- Home

- Holly Black

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Page 21

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Read online

Page 21

“You okay?” she asked again.

“I’m fine.”

She pulled him closer. His hand came to her thigh, and without conscious intention, he found himself opening her gown, kissing her, her breasts, fuller now than he had ever known them. Her back arched. Her fingers were in his hair.

She whispered, “Gerald, that feels nice.”

He continued to kiss her, his interest rising. The room was dark, but he could see her very clearly in his mind: the Sara he had known, lithe and supple; this new Sara, this strange woman who shared his bed, her beauty rising out of some deep reservoir of calm and peace. He traced the slope of her breasts and belly. Here. And here. He guided her, rolling her to her side, her back to him, rump out-thrust as Exavious had recommended during a particularly awkward and unforgettable consultation—

“No, Gerald,” she said. She said, “No.”

Gerald paused, breathing heavily. Below, in the depths of the darkened house, the furnace shut off, and into the immense silence that followed, he said, “Sara—”

“No,” she said. “No, no.”

Gerald rolled over on his back. He tried to throttle back the frustration rising once more within him, not gone after all, not dissipated, merely … pushed away.

Sara turned to him, she came against him. He could feel the bulk of her belly interposed between them.

“I’m afraid, Gerald. I’m afraid it’ll hurt the baby.”

Her fingers were on his thigh.

“It won’t hurt the baby. Exavious said it won’t hurt the baby. The books said it won’t hurt the baby. Everyone says it won’t hurt the baby.”

Her voice in the darkness: “But what if it does? I’m afraid, Gerald.”

Gerald took a deep breath. He forced himself to speak calmly. “Sara, it won’t hurt the baby. Please.”

She kissed him, her breath hot in his ear. Her fingers worked at him. She whispered, “See? We can do something else.” Pleading now. “We can be close, I want that.”

But Gerald, the anger and frustration boiling out of him in a way he didn’t like, a way he couldn’t control—it scared him—threw back the covers. Stood, and reached for his robe, thinking: Hot. It’s too hot. I’ve got to get out of here. But he could not contain himself. He paused, fingers shaking as he belted the robe, to fling back these words: “I’m not so sure I want to be close, Sara. I’m not at all sure what I want anymore.”

And then, in three quick strides, he was out the door and into the hall, hearing the words she cried after him—“Gerald, please”—but not pausing to listen.

The flagstone floor in the den, chill against his bare feet, cooled him. Standing behind the bar in the airy many-windowed room, he mixed himself a gin and tonic with more gin than tonic and savored the almost physical sense of heat, real and emotional, draining along his tension-knotted spine, through the tight muscles of his legs and feet, into the placid stones beneath.

He took a calming swallow of gin and touched the remote on the bar. The television blared to life in a far corner and he cycled through the channels as he finished his drink. Disjointed, half-glimpsed images flooded the darkened room: thuggish young men entranced by the sinister beat of the city, tanks jolting over desert landscape, the gang at Cheers laughing it up at Cliff’s expense. Poor Cliff. You weren’t supposed to identify with him, but Gerald couldn’t help it. Poor Cliff was just muddling through like anyone—

—Like you, whispered that nasty voice, the voice he could not help but think of as the cockroach.

Gerald shuddered.

On principle, he hated the remote—the worst thing ever to happen to advertising—but now he fingered it again, moved past Letterman’s arrogant smirk. He fished more ice from the freezer, splashed clean-smelling gin in his glass, chased it with tonic. Then, half-empty bottle of liquor and a jug of tonic clutched in one hand, drink and television remote in the other, Gerald crossed the room and lowered himself into the recliner.

His anger had evaporated—quick to come, quick to go, it always had been—but an uneasy tension lingered in its wake. He should go upstairs, apologize—he owed it to Sara—but he could not bring himself to move. A terrific inertia shackled him. He had no desire except to drink gin and thumb through the channels, pausing now and again when something caught his eye, half-clad dancers on MTV, a news story about the unknown cannibal killer in L.A., once the tail-end of a commercial featuring none other than Fenton the giant cockroach himself.

Christ.

Three or four drinks thereafter he must have dozed, for he came to himself suddenly and unpleasantly when a nightmare jolted him awake. He sat up abruptly, his empty glass crashing to the floor. He had a blurred impression of it as it shattered, sending sharp scintillas of brilliance skating across the flagstones as he doubled over, sharp ghosts of pain shooting through him, as something, Christ—

—the cockroach—

—gnawed ravenously at his swollen guts.

He gasped, head reeling with gin. The house brooded over him. Then he felt nothing, the dream pain gone, and when, with reluctant horror, he lifted his clutching hands from his belly, he saw only pale skin between the loosely belted flaps of robe, not the gory mess he had irrationally expected, not the blood—

—so little blood, who would have thought? So little blood and such a little—

No. He wouldn’t think of that now, he wouldn’t think of that at all.

He touched the lever on the recliner, lifting his feet, and reached for the bottle of gin beside the chair. He gazed at the shattered glass and then studied the finger or two of liquor remaining in the bottle; after a moment, he spun loose the cap and tilted the bottle to his lips. Gasoline-harsh gin flooded his mouth. Drunk now, dead drunk, he could feel it and he didn’t care, Gerald stared at the television.

A nature program flickered by, the camera closing on a brown grasshopper making its way through lush undergrowth. He sipped at the gin, searched densely for the remote. Must have slipped into the cushions. He felt around for it, but it became too much of an effort. Hell with it.

The grasshopper continued to progress in disjointed leaps, the camera tracking expertly, and this alone exerted over him a bizarre fascination. How the hell did they film these things anyway? He had a quick amusing image: a near-sighted entomologist and his cameraman tramping through some benighted wilderness, slapping away insects and suffering the indignities of crotch-rot. Ha-ha. He touched the lever again, dropping the footrest, and placed his bare feet on the cool flagstones, mindful in a meticulously drunken way of the broken glass.

Through a background of exotic bird-calls, and the swish of antediluvian vegetation, a cultured masculine voice began to speak: “Less common than in the insect world, biological mimicry, developed by predators and prey through millennia of natural selection is still … ”

Gerald leaned forward, propping his elbows on his knees. A faraway voice whispered in his mind. Natural selection. Sophomore biology had been long ago, but he recognized the term as an element of evolutionary theory. What had Exavious said?

That nasty voice whispering away …

He had a brief flash of the ultrasound video, which Sara had watched again only that evening: the fetus, reptilian, primitive, an eerie wakeful quality to its amniotic slumber.

On the screen, the grasshopper took another leap. Music came up on the soundtrack, slow, minatory, almost subliminal. “ … less commonly used by predators,” the voiceover said, “biological mimicry can be dramatically effective when it is … ” The grasshopper took another leap and plummeted toward a clump of yellow and white flowers. Too fast for Gerald really to see, the flowers exploded into motion. He sat abruptly upright, his heart racing, as prehensile claws flashed out, grasped the stunned insect, and dragged it down. “Take the orchid mantis of the Malaysian rainforest,” the voiceover continued. “Evolution has disguised few predators so completely. Watch again as … ” And now the image began to replay, this time in slow motion, so that Gera

ld could see in agonizing detail the grasshopper’s slow descent, the flower-colored mantis unfolding with deadly and inevitable grace from the heart of the blossom, grasping claws extended. Again. And again. Each time the camera moved in tighter, tighter, until the mantis seemed to fill the screen with an urgency dreadful and inexorable and wholly merciless.

Gerald grasped the bottle of gin and sat back as the narrator continued, speaking now of aphid-farming ants and the lacewing larva. But he had ceased to listen. He tilted the bottle to his lips, thinking again of that reptilian fetus, awash in the womb of the woman he loved and did not want to lose. And now that faraway voice in his mind sounded closer, more distinct. It was the voice of the cockroach, but the words it spoke were those of Dr. Exavious.

Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.

Gerald took a last pull of the bottle of gin. Now what exactly did that mean?

The ball whizzed past in a blur as Gerald stepped up to meet it, his racquet sweeping around too late. He spun and lunged past Lake Conley to catch the ricochet off the back wall, but the ball slipped past, bouncing twice, and slowed to a momentum draining roll.

“Goddamn it!” Gerald flung his racquet hard after the ball and collapsed against the back wall. He drew up his legs and draped his forearms over his knees.

“Game,” Lake said.

“Go to hell.” Gerald closed his eyes, tilted his head against the wall and tried to catch his breath. He could smell his own sweat, tinged with the sour odor of gin. He didn’t open his eyes when Lake slid down beside him.

“Kind of an excessive reaction even for you,” Lake said.

“Stress.”

“Work?”

“That, too.” Gerald gazed at Lake through slitted eyes.

“Ahh.”

They sat quietly, listening to a distant radio blare from the weight-room. From adjoining courts, the squeak of rubber-soled shoes and the intermittent smack of balls came to them, barely audible. Gerald watched, exhaustion settling over him like a gray blanket, while Lake traced invisible patterns on the floor with the edge of his racquet.

“Least I don’t have to worry about the Heather Drug campaign,” Gerald said. Almost immediately, he wished he could pull the words back. Unsay them.

For a long time, Lake didn’t answer. When he did, he said only, “You have a right to be pissed off about that.”

“Not really. Long time since I put a decent campaign together. Julian knows what he’s doing.”

Lake shrugged.

Again, Gerald tilted his head against the wall, closing his eyes. There it was, there it always was anymore, that image swimming in his internal darkness: the baby, blind and primitive and preternaturally aware. He saw it in his dreams; sometimes when he woke he had vague memories of a red fury clawing free of his guts. And sometimes it wasn’t this dream he remembered, but another: looking on, helpless, horrified, while something terrible exploded out of Sara’s smoothly rounded belly.

That one was worse.

That one spoke with the voice of the cockroach. That one said: You’re going to lose her.

Lake was saying, “Not to put too fine a point on it, Gerald, but you look like hell. You come to work smelling like booze half the time, I don’t know what you expect.”

Expect? What did he expect exactly? And what would Lake say if he told him?

Instead, he said, “I’m not sleeping much. Sara doesn’t sleep well. She gets up two, three times a night.”

“So you’re just sucking down a few drinks so you can sleep at night, that right?”

Gerald didn’t answer.

“What’s up with you anyway, Gerald?”

Gerald stared into the darkness behind his closed eyes, the world around him wheeling and vertiginous. He flattened his palms against the cool wooden floor, seeking a tangible link to the world he had known before, the world he had known and lost, he did not know where or how. Seeking to anchor himself to an earth that seemed to be sliding away beneath him. Seeking solace.

“Gerald?”

In his mind, he saw the mantis orchid; on the screen of his eyelids, he watched it unfold with deadly grace and drag down the hapless grasshopper.

He said: “I watch the sonogram tape, you know? I watch it at night when Sara’s sleeping. It doesn’t look like a baby, Lake. It doesn’t look like anything human at all. And I think I’m going to lose her. I think I’m going to lose her, it’s killing her, it’s some kind of … something … I don’t know … it’s going to take her away.”

“Gerald—”

“No. Listen. When I first met Sara, I remember the thing I liked about her—one of the things I liked about her anyway, I liked so much about her, everything—but the thing I remember most was this day when I first met her family. I went home with her from school for a weekend and her whole family—her little sister, her mom, her dad—they were all waiting. They had prepared this elaborate meal and we ate in the dining room, and you knew that they were a family. It was just this quality they had, and it didn’t mean they even liked each other all the time, but they were there for each other. You could feel it, you could breathe it in, like oxygen. That’s what I wanted. That’s what we have together, that’s what I’m afraid of losing. I’m afraid of losing her.”

He was afraid to open his eyes. He could feel tears there. He was afraid to look at Lake, to share his weakness, which he had never shared with anyone but Sara.

Lake said, “But don’t you see, the baby will just draw you closer. Make you even more of a family than you ever were. You’re afraid, Gerald, but it’s just normal anxiety.”

“I don’t think so.”

“The sonogram?” Lake said. “Your crazy thoughts about the sonogram? Everybody thinks that. But everything changes when the baby comes, Gerald. Everything.”

“That’s what I’m afraid of,” Gerald said.

After the gym, Gerald drove for hours without conscious purpose, trusting mindless reflexes to take him where they would. Around him sprawled the city, senseless, stunned like a patient on a table, etherized by winter.

By the time he pulled the Lexus to the broken curb in a residential neighborhood that had been poor two decades past, a few flakes of snow had begun to swirl through the expanding cones of his headlights. Dusk fell out of the December sky. Gerald cracked his window, inhaled cold smoke-stained air, and gazed diagonally across the abandoned street.

Still there. My God, still there after these ten years. A thought recurred to him, an image he had not thought of in all the long months—ages, they felt like—since that first visit to Dr. Exavious: like stepping into icy water, this stepping into the past.

No one lived there anymore. He could see that from the dilapidated state of the house, yard gone to seed, windows broken, paint that had been robin’s egg blue a decade ago weathered now to the dingy shade of mop water. Out front, the wind creaked a realtor’s sign long since scabbed over with rust. The skeletal swing-set remained in the barren yard, and it occurred to him now that his child—his and Sara’s child—might have played there if only …

If only.

Always and forever if only.

The sidewalk, broken and weedy, still wound lazily from the street. The concrete stoop still extruded from the front door like a grotesquely foreshortened tongue. Three stairs still mounted to the door, the railing—Dear God—shattered and dragged away years since.

So short. Three short stairs. So little blood. Who could have known?

He thought of the gym, Lake Conley, the story he had wanted to tell but had not. He had not told anyone. And why should he? No great trauma, there; no abuse or hatred, no fodder for the morning talk shows; just the subtle cruelties, the little twists of steel that made up life.

But always there somehow. Never forgotten. Memories not of this house, though this house had its share, God knows, but of a house very much like this one, in a neighborhood pretty much the same, in another city, in another state, a hundred years in the past or so it

seemed. Another lifetime.

But unforgettable all the same.

Gerald had never known his father, had never seen him except in a single photograph: a merchant mariner, broad-shouldered and handsome, his wind-burned face creased by a broad incongruous smile. Gerald had been born in a different age, before such children became common, in a different world where little boys without fathers were never allowed to forget their absences and loss. His mother, he supposed, had been a good woman in her way—had tried, he knew, and now, looking back with the discerning eye of an adult, he could see how it must have been for her: the thousand slights she had endured, the cruelties visited upon a small-town girl and the bastard son she had gotten in what her innocence mistook for love. Yes. He understood her flight to the city and its anonymity; he understood the countless lovers; now, at last, he understood the drinking when it began in earnest, when her looks had begun to go. Now he saw what she had been seeking. Solace. Only solace.

But forgive?

Now, sitting in his car across the street from the house where his first child had been miscarried, where he had almost lost forever the one woman who had thought him worthy of her love, Gerald remembered.

The little twists of steel, spoken without thought or heat, that made up life.

How old had he been then? Twelve? Thirteen?

Old enough to know, anyway. Old enough to creep into the living room and crouch over his mother as she lay there sobbing, drunken, bruised, a cold wind blowing through the open house where the man, whoever he had been, had left the door to swing open on its hinges after he had beaten her. Old enough to scream into his mother’s whiskey-shattered face: I hate you! I hate you! I hate you!

Old enough to remember her reply: If it wasn’t for you, you little bastard, he never would have left. If it wasn’t for you, he never would have left me.

Old enough to remember, sure.

But old enough to forgive? Not then, Gerald knew. Not now. And maybe never.

They did not go to bed together. Sara came to him in the den, where he sat in the recliner, drinking gin and numbly watching television. He saw her in the doorway that framed the formal living room they never used, and beyond that, in diminishing perspective, the broad open foyer: but Sara foremost, foregrounded and unavoidable.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

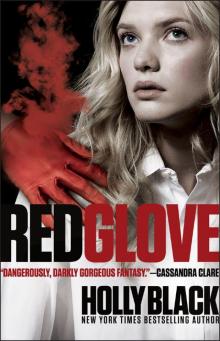

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

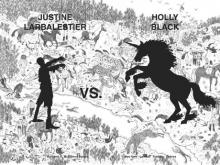

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

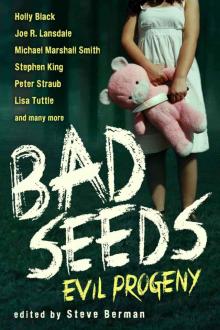

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

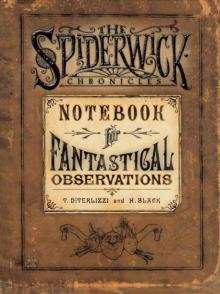

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown