcoats, whispers and moans and a few muffled sobs. Susan was standing by the window, looking out at the lights far colder than stars. She didn’t turn when she heard him, didn’t answer when he demanded to know why she had not contacted him. He grabbed her shoulder and spun her around; her eyes were dull, her face pinched with red hints of cold.

“All right,” she said. “All right, Frank, it’s because I didn’t want you to upset him.”

“What in hell are you talking about?”

“He would have seen you and he would have wanted to go back to Oxrun.” Her eyes narrowed. “This is his home, Frank! He’s got to learn to live with it.”

“I’ll get a lawyer.”

She smiled that. “Do that. You do that, Frank.”

He didn’t have to. He saw Damon a few minutes later and could not stay more than a moment. The boy was in dim light and almost invisible, too thin to be real beneath the clear plastic tent and the tubes and the monitors … too frail, the doctor said in professional conciliation, too frail for too long, and Frank remembered the day on the porch with the saucer of milk when he had thought the same thing and had thought nothing of it.

He returned after the funeral, all anger gone. He had accused Susan of murder, knowing at the time how foolish it had been, but feeling better for it in his own absolution. He had apologized. Had been, for the moment, forgiven.

Had stepped off the train, had wept, had taken a deep breath and decided to live on.

Returned to the office the following day, piled folders onto his desk and hid behind them for most of the morning. He looked up only once, when his secretary tried to explain about a new client’s interest, and saw around her waist the indistinct form of his son peering through the window.

“Damon,” he muttered, brushed the woman to one side and ran out to the sidewalk. A fog encased the street whitely, but he could see nothing, not even a car, not even the blinking amber light at the nearest intersection.

Immediately after lunch he dialed Susan’s number, stared at the receiver when there was no answer and returned it to the cradle. Wondering.

“You look pale,” his secretary said softly. She pointed with a pencil at his desk. “You’ve already done a full day’s work. Why don’t you go home and lie down? I can lock up. I don’t mind.”

He smiled, turned as she held his coat for him, touched her cheek … and froze.

Damon was in the window.

No, he told himself … and Damon was gone.

He rested for two days, returned to work and lost himself in a battle over a will probated by a judge he thought nothing less than senile, to be charitable. He tried calling Susan again, and again received no answer.

And Damon would not leave him alone.

When there was fog, rain, clouds, wind … he would be there by the window, there by the cherry tree, there in the darkest corner of the porch.

He knew it was guilt, for not fighting hard enough to keep his son with him, thinking that if he had the boy might still be alive; seeing his face everywhere and the accusations that if the boy loved him, why wasn’t he loved just as much in return?

By February’s end he decided it was time to make a friendly call on a fellow professional, a doctor who shared the office building with him. It wasn’t so much the faces that he saw—he had grown somewhat accustomed to them and assumed they would vanish in time—but that morning there had been snow on the ground; and in the snow by the cherry tree the footprints of a small boy. When he brought the doctor to the yard to show him, they were gone.

“You’re quite right, Frank. You’re feeling guilty. But not because of the boy in and of himself. The law and the leanings of most judges are quite clear—you couldn’t be expected to keep him at his age. You’re still worrying yourself about that woman you kissed and the fact that Damon saw you; and the fact that you think you could have saved his life somehow,

even if the doctors couldn’t; and lastly, the fact that you weren’t able to give him things, like pets, like that cat. None of it is your fault, really. It’s merely something unpleasant you’ll have to face up to. Now.”

Though he didn’t feel all that much better, Frank appreciated the calm that swept over him when the talk was done and they had parted. He worked hard for the rest of the day, for the rest of the week, but he knew that it was not guilt and it was not his imagination and it was not anything the doctor would be able to explain away when he opened his door on Saturday morning and found, lying carefully atop his newspaper, the white-face Siamese. Dead. Its neck broken.

He stumbled back over the threshold, whirled around and raced into the downstairs bathroom where he fell onto his knees beside the bowl and lost his breakfast. The tears were acid, the sobs like blows to his lungs and stomach, and by the time he had pulled himself together, he knew what was happening.

The doctor, the secretary, even his wife … they were all wrong.

There was no guilt.

There was only … Damon.

A little boy with large brown eyes who loved his father. Who loved his father so much that he would never leave him. Who loved his father so much that he was going to make sure, absolutely sure, that he would never be alone.

You’ve been a bad boy, Daddy.

Frank stumbled to his feet, into the kitchen, leaned against the back door. There was a figure by the cherry tree dark and formless; but he knew there was no use running outside. The figure would vanish.

You never did like that cat, Daddy. Or the dogs. Or Mommy.

The telephone rang. He took his time getting to it, stared at it dumbly for several moments before lifting the receiver. He could see straight down the hall and into the kitchen. He had not turned on the overhead light and, as a consequence, could see through the small panes of the back door to the yard beyond. The air outside was heavy with impending snow. Gray. Almost lifeless.

“Frank? Frank, it’s Susan. Frank, I’ve been thinking … about you and me … and what happened.”

He kept his eyes on the door. “It’s done, Sue. Done.”

“Frank, I don’t know what happened. Honest to God, I was trying, really I was. He was getting the best grades in school, had lots of friends … I even bought him a little dog, a poodle, two weeks before he … I don’t know what happened, Frank! I woke up this morning and all of a sudden I was so damned alone. Frank, I’m frightened. Can … can I come home?”

The gray darkened. There was a shadow on the porch, much larger now than the shadow in the yard.

“No,” he said.

“He thought about you all the damned time,” she said, her voice rising into hysteria. “He tried to run away once, to get back to you.”

The shadow filled the panes, the windows on either side, and suddenly there was static on the line and Susan’s voice vanished. He dropped the receiver and turned around.

In the front.

Shadows.

He heard the furnace humming, but the house was growing cold.

The lamp in the living room flickered, died, shone brightly for a moment before the bulb shattered.

He was … wrong.

God, he was wrong!

Damon … Damon didn’t love him.

Not since the night on the corner in the fog; not since the night he had not really tried to locate a cat with a milk-white face.

Damon knew.

And Damon didn’t love him.

He dropped to his hands and knees and searched in the darkness for the receiver, found it and nearly threw it away when the bitterly cold plastic threatened to burn through his fingers.

“Susan!” he shouted. “Susan, damnit, can you hear me?”

A bad boy, Daddy.

There was static, but he thought he could hear her crying into the wind.

“Susan … Susan, this is crazy, I’ve no time to explain, but you’ve got to help me. You’ve got to do something for me.”

Daddy.

“Susan, please … he’ll be back, I know he will. Don’t ask me how, but I know! Listen, you’ve got to do something for me. Susan, damnit, can you hear me?”

Daddy, I’m—

“For God’s sake, Susan, if Damon comes, tell him I’m sorry!”

home.

Treats

Norman Partridge

Monsters stalked the supermarket aisles.

Maddie pushed the squeaky-wheeled cart past a pack of werewolves, smiling when they growled at her because that was the polite thing to do. She couldn’t help staring at the bright eyes inside the plastic masks. Brown eyes, blue and green eyes. Human eyes. Not the eyes that she couldn’t see. Not the black eyes that stared at her from Jimmy’s face, so cold, ordering her here and there without a glint of compassion or love.

“Jimmy, get away from that candy!”

Maddie covered her mouth, fearful that she’d spoken. No, she hadn’t said anything. Besides, Jimmy was at home with them. He’d said that they were preparing for Operation Trojan Horse and he had to speak to them before—

“Jimmy, I’m telling you for the last time … ”

A little ghoul clutching a trick-or-treat bag scampered down the aisle. He tore at the wrapping of a Snickers bar and gobbled a big bite before his mother caught his tattered collar.

“I warned you, young man,” she said, snatching away the bright-orange treat sack. “You’re not going to eat this candy all at once and make yourself sick. You’re allowed one piece a day, remember? That way your treats will last for a long, long time.”

Maddie saw the little boy’s shoulders slump. Her Jimmy had done the same thing last Halloween when Maddie had given him a similar speech, except her Jimmy had been a sad-faced clown, not a ghoul.

And not a general. Not their general.

Maddie raised her hand, as if she could wave off the boy’s mother before she made the same mistake Maddie had made a year earlier. She saw lipstick smears on her fingers and imagined what her face must look like. It had been so long since they’d allowed her to wear cosmetics that she’d made a mess of herself without realizing it. The boy’s mother would see that, and she wouldn’t listen. She’d rush away with her son before Maddie could warn her.

Defeated, the boy stared down at his ghoul-face mirrored in the freshly waxed floor. His mother crumpled his trick-or-treat bag closed, and the moment slowed. Maddie saw herself reaching into her shopping cart, watched her lipstick-smeared fingers tear open a bag of Milk Duds and fling the little yellow boxes down the aisle in a slow, scattering arc. She saw the other Jimmy’s mother yelling at her, the boxes bouncing, the big store windows behind the little ghoul and the iron-gray clouds boiling outside. Wind-driven leaves the color of old skin crackling against the glass.

And then Maddie was screaming at the little ghoul. “Eat your candy! Eat it now! Don’t let them come after it!”

She paid for the Milk Duds, of course, and for all the other candy that she had heaped into the shopping cart. The manager didn’t complain. Maddie knew that the ignorant man only wanted her out of his store.

He thought that she was crazy.

Papery leaves clawed at her ankles as she loaded the candy into the back of the station wagon. She smiled, remembering the other Jimmy, the ghoul Jimmy, gobbling Milk Duds. Other monsters had joined in the feast. Werewolves, Frankensteins, zombies. Maddie prayed that they’d all have awful stomachaches. Then they’d stay home, snuggled in front of their television sets. They wouldn’t come knocking at her door tonight. They’d be safe from her Jimmy and his army.

Maddie climbed into the station wagon and slammed the door. She pretended not to notice Jimmy’s friends in the back seat. It was easy, because she couldn’t see them, couldn’t see their black eyes. But she could feel their presence nonetheless.

Slowly, Maddie drove home. Little monsters stood on front porches and watched the gray sky, waiting intently for true darkness, when they would descend on the neighbo

rhood in search of what Jimmy wanted to give them. Maddie glanced in the rearview mirror at the grocery bags in the back of the station wagon. Even in brown paper, even wrapped in plastic, she could smell the sugar. It was the only smell she knew anymore, and she tasted it in the back of her throat.

God, she’d been tasting it for a year now.

“Mommy,” Jimmy had cried, “you said my candy would last. Now look at it. Look at them. They ruined it. I want new candy. I want it now!”

But Jimmy’s whining had been a lie. Maddie knew that now. Jimmy hadn’t wanted the candy. They had wanted it, and they’d coaxed Jimmy into getting it for them. And they scared her, even if they didn’t scare her son. They’d always scared her.

Because they were everywhere. In the cupboards. Under the floor. In the garden and under the rim of the toilet seat. Maddie’s house swelled with them. And when she went to work, they were there, too, watching her through the windows. Black eyes she couldn’t see, staring. Through the winter cold, through the summer heat, they were always there. Studying her. Never resting.

They had her son, too. He had a million fathers now, all who cared for him more than the man who’d given him his face and his last name before disappearing beneath a wave of unpaid bills. They nested in Jimmy’s room and traveled in his lunch box. Jimmy took them places and showed them things. He taught them about the town, and they told him how smart he was. They made him a general and swore to obey his commands.

Maddie pulled into the driveway and cut the engine. She sat in the quiet car, dreading the house. Inside, Jimmy’s legions waited. Jimmy waited, too. But Jimmy wasn’t a sad-faced clown anymore. Now he was a great leader, and he was about to attack.

The sky rumbled.

Heavy raindrops splattered the windshield.

Maddie almost smiled but caught herself just in time. She glanced in the rearview mirror and pretended to wipe at her smeared lipstick, but really she was looking for Jimmy’s spies.

She wished that she could see their eyes.

Jimmy was in the basement, telling the story of the Trojan horse. They stood at attention in orderly black battalions, listening to every word. Maddie didn’t know how they tolerated it. Jimmy had told them the story at least a hundred times.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

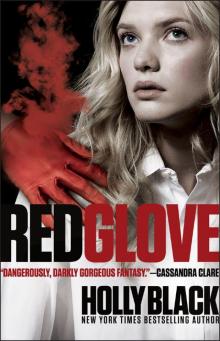

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

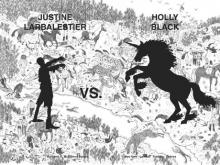

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

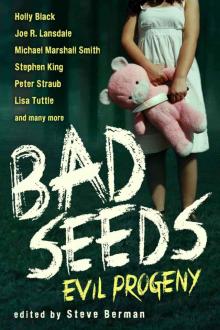

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

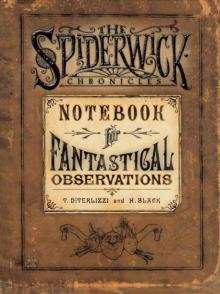

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown