- Home

- Holly Black

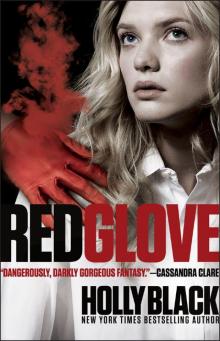

Red Glove (2) Page 21

Red Glove (2) Read online

Page 21

“Like who’s a worker?” she asks. “You’re making money off those bets too, aren’t you?”

Daneca narrows her eyes at me. “Cassel, is that true?”

“You don’t understand,” I say, turning to her. “If I suddenly pick and choose what bets to take, then it would seem like I knew something—like I was protecting someone. I sit with you three; everyone would assume I was protecting one of you. Plus people would stop telling me what’s going on—what rumors are being spread. And I couldn’t spread any rumors of my own. I wouldn’t be any help.”

“Yeah, and you’d have to take a stand, too,” Lila says. “People might even think you’re a worker. I know how much you would hate that.”

“Lila—,” I say. “I swear to you, there’s a stupid rumor about every new kid that comes to Wallingford. No one believes them. If I didn’t take those bets, I would basically confirm that you and Greg—” I stumble over the words and start over, not wanting to piss her off any worse than I already have. “It would make everyone think the rumor was true.”

“I don’t care,” Lila says. “You’re the one that’s making me into a joke.”

“I’m sorry—”, I start, but she cuts me off.

“Don’t con me.” She reaches into her pocket and slaps five twenty-dollar bills down on the table. The glasses rattle, liquid sloshing. “A hundred bucks says that Lila Zacharov and Greg Harmsford did it. What are my odds?”

She doesn’t know that Greg’s never coming back to Wallingford. She doesn’t know that Audrey hates her guts. I look automatically toward his old table, hoping that Audrey can’t overhear any of this.

“Good,” I force out. “Your odds are good.”

“At least I’ll make a profit,” she says. Then she gets up and stalks out of the dining hall.

I rest my forehead against the table and fold my arms on top of my head. I really can’t win today.

“You gave back that money,” Sam says. “Why didn’t you tell her?”

“Not all of it,” I say. “I didn’t want her to know that they were betting on her, so I just took whatever envelopes people handed me when Lila was around. And I did take bets on who was a worker. I thought I was doing the right thing. Maybe she’s right. Maybe I was just covering my ass.”

“I took those bets about who was a worker too,” says Sam. “You were right. It was the only thing we could do to have any leverage.” He sounds more sure than I feel.

“Cassel?” Daneca says. “Wait a second.”

“What?” Her voice sounds so odd—tentative—that I look up.

“She shouldn’t have been able to do that,” Daneca says. “Lila just told you off.”

“You can love someone and still argue with—,” I start to say, and stop myself. Because that’s the difference between real love and cursed love. When you really love someone, you can still see them for who they are. But the curse makes love sickly and simple.

I look in amazement toward the doors Lila walked through. “Do you think she could be—better? Not cursed?”

The hope that blooms inside of me is terrifying.

Maybe. Maybe she could come out of this and not hate me. Maybe she could even forgive me. Maybe.

I cross the quad, heading back to my dorm room, Sam next to me. I’m smiling, despite knowing better. Despite knowing my own luck. I’m dreaming dreams where I’m clever enough to weasel my way out of all my problems. Sucker dreams. The kind of dreams con artists love to exploit.

“So,” Sam says slowly, his voice low. “It’s always like that? When you transform?”

Yesterday morning seems so long ago. I remember Sam’s look of terror as he stared down at me, sprawled on the floor. I can still feel the blowback creeping up my spine. I want to deny any of it happened; in those moments I felt more naked than I ever have in my life. So naked I was turned inside out.

“Yeah,” I say, watching moths circling the dim lights along the path. The moon overhead is just a sliver. “Pretty much. That was worse than usual because I worked myself twice in one night.”

“Where were you?” Sam asks. “What happened?”

I hesitate.

“Cassel,” Sam says. “Just tell me if it’s bad.”

“I was in Lila’s room.”

“Did you break her window?” he asks. I should have realized the story was all over campus. Everyone knows about the rock, about the threat.

“No,” I say. “The person who did that couldn’t have known I was there.”

He looks over sharply, a line appearing over the bridge of his nose, between his eyebrows, as he frowns. “So you know who it was? Who broke the window?”

I nod my head, but I don’t volunteer Audrey’s name. Telling Sam isn’t like telling Northcutt, but I still feel bound to keep the secret.

“When it rains, it pours,” Sam says.

As we head into the building, my phone buzzes in my pocket. I open it against my chin and put it to my ear. “Yeah?”

“Cassel?” Lila says softly.

“Hey,” I say. Sam turns and gives me a knowing look, then keeps walking, leaving me to sit on the steps to the second floor.

“I’m sorry I yelled at you,” she says.

My heart sinks. “You are?”

“I am. I get why you took those bets. I’m not sure I like it, but I get it. I’m not mad.”

“Oh,” I say.

“I guess I just freaked out,” she says. “After last night. I don’t want this to be just pretend.” She’s speaking so quietly now that I can barely make out the words.

“It’s not,” I say. The words feel ripped out of my chest. “It never was.”

“Oh.” She’s quiet for a long moment. Then, when she does speak, I can hear the smile in her voice. “I still expect my winnings, Cassel. You can’t sweet-talk me out of those.”

“Ruthless as usual,” I say, grinning, looking down at the stair. Someone dropped their gum, someone else stepped on it. Now it’s a streak of grimy pink.

I’m such a fool.

“I love you,” I say, because I might as well now, when it no longer matters what I do. I’ve made up my mind. Before she can reply, I close my phone, hanging up on her.

Then I rest my head on the cold iron railing. Maybe the curse would fade eventually, but I will never be sure it’s completely gone. So long as she’s fond of me, I will never know whether it’s forced. Curses are subtle. Sure, emotion work is supposed to wear off, but how can anyone know? I have to be certain, and I never will be.

There never were any good choices.

I call Agent Jones. I’ve lost his card, so I just call the main number for the agency in Trenton. After a couple of transfers, I get an answering machine. I tell him that I need more time, just a couple more days, just until Monday, and then I’ll give him his murderer.

* * *

Once you decide you have to do something, it’s almost a relief. Waiting is harder than doing, even when you hate what you’re about to do.

The longer I look for alternatives, the darker those alternatives get.

I have to accept what is.

I am a bad person.

I’ve done bad things.

And I’m going to keep on doing them until somebody stops me. And who’s going to do that? Lila can’t. Zacharov won’t. There’s only one person who can, and he’s shown himself to be pretty unreliable.

Sam’s up in our room, paging through Othello when I come in. His iPod is plugged into our speakers, and the sound of Deathwerk rattles the windows.

“You okay?” he shouts over the guttural vocals.

“Sam,” I say, “remember how at the beginning of the semester you said you went to that special effects warehouse and cleaned it out? How you were ready for anything.”

“Yeah . . . ,” he says, suspicious.

“I want to frame someone for my brother’s murder.”

“Who?” he asks, turning down the sound. He must be used to me saying crazy things, becaus

e he’s totally serious. “Also, why?”

I take a deep breath.

Framing someone requires several things.

First you have to find a person who makes a believable villain. It helps if she’s already done something bad; it helps even more if some part of what you’re setting her up for is true.

And since she’s done something bad, you don’t have to feel so terrible about picking her to take the fall.

But the final thing you need is for your story to make sense. Lies work when they’re simple. They usually work a lot better than the truth does. The truth is messy. It’s raw and uncomfortable. You can’t blame people for preferring lies.

You especially can’t blame people when that preference benefits you.

“Bethenny Thomas,” I say.

Sam frowns at me. “Wait, what? Who’s that?”

“Dead mobster’s girlfriend. Two big poodles. Runner.” I think of Janssen in the freezer. I hope he’d approve of my choice. “She put out a hit on her boyfriend, so it’s not like she hasn’t murdered someone.”

“And you know that how?” Sam asks.

I’m trying really hard to be honest, but telling the whole thing to Sam seems beyond me. Still, the fragments sound ridiculous on their own. “She said so. In the park.”

He rolls his eyes. “Because the two of you were so friendly.”

“I guess she mistook me for someone else.” I sound so much like Philip that it scares me. I can hear the menace in my tone.

“Who?” Sam asks, not flinching.

I force my voice back to normal. “Uh, the person who killed him.”

“Cassel .” He groans, shaking his head. “No, don’t worry, I’m not going to ask why she would think that. I don’t want to know. Just tell me your plan.”

I sit down on my bed, relieved. I’m not sure I can endure another of my confessions, despite the fact that I have so much yet to confess.

I used to stake out joints for robberies with my dad sometimes, back when I was a kid. See what people’s patterns were. When they left for work. When they returned. If they ate at the same place each night. If they went to bed at the same time. The more tight a schedule, the more tidy a robbery.

What I remember most, though, are the long stretches of sitting in the car with the radio on. The air would get stuffy, but I wasn’t allowed to roll down the windows far enough to get a good breeze. The soda would get stale, and eventually I’d have to piss into a bottle because I wasn’t supposed to get out of the car. There were only two good things about stakeouts. The first thing was that Dad let me pick out anything at the gas station mart that I wanted snack-wise. The second was that Dad taught me how to play cards. Poker. Three-card monte. Slap. Crazy eights.

Sam’s pretty good at games. We spend Friday night watching Bethenny’s apartment building and gambling for cheese curls. We learn that the doorman takes a couple of smoking breaks when no one’s around. He’s a beefy dude who tells off a homeless guy harassing residents for change out front. Bethenny takes her dogs for a run in the evening and walks them twice more before she goes out for the night. At dawn the doormen change shifts. The guy who comes in is skinny. He eats two doughnuts and reads the newspaper before residents start coming downstairs. It’s late Saturday morning by then, and Bethenny’s still not back, so we bag it and go home.

I drop Sam off at his place around eleven and crash for a few hours at the garbage house. I wake up when the cordless phone rings next to my head. I’d forgotten that I brought it into the room days ago. It’s tangled in the sheets.

“Yeah?” I grunt.

“May I speak with Cassel Sharpe?” my mother asks in her chirpiest voice.

“Mom, it’s me.”

“Oh, sweetheart, your voice sounded so funny.” She seems happier than I’ve heard her in a long time. I shove myself into a sitting position.

“I was sleeping. Is everything okay?” My automatic fear is that she’s in trouble. That the Feds have gotten tired of waiting and have picked her up. “Where are you?”

“Everything’s perfect. I missed you, baby.” She laughs. “I’ve just been swept up in so many new things. I met so many nice people.”

“Oh.” I cradle the phone against my shoulder. I should probably feel bad that I suspected her of murder. Instead I feel guilty for not feeling guilty. “Have you seen Barron recently?” I ask. I hope not. I hope she has no idea he’s blackmailing me.

I hear the familiar hiss of a cigarette being lit. She inhales. “Not in a week or two. He said he had a big job coming up. But I want to talk about you. Come see me and meet the governor. There’s a brunch on Sunday that I think you’d just love. You should see the rocks some of the women wear, plus the silverware’s reeeal.” She draws the last part out long, like she’s tempting a dog to a bone.

“Governor Patton? No, thanks. I’d rather eat glass than eat with him.” I carry the phone downstairs and pour out the old coffee in the pot. I dump in new water and fresh grounds. The clock says its three in the afternoon. I have to get moving.

“Oh, don’t be like that,” says Mom.

“How can you sit there while he goes on and on about proposition two? Okay, fine. He’s a really tempting mark. I’d love to see him get conned, but it’s not worth it. Mom, things could get really bad. One mistake and—”

“Your mother doesn’t make mistakes.” I hear her blow out the smoke. “Baby, I know what I’m doing.”

The coffee is dripping, steam rising from the pot. I sit down at the kitchen table. I try not to think about her the way she was when I was a kid, sitting right where I am now, laughing at something Philip said or ruffling my hair. I can almost see my dad, sitting at the table, showing Barron how to flip a quarter over his knuckles while she makes breakfast. I can smell my dad’s cigarillos and the blackening bacon. The back of my eyes hurt.

“I don’t know what I’m doing anymore,” I say. You might think I’m crazy, telling her that. But she’s still my mother.

“What’s wrong, sweetheart?” The concern in her voice is real enough to break my heart.

I can’t tell her. I really can’t. Not about Barron or the Feds or how I thought she was a murderer. Certainly not about Lila. “School,” I say, resting my head in my hands. “I guess I’m getting a little overwhelmed.”

“Baby,” she says in a harsh whisper, “in this world, lots of people will try to grind you down. They need you to be small so they can be big. You let them think whatever they want, but you make sure you get yours. You get yours.”

I hear a man’s voice in the background. I wonder if she’s talking about me at all. “Is someone there?”

“Yes,” she says sweetly. “I hope you’ll think about coming on Sunday. How about I give you the address and you can think about it?”

I pretend to copy down the location of Patton’s stupid brunch. Really I’m just pouring myself a cup of coffee.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

WAKING UP IN THE MIDDLE of the day always leaves you with a slightly dazed feeling, as though you’ve stepped out of time. The light outside the windows is wrong. My body feels heavy as I force it up and into clothing.

I stop at the store for more coffee and a prop, then head over to Daneca’s house. I walk across the green lawn, up to the freshly painted door between two manicured bushes. Everything is as pretty as a picture.

When I ring the bell, Chris answers. “What?” he says. He’s got on a pair of shorts and flip flops with an oversize shirt. It makes him look even younger than he is. There’s a smudge of something blue in his hair.

“Can I come in?”

He pushes the door wide. “I don’t care.”

I sigh and walk past him. The scent of lemon polish fills the hallway, and there’s a girl in the living room running a vacuum. For some reason it never occurred to me that Daneca grew up with maids, but of course she did.

“Is Mrs. Wasserman here?” I ask the girl.

She takes headphones out of her ears

and smiles at me. “What was that?”

“Sorry,” I say. “I was just wondering if you know where Mrs. Wasserman is.”

The girl points. “In her office, I think.”

I walk through the house, past the artwork and the antique silver. I knock on the frame of a glass-paneled door. Mrs. Wasserman opens it, hair pulled up into a makeshift bun with a pencil shoved through her mass of curls. “Cassel?” she says. She’s got on paint-stained sweatpants and is holding a mug of tea.

I hold out the violets I bought at the garden supply store. I don’t know much about flowers, but I liked how velvety they looked. “I wanted to say thanks for the other day. For the advice.”

Gifts are very useful to con men. Gifts create a feeling of debt, an itchy anxiety that the recipient is eager to be rid of by repaying. So eager, in fact, that people will often overpay just to be relieved of it. A single spontaneously given cup of coffee can make a person feel obligated to sit through a lecture on a religion they don’t care about. The gift of a tiny, wilted flower can make the recipient give to a charity they dislike. Gifts place such a heavy burden that even throwing away the gift doesn’t remove the debt. Even if you hate coffee, even if you didn’t want that flower, once you take it, you want to give something back. Most of all, you want to dismiss that obligation.

“Oh, thank you,” Daneca’s mother says. She looks surprised, but pleased. “It was no trouble at all, Cassel. I’m always here if you want to talk.”

“You mean that?” I ask, which is maybe laying it on really thick, but I need to push her a little. This is her chance to repay me. It doesn’t hurt that I know she’s a sucker for hard-luck cases.

“Of course,” she says. “Anything you need, Cassel.”

Bingo.

I like to think it’s the gratitude that makes her over-generous, but I guess I’ll never know. That’s the problem with not trusting people—you never find out if they’d have helped you on their own.

Daneca is on her computer when I come into her room. She looks up at me in surprise.

“Hey,” I say. “Your little brother let me in.” I’m already not being entirely honest by failing to mention I talked with her mother, but I’m determined to do nothing more dishonest than that. I hate myself enough already without conning one of my only friends.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

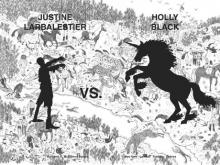

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

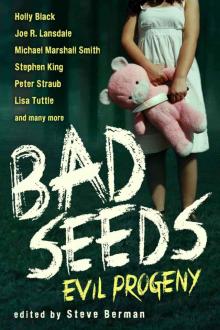

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

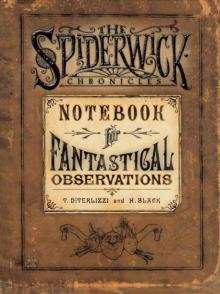

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown