- Home

- Holly Black

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Page 2

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Read online

Page 2

“Severin,” I say.

The smith looks at me, obviously surprised that I have spoken. Then his gaze returns to the High King. “I beg you to allow me to return to the High Court.”

Cardan blinks a few times, as though trying to focus on the petitioner in front of him. “So you were yourself exiled? Or you chose to leave?”

I recall Cardan’s telling me a little about Severin, but he hadn’t mentioned Grimsen. I’ve heard of him, of course. He’s the blacksmith who made the Blood Crown for Mab and wove enchantments into it. It’s said he can make anything from metal, even living things—metal birds that fly, metal snakes that slither and strike. He made the twin swords, Heartseeker and Heartsworn, one that never misses and the other that can cut through anything. Unfortunately, he made them for the Alderking.

“I was sworn to him, as his servant,” says Grimsen. “When he went into exile, I was forced to follow—and in so doing, fell into disfavor myself. Although I made only trinkets for him in Fairfold, I was still considered to be his creature by your father.

“Now, with both of them dead, I crave permission to carve out a place for myself here at your Court. Punish me no further, and my loyalty to you will be as great as your wisdom.”

I look at the little smith more closely, suddenly sure he’s playing with words. But to what end? The request seems genuine, and if Grimsen’s humility is not, well, his fame makes that no surprise.

“Very well,” Cardan says, looking pleased to be asked for something easy to give. “Your exile is over. Give me your oath, and the High Court will welcome you.”

Grimsen bows low, his expression theatrically troubled. “Noble king, you ask for the smallest and most reasonable thing from your servant, but I, who have suffered for such vows, am loath to make them again. Allow me this—grant that I may show you my loyalty in my deeds, rather than binding myself with my words.”

I put my hand on Cardan’s arm, but he shrugs off my cautioning squeeze. I could say something, and he would be forced—by prior command—to at least not contradict me, but I don’t know what to say. Having the smith here, forging for Elfhame, is no small thing. It is worth, perhaps, the lack of an oath.

And yet, something in Grimsen’s gaze looks a little too self-satisfied, a little too sure of himself. I suspect a trick.

Cardan speaks before I can puzzle anything more out. “I accept your condition. Indeed, I will give you a boon. An old building with a forge sits on the edge of the palace grounds. You shall have it for your own and as much metal as you require. I look forward to seeing what you will make for us.”

Grimsen bows low. “Your kindness shall not be forgotten.”

I mislike this, but perhaps I’m being overcautious. Perhaps it’s only that I don’t like the smith himself. There’s little time to consider it before another petitioner steps forward.

A hag—old and powerful enough that the air around her seems to crackle with the force of her magic. Her fingers are twiggy, her hair the color of smoke, and her nose like the blade of a scythe. Around her throat, she wears a necklace of rocks, each bead carved with whorls that seem to catch and puzzle the eye. When she moves, the heavy robes around her ripple, and I spy clawed feet, like those of a bird of prey.

“Kingling,” the hag says. “Mother Marrow brings you gifts.”

“Your fealty is all I require.” Cardan’s voice is light. “For now.”

“Oh, I’m sworn to the crown, sure enough,” she says, reaching into one of her pockets and drawing out a cloth that looks blacker than the night sky, so black that it seems to drink the light around it. The fabric slithers over her hand. “But I have come all this way to present you with a rare prize.”

The Folk do not like debt, which is why they will not repay a favor with mere thanks. Give them an oatcake, and they will fill one of the rooms of your house with grain, overpaying to push debt back onto you. And yet, tribute is given to High Kings all the time—gold, service, swords with names. But we don’t usually call those things gifts . Nor prizes .

I do not know what to make of her little speech.

Her voice is a purr. “My daughter and I wove this of spider silk and nightmares. A garment cut from it can turn a sharp blade, yet be as soft as a shadow against your skin.”

Cardan frowns, but his gaze is drawn again and again to the marvelous cloth. “I admit I don’t think I’ve seen its equal.”

“Then you accept what I would bestow upon you?” she asks, a sly gleam in her eye. “I am older than your father and your mother. Older than the stones of this palace. As old as the bones of the earth. Though you are the High King, Mother Marrow will have your word.”

Cardan’s eyes narrow. She’s annoyed him, I can see that.

There’s a trick here, and this time I know what it is. Before he can, I start speaking. “You said gifts , but you have only shown us your marvelous cloth. I am sure the crown would be pleased to have it, were it freely given.”

Her gaze comes to rest on me, her eyes hard and cold as night itself. “And who are you to speak for the High King?”

“I am his seneschal, Mother Marrow.”

“And will you let this mortal girl answer for you?” she asks Cardan.

He gives me a look of such condescension that it makes my cheeks heat. The look lingers. His mouth twists, curving. “I suppose I shall,” he says finally. “It amuses her to keep me out of trouble.”

I bite my tongue as he turns a placid expression on Mother Marrow.

“She’s clever enough,” the hag says, spitting out the words like a curse. “Very well, the cloth is yours, Your Majesty. I give it freely. I give you only that and nothing more.”

Cardan leans forward as though they are sharing a jest. “Oh, tell me the rest. I like tricks and snares. Even ones I was nearly caught in.”

Mother Marrow shifts from one clawed foot to the other, the first sign of nerves she’s displayed. Even for a hag with bones as old as she claimed, a High King’s wrath is dangerous. “Very well. An’ you had accepted all I would bestow upon you, you would have found yourself under a geas, allowing you to marry only a weaver of the cloth in my hands. Myself—or my daughter.”

A cold shudder goes through me at the thought of what might have happened then. Could the High King of Faerie have been compelled into such a marriage? Surely there would have been a way around it. I thought of the last High King, who never wed.

Marriage is unusual among the rulers of Faerie because once a ruler, one remains a ruler until death or abdication. Among commoners and the gentry, faerie marriages are arranged to be gotten out of—unlike the mortal “until death do us part,” they contain conditions like “until you shall both renounce each other” or “unless one strikes the other in anger” or the cleverly worded “for the duration of a life” without specifying whose. But a uniting of kings and/or queens can never be dissolved.

Should Cardan marry, I wouldn’t just have to get him off the throne to get Oak on it. I’d have to remove his bride as well.

Cardan’s eyebrows rise, but he has all the appearance of blissful unconcern. “My lady, you flatter me. I had no idea you were interested.”

Her gaze is unflinching as she passes her gift to one of Cardan’s personal guard. “May you grow into the wisdom of your counselors.”

“The fervent prayer of many,” he says. “Tell me. Has your daughter made the journey with you?”

“She is here,” the hag says. A girl steps from the crowd to bow low before Cardan. She is young, with a mass of unbound hair. Like her mother, her limbs are oddly long and twig-like, but where her mother is unsettlingly bony, she has a kind of grace. Maybe it helps that her feet resemble human ones.

Although, to be fair, they are turned backward.

“I would make a poor husband,” Cardan says, turning his attention to the girl, who appears to shrink down into herself at the force of his regard. “But grant me a dance, and I will show you my other talents.”

I

give him a suspicious look.

“Come,” Mother Marrow says to the girl, and grabs her, not particularly gently, by the arm, dragging her into the crowd. Then she looks back at Cardan. “We three will meet again.”

“They’re all going to want to marry you, you know,” Locke drawls. I know his voice even before I look to find that he has taken the position that Mother Marrow vacated.

He grins up at Cardan, looking delighted with himself and the world. “Better to take consorts,” Locke says. “Lots and lots of consorts.”

“Spoken like a man about to enter wedlock,” Cardan reminds him.

“Oh, leave off. Like Mother Marrow, I have brought you a gift.” Locke takes a step toward the dais. “One with fewer barbs.” He doesn’t look in my direction. It’s as though he doesn’t see me or that I am as uninteresting as a piece of furniture.

I wish it didn’t bother me. I wish I didn’t remember standing at the very top of the highest tower on his estate, his body warm against mine. I wish he hadn’t used me to test my sister’s love for him. I wish she hadn’t let him.

If wishes were horses , my mortal father used to say, beggars would ride . Another one of those phrases that makes no sense until it does.

“Oh?” Cardan looks more puzzled than intrigued.

“I wish to give you me —as your Master of Revels,” Locke announces. “Grant me the position, and I will make it my duty and pleasure to keep the High King of Elfhame from being bored.”

There are so many jobs in a palace—servants and ministers, ambassadors and generals, advisors and tailors, jesters and makers of riddles, grooms for horses and keepers of spiders, and a dozen other positions I’ve forgotten. I didn’t even know there was a Master of Revels. For all I know, he invented the position.

“I will serve up delights you’ve never imagined.” Locke’s smile is infectious. He will serve up trouble, that’s for sure. Trouble I have no time for.

“Have a care,” I say, drawing Locke’s attention to me for the first time. “I am sure you would not wish to insult the High King’s imagination.”

“Indeed, I’m sure not,” Cardan says in a way that’s difficult to interpret.

Locke’s smile doesn’t waver. Instead, he hops onto the dais, causing the knights on either side to move immediately to stop him. Cardan waves them away.

“If you make him Master of Revels—” I begin, quickly, desperately.

“Are you commanding me?” Cardan interrupts, eyebrow arched.

He knows I can’t say yes, not with the possibility of Locke’s overhearing. “Of course not,” I grind out.

“Good,” Cardan says, turning his gaze from me. “I’m of a mind to grant your request, Locke. Things have been so very dull of late.”

I see Locke’s smirk and bite the inside of my cheek to keep back the words of command. It would have been so satisfying to see his expression, to flaunt my power in front of him.

Satisfying, but stupid.

“Before, Grackles and Larks and Falcons vied for the heart of the Court,” Locke says, referring to the factions that preferred revelry, artistry, or war. Factions that fell in and out of favor with Eldred. “But now the Court’s heart is yours and yours alone. Let’s break it.”

Cardan looks at Locke oddly, as though considering, seemingly for the first time, that being High King might be fun . As though he’s imagining what it would be like to rule without straining against my leash.

Then, on the other side of the dais, I finally spot the Bomb, a spy in the Court of Shadows, her white hair a halo around her brown face. She signals to me.

I don’t like Locke and Cardan together—don’t like their idea of entertainments—but I try to put that aside as I leave the dais and make my way to her. After all, there is no way to scheme against Locke when he is drawn to whatever amuses him most in the moment.…

Halfway to where the Bomb’s standing, I hear Locke’s voice ring out over the crowd. “We will celebrate the Hunter’s Moon in the Milkwood, and there the High King will give you a debauch such that bards will sing of, this I promise you.”

Dread coils in my belly.

Locke is pulling a few pixies from the crowd up onto the dais, their iridescent wings shining in the candlelight. A girl laughs uproariously and reaches for Cardan’s goblet, drinking it to the dregs. I expect him to lash out, to humiliate her or shred her wings, but he only smiles and calls for more wine.

Whatever Locke has in store, Cardan seems all too ready to play along. All Faerie coronations are followed by a month of revelry—feasting, boozing, riddling, dueling, and more. The Folk are expected to dance through the soles of their shoes from sundown to sunup. But five months after Cardan’s becoming High King, the great hall remains always full, the drinking horns overflowing with mead and clover wine. The revelry has barely slowed.

It has been a long time since Elfhame had such a young High King, and a wild, reckless air infects the courtiers. The Hunter’s Moon is soon, sooner even than Taryn’s wedding. If Locke intends to stoke the flames of revelry higher and higher still, how long before that becomes a danger?

With some difficulty, I turn my back on Cardan. After all, what would be the purpose in catching his eye? His hatred is such that he will do what he can, inside of my commands, to defy me. And he is very good at defiance.

I would like to say that he always hated me, but for a brief, strange time it felt as though we understood each other, maybe even liked each other. Altogether an unlikely alliance, begun with my blade to his throat, it resulted in his trusting me enough to put himself in my power.

A trust that I betrayed.

Once, he tormented me because he was young and bored and angry and cruel. Now he has better reasons for the torments I am sure he dreams of inflicting on me once a year and a day is gone. It will be very hard to keep him always under my thumb.

I reach the Bomb and she shoves a piece of paper into my hand. “Another note for Cardan from Balekin,” she says. “This one made it all the way to the palace before we intercepted it.”

“Is it the same as the first two?”

She nods. “Much like. Balekin tries to flatter our High King into coming to his prison cell. He wants to propose some kind of bargain.”

“I’m sure he does,” I say, glad once again to have been brought into the Court of Shadows and to have them still watching my back.

“What will you do?” she asks me.

“I’ll go see Prince Balekin. If he wants to make the High King an offer, he’ll have to convince the High King’s seneschal first.”

A corner of her mouth lifts. “I’ll come with you.”

I glance back at the throne again, making a vague gesture. “No. Stay here. Try to keep Cardan from getting into trouble.”

“He is trouble,” she reminds me, but doesn’t seem particularly worried by her own worrying pronouncement.

As I head toward the passageways into the palace, I spot Madoc across the room, half in shadow, watching me with his cat eyes. He isn’t close enough to speak, but if he were, I have no doubt what he would say.

Power is much easier to acquire than it is to hold on to.

Balekin is imprisoned in the Tower of Forgetting on the northernmost part of Insweal, Isle of Woe. Insweal is one of the three islands of Elfhame, connected to Insmire and Insmoor by large rocks and patches of land, populated with only a few fir trees, silvery stags, and the occasional treefolk. It’s possible to cross between Insmire and Insweal entirely on foot, if you don’t mind leaping stone to stone, walking through the Milkwood by yourself, and probably getting at least somewhat wet.

I mind all those things and decide to ride.

As the High King’s seneschal, I have the pick of his stables. Never much of a rider, I choose a horse that seems docile enough, her coat a soft black color, her mane in complicated and probably magical knots.

I lead her out while a goblin groom brings me a bit and bridle.

Then I swing onto her

back and direct her toward the Tower of Forgetting. Waves crashing against the rocks beneath me. Salt spray misting the air. Insweal is a forbidding island, large stretches of its landscape bare of greenery, just black rocks and tide pools and a tower threaded through with cold iron.

I tie the horse to one of the black metal rings driven into the stone wall of the tower. She whickers nervously, her tail tucked hard against her body. I touch her muzzle in what I hope is a reassuring way.

“I won’t be long, and then we can get out of here,” I tell her, wishing I’d asked the groom for her name.

I don’t feel so differently from the horse as I knock on the heavy wooden door.

A large, hairy creature opens it. He’s wearing beautifully wrought plate armor, blond fur sticking out from any gaps. He’s obviously a soldier, which used to mean he would treat me well, for Madoc’s sake, but now might mean just the opposite.

“I am Jude Duarte, seneschal to the High King,” I tell him. “Here on the crown’s business. Let me in.”

He steps aside, pulling the door open, and I enter the dim antechamber of the Tower of Forgetting. My mortal eyes adjust slowly and poorly to the lack of light. I do not have the faerie ability to see in near darkness. At least three other guards are there, but I perceive them more as shapes than anything else.

“You’re here to see Prince Balekin, one supposes,” comes a voice from the back.

It is eerie not to be able to see the speaker clearly, but I pretend the discomfort away and nod. “Take me to him.”

“Vulciber,” the voice says. “You take her.”

The Tower of Forgetting is so named because it exists as a place to put Folk when a monarch wants them struck from the Court’s memory. Most criminals are punished with clever curses, quests, or some other form of capricious faerie judgment. To wind up here, one has to have really pissed off someone important.

The guards are mostly soldiers for whom such a bleak and lonely location suits their temperament—or those whose commanders intend them to learn humility from the position. As I look over at the shadowy figures, it’s hard to guess which sort they are.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

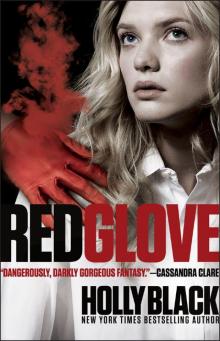

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

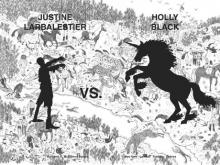

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

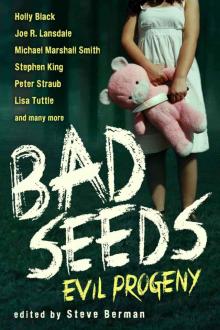

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

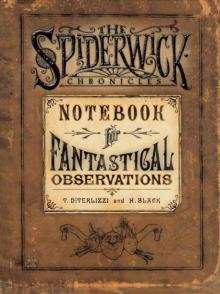

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

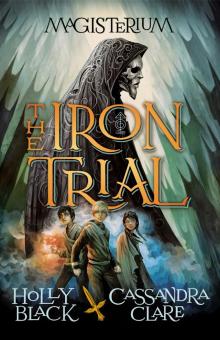

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

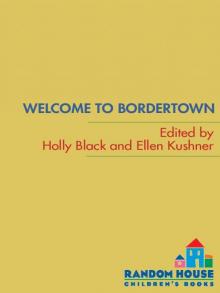

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown