- Home

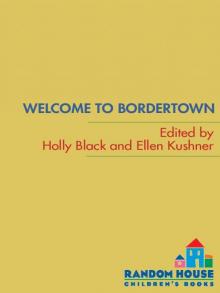

- Holly Black

Welcome to Bordertown Page 3

Welcome to Bordertown Read online

Page 3

“Hi,” she said. She could barely get the words out. “Is that—um, I mean—Do you go to Harvard?”

He stared at her. “How did you— Oh. The shirt.” He looked a little embarrassed. “Yeah, I did. Why?”

* * *

Anush put the lassi down and wiped the yogurt mustache off his lip. The girl with the backpack and the tousled mass of brown curls looked dazzled, enchanted, but not in a good way. He hoped she hadn’t been drinking Mad River water, because those kids never made sense and never shut up.

“That’s where I wanted to go,” she said in that same, breathless voice. “Harvard. In Cambridge, Massachusetts. On the banks of the Charles.”

“Yeah,” Anush said. This was possibly one of the weirdest conversations he’d had yet in Bordertown. “Yeah, that’s right.” How old was she? High school? “Maybe you should apply.”

She was still staring at his chest. He was beginning to get why girls objected to this so strongly. “I did.”

Ouch.

“Hey, it’s okay,” he said lamely. “It’s a really competitive school. Not everyone gets in.”

She sat down at the counter next to him. “That’s why I came here. Anything’s better than staying in Milltown, right? I mean, I love my family, but they don’t understand. They just want me to find a nice guy with a good union job, settle down, make babies and Sunday dinners and—and—”

“And you wanted a nice Harvard boy?” He grinned his most charming grin.

The girl shut up. He watched her face freeze over like he’d just killed her dog or something. Nice going, Anush, he thought. No wonder you can’t get elves to talk to you, either.

“Hey,” he said gently. “I didn’t mean it like that. Of course you wanted a good education. My parents think that’s the most important thing on the planet.”

She kept on twisting her fingers together on the counter.

Boy, he’d really stepped in it this time. “So what other schools did you apply to?” he asked, feeling a little desperate.

“Just Harvard. Everyone knows it’s the best. It’s where I’ve always dreamed of going.”

“But what about your safety school?”

“Safety school? What’s that?”

“You know, the school you know you’ll get into if you don’t get your top pick.”

“You mean the state university? Where I come from, that’s just a party-and-football school. I wanted to go to Harvard and actually learn about things.”

“But there are plenty of good schools besides Harvard,” Anush said patiently. “Didn’t your guidance counselor suggest any others?”

Trish shrugged. “The Milltown school district is broke. We haven’t had a guidance counselor in years.”

“Okay, but—”

“My parents say I can do the two-year course at the community college down the road. But what’s the point? If I’m not good enough for Harvard …”

Anush opened his mouth and shut it again.

“Do you want some coffee?” he asked.

“Tea,” she said stiffly, like she didn’t trust him but was willing to oblige. “I drink herbal tea.”

He nodded over at Cam, held up his cup for another lassi, and started again: “So why Bordertown instead of college?”

“I thought … I thought it would be like in the books,” she muttered to the countertop. “You know—magic. And … and beauty. Like in the olden days, or in a fantasy novel. There’s supposed to be poetry here, and stories, and beautiful elfin music.” She stirred honey into her tea. “But it’s all just gangs and drugs and messed-up kids. Like at home. Just with no parents, and no cops.”

“You haven’t been here long enough to find the beauty, that’s all. There’s a great harper playing this week at The Wheat Sheaf—”

She looked up, her face pale, her eyes bright. “A harper? Like Taliesin, or Thomas the Rhymer?”

She sure knew her Celtic mythology. He risked, “Or Fflewddur Fflam.”

Her eyes glowed like stars. “You’ve read those, too? The Prydain books? By Lloyd Alexander?”

“Of course. I love Taran the Assistant Pig-Keeper, and poor old Gurgi, and Fflewddur with his magic harp. But trust me, Ossian Feldenkranz is no Fflam. He’s a good musician, the real thing. You’ll like his stuff.”

“Which one’s your favorite?”

“I haven’t heard them all yet—”

“No, I mean the Prydain books.” Her face was shining now, her eyes focused, like the smart kid in class she must recently have been. “I used to think The Black Cauldron, but I just reread them this year, and now maybe Taran Wanderer.… Is it true they’re based on Welsh mythology?”

“Oh, yes,” Anush said, “the Mabinogion. I took a whole class on Celtic Myth in Fantastical Literature, and we read that along with Yeats and Synge and Lord Dunsany and Evangeline Walton and R. A. MacAvoy—”

The girl leaned forward. “You can study those? In college?”

“Oh, yeah. My parents weren’t thrilled—they wanted me to do engineering—but I placated them with a double-major in—”

“Tilien!” thrummed a woman’s voice by his ear. “Is that tilien you’re drinking, mortal?” Anush swiveled on his stool to look into eyes the color of violets on the first day of spring. “Here, let me try it.”

The impossibly slender, pale fingers lifted his metal cup, carried it to rose-petal lips that parted like the gates of Paradise to take a sip of his lassi. As she drank, her lashes fanned her cheeks like the peacock feather fans of a prince’s wife.

“Not tilien.” The lassi-scented breath was almost in his own mouth, so close were her lips to his. “What call you this drink, mortal?”

Cam plunked a juice can down in front of the elf goddess. “It’s yogurt lassi made with guanabana. Also known as soursop.”

“Gua-naaaaa-bana.” In her mouth, the word was a poem.

He leaned forward to savor it.

“Very nearly as good. I will taste it again soon.” She smiled at him. “What is your name, mortal man?”

“Anush Gupta.”

“No!” the scruffy girl next to him cried. Maybe her tea had gotten cold.

“Then come, Anush Gupta,” said the Trueblood elf. “Come with me. For we have much to discuss.”

* * *

“Never mind, honey,” said the ponytailed waitress. “He was too old for you, anyway.”

Trish flushed. “It’s not that. I wanted him to tell me about Harvard! And myth classes. And safety schools. And that Welsh thing. Where Prydain comes from.”

“Try Elsewhere Books. Someone there will know.”

“He shouldn’t have told her his real name,” Trish fretted.

“Probably not.”

“Doesn’t it give them power over you?”

“Kiddo, she didn’t need his name for that.” The waitress held out her hand across the counter. “I’m Cam, by the way.”

When Trish saw the tips of her ears, she tried to suppress a gasp.

“It’s cool,” said Cam. “I’m a halfie.”

“I’m, um, Tara.” Trish hadn’t really gotten used to the false name yet. She’d thought about being Eilonwy, but no way did she qualify as the feisty redheaded princess from The Book of Three. And besides, she wasn’t really sure how you pronounced it.

* * *

This is it, Anush thought as he left the Hard Luck Café with the elf—the Trueblood—woman. He was dizzy with desire for her, and as strong as a hundred bulls with the certainty that the courtship rituals of exogamous elves would soon be within his grasp. Sure, a trained anthropologist wasn’t supposed to get data this way, but he felt sure his professor would understand.

He followed her down Ho Street and into a tangle of alleys he didn’t recognize. At a narrow side door, she paused and passed her hand over the latch. It turned from iron to gold. She opened the door and led him up shadowy, uneven stairs and into a room that reminded him of a forest, and of a ship, and of something he’d been prom

ised once and never gotten.

When they lay together at last, peaceful and quiet on a bed of bracken that rustled like silk, she said, “You are beautiful, Anush Gupta. Like the night sky in an autumn wood. Ask me something, and it shall be yours.”

Anush sighed deeply. He thought of asking for a notebook, but that might be blowing his big chance. Instead he said, “I do have a few questions, actually.”

She was fine with the first three. She didn’t mind discussing Trueblood hierarchy or scarcity or isolationist self-segregation. Even the relative ages of mate selection just made her laugh. But when he got to “And how many sexual partners would you say you have in a year?” the woman reared up over his head, her hair falling like frozen water around them both.

“The counting of favors is a cruel thing, Anush Gupta. As well count the breaths it takes to speak your name, or the hopes that bring a hart to the well.”

“I’m sorry,” he said hastily. “We can skip this one if you want.”

“Like skipping stones over a lake? But words are not stones, mortal man. Once spoken, they cannot be sunk below waves.”

“Really”—he tried to catch her eyes, as he had when they were making love—“I said I was sorry.”

She turned away from him huffily. “I should have heeded my mother. She said mortals all were thus. I thought you were different.”

“But I am!” He was actually on his knees. “I am different. I’m not like all the rest—”

He was almost weeping with frustration. Because it was true. He was. Always. Everywhere. Different. He was the Indian kid who loved Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. He was the American kid who loved his mom’s spicy bhelpuri. He was the dutiful son who studied the wrong subject. He was the serious scholar who studied imaginary beings. He was different as could be. Trying to defend himself to an elf was just about the last straw in a lifetime, a haystack, of them.

“Different, are you?” she said coldly. “Then different you shall be.” She raised her hands, began to speak, and stopped. “But wait, my night traveler. I have not wearied of you yet. You and your questions. Clearly we both have much to learn. And your skin is like a river that runs deep and swift after a storm in the mountain. So I give you this choice: whether you shall be different by day or different by night. Choose one, that I may enjoy you the other.”

“Day or—?” he choked, but she said, “So be it. Roam freely in the day, rude as you will, in a form that rudeness allows—but at night, you are mine: all your pleasures, and your questions, and your beauty, all for me.”

“Wait,” protested Anush, “I know this story! It’s kind of the Beastly Bride, and kind of Thomas the Rhymer—with a little Stith Thompson folklore motif number tw— Ouch! Wait a minute, what are you d—”

And that was the last thing he was able to say for a while.

* * *

Trish went to The Wheat Sheaf that night. The place was crowded with all kinds of people—elf, human, even halfies. The other girls at Carterhaugh had told her to steer clear of elves, that they were clannish and mean and ran with dangerous gangs, but everyone here seemed to get along all right. She sat quietly in a corner with a glass of ginger beer and waited for the music to start. Osheen somebody, the Harvard guy had said. A harper. A minstrel. Like in the books.

He didn’t look like the books. He was just a guy with scruffy hippie hair and jeans. But when he lifted the harp and played, the room went still.

I will give my love an apple

Without e’er a core

I will give my love a house

Without e’er a door

I will build my love a palace

Wherein she may be

And she may unlock it

Without e’er a key

Trish let herself live in the music. She was a lady now, sitting in her high hall, her greyhound at her feet while the minstrel played for her and her court.

How can there be an apple

Without e’er a core

How can there be a house

Without—

There was a soft rustling as everyone turned to stare at the striking couple who had just come in: a glorious lady with hair like moonlight and a dress as gold as the sun, and at her side, a dark prince—

Anush. The Harvard guy. Dressed now in a skintight shirt that showed off his well-made chest. He had his arm around the lady and was nuzzling her neck in that stupid, boys-in-the-halls-between-classes way, paying no attention to anyone or anything around them.

Trish looked away. Bad enough that they’d just made her miss the last verse of the Riddle Song, which ended with a flourish and applause. Now she’d never know the answers.

Ossian Feldenkranz stood up, setting the harp aside, and shook out his arms. “And now,” he announced, “I’d like to invite up to the stage a buddy of mine, a landsman from the old country—and a great musician: Yidl Mitn Fidl!”

From the back of the room, a short, scrawny guy with wiry arms and a little goatee came leaping up onto the small stage, brandishing a violin in one hand and a bow in the other. “Hey-upp!” he shouted, or something like that, and the music exploded into a dance tune. It sounded a little like that Polka Variety music her uncle Al liked, and a little like she’d always imagined gypsies would be: wild and happy and sad, all at once. Her feet beat time on the floor. She wished she knew some steps so she could dance.

Some of the people did. Chairs were pushed back. Kids were forming a circle, joining hands, dancing and stamping to the music. Their heads were thrown back, they looked so happy—she realized she was happy, too, just watching. It was like being at the seashore with the sun shining down and the waves beating time.

The music slowed and changed. People drifted back to their seats. The violin played soft now, and slow. Gentle.

“By the hearth, a fire is burning,” Ossian murmured over the fiddle’s tune. “An old rebbe, a learned man, is teaching the children to read: ‘Learn, children,’ he says; ‘don’t be afraid. Every beginning is hard.’ ”

He started singing in a strange language. Yidl closed his eyes, fiddled and swayed. She looked across to where the Harvard guy sat with the elf lady. He was staring at the musicians, longing on his dark face.

What distant land had his people come from, and how had he gotten to go to Harvard? He knew all about books and fantasy and college. Trish wanted to know what he knew.

Learn, children; don’t be afraid. Every beginning is hard, Ossian sang in the language she didn’t know yet.

She went over to the table where the dark prince sat with his elfin lady. “Hi,” Trish said.

He looked at her blankly, like he’d never seen her before.

“I met you yesterday,” she said bravely. “At the café?”

He looked confused. Enchanted? The elf lady was ignoring her completely. Snotty bitch.

“You’re Anush, right?”

“Yes.” His face cleared a little. “I’m Anush.”

“I’m Tara,” Trish said. He frowned. “Like Taran? In the Prydain books? Only a girl?” Anush smiled at her with beautiful white teeth. “So I was wondering,” Trish went on. “I mean, I just wanted to ask you—”

“Anush Gupta,” said the beautiful lady, placing her long white hand on his, “can you arrange cold beer for me at this table?”

Anush started to rise, then paused, his head turned toward the door, where some kind of commotion was erupting. The music fell silent.

The Wheat Sheaf was supposed to be neutral territory, but everyone tensed, looking around the room to see who was elf, who was human, in case they needed to take sides.

A girl burst into the center of the room.

“Oh my god!” she shrieked. “Oh my fucking god! It’s The Wheat Sheaf. It really, really is, just like the Wiki said!”

She had arrow-straight hair and a short straight dress. The guy with her was wearing thick black glasses and huge baggy pants. They looked like something out of a cartoon, which in Bordertown was saying a lot. Ev

eryone stared.

“Dude! We made it!” shouted the guy. “We’re in fucking Bordertown! Get out your iPhone, quick, see if you can still tweet—”

“It’s back!” the girl yelled. “Bordertown’s really back! We made it!”

* * *

The day that my sister’s postcard comes, I make the decision to go and find her; the day after that my bag is packed and I’m ready to head for the Border.

I know what people say: that Bordertown doesn’t exist, that it’s just a myth, a hoax, a mass delusion. Or else, if it does exist, then the road from here to there has long been closed. Or else, if the Way is open, then it’s a road not meant for a guy like me, with dirt under my fingernails and a duffel bag full of tools, not fairy-tale books.

But the Border is real, and I know I’m going to find it. Why? Because I know how to find it. You would, too, if you’d been thinking about it every damn day for thirteen years. My parents never talked about Bordertown—the entire subject of Trish was pretty much off-limits—but that didn’t stop me from searching for every tiny scrap of information I could find: a newspaper mention of the elfin trade here, a radio reference to Border music there; the Bordertown websites that flicker on and off the Internet, semivisible, like ghosts; the Borderland Wikipedia page, which keeps writing and rewriting itself—sensible one moment, gibberish the next, the information constantly changing.

I’m not smart like Trish. I never finished high school, and although I’ve read all of the books she left behind, I read them mostly to keep her spirit close—I’ve never been a dreamer like my sister. I fix things. Cars, appliances, electronics. I can make just about any damn thing run. I’m the kind of guy who needs to take things apart just to figure out how they work, and I tend to think most things in life can be fixed if you have time enough, and patience.

I wanted to know how the Borderlands worked, this place that had swallowed my sister up … so, bit by bit, I gathered information. Bit by bit, I figured out a thing or two. That’s how I know about the semisecret website where The Tough Guide to Bordertown can be downloaded. That’s how I know to prepare my truck by knotting red ribbons on the door handles and scattering the floor with leaves of oak and ash. That’s how I know to burn cedar and sage, fill my pockets with salt, stick a feather behind my ear. Now that the moon is up, I must start the journey before the owl cries twice. (You think I’m making this up? I’m not. It’s a kind of science, just not the kind we’re used to.) Once I get out on the interstate, I’ll head north (or south, it doesn’t matter) and crank up the radio and just keep driving. Eventually the truck will fail, and after that I’ll hitch a ride or walk that last stretch through the Nevernever.…

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

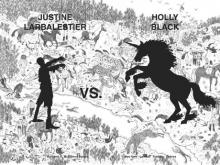

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

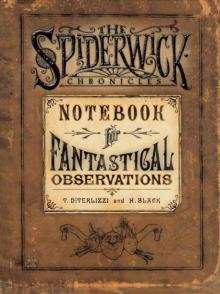

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

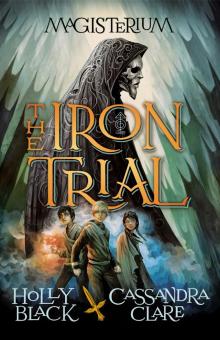

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown