- Home

- Holly Black

Welcome to Bordertown Page 30

Welcome to Bordertown Read online

Page 30

One of us has to get there, I thought, and it had better be me. So I was right, and the girl did me one last favor. She fed me.

She was sweet. I mean honestly, she was sweet. Sometimes I feel bad about her.

Several days later, a rickety camel-drawn omnibus rumbled up a dry gulch and pulled up beside me. There was a board nailed to the front with “Bordertown” spray-painted on it, and other kids were inside. On the back clung a sticker that said “My Mirage Is Smarter Than Your Honor Student.” The driver, who didn’t seem old enough to be driving anything, including a team of camels, asked for a fare. “A trade is fine,” he said, and eyed the duffel bag I carried. I gave him a lolcat T-shirt, size extra-large. He looked puzzled but well pleased.

That girl was smart. You can use T-shirts for money in Bordertown. The elves like band T-shirts, even if they have never heard of the band, and the human kids like to wear weird slogans, even if they have no idea what they mean. T-shirts clothed me, got me into clubs, and helped pay my rent in a boarding house for a month, until I found a place of my own. Those out-of-date T-shirts kept me going for a while in many ways. There’s something hilarious about a Highborn elf in a Jonas Brothers shirt.

If that girl was right about the T-shirts, I thought, maybe she was right about elf blood, too. The essence of life was exactly what I needed. So I made a plan: I would lay low for a while, then jump an elf, drink the magic in his blood, be cured, and go back to the World before anyone caught me; and maybe it would be like years later, and no one would be looking for me there either.

That was before I knew that (a) I liked it here, (b) elves are people, too, and (c) elfin magic can be scary.

So far, I hadn’t had the nerve to mug an elf for his blood. Elves looked strong, and they didn’t respond to my faltering powers of mesmerism like some humans did if caught off guard; elves would fight. Also, it was too hard to tell which ones had magic and how well they could use it. What if I ended up with a curse on me even worse than the one I already had? Anyway, I liked them, even though they were often snobs. I loved the way they looked, and the way they moved, and the way they spoke. I didn’t know how much elf blood I would need to cure myself. It would be awful if I had to take it all. I’ll wait, I thought. I’ll wait, and if I am very lucky, an elf will fall in love with me. I’ll tell him my sad story, and he will sacrifice his blood to me—or get all his friends to pitch in. Okay, that last bit was dumb, but it was more appealing than a hit-or-miss scuffle in a back alley and would do until I thought of another plan. Meanwhile, I would try very, very hard not to kill anyone.

* * *

The bouncer at the door to The Dancing Ferret surprised me. I’d seen her around—her black Mohawk was hard to miss. Laura, I think her name was. She waved away my hand when I offered to pay the cover. “You’re that street artist, aren’t you?” she said. “Locals get in free.”

Wow! I thought. Someone recognized me. I’m a local. Cool!

The owner, Farrel Din, gave me a weird look and shook his head as I passed the booth where he sat, and a surge of anger sank my high. What did that fat elf know about me? Nothing! Who was he to judge? I’m not a poseur! I wanted to yell at him. I’m not trying to look part elf—I’m undead, you asshole! But perhaps he was only annoyed because he knew I didn’t buy drinks. Maybe I should buy one since they had let me in free. I stashed my backpack under a corner table on the outskirts of the room, then maneuvered through the motley patrons to buy a Hobby Horse home brew at the bar. In Bordertown, there is no drinking age. As long as you look like you’re past puberty and you don’t act crazy, you’re okay. I hurried back to my table to protect my goods, but the only person nearby was an elf kid a few tables over, reading a book by the light of a Puck’s Brown Ale sign that someone had defaced to say the obvious. He was reading an actual book, not a Stick Wizard comic or anything like that. Why would you come to a club to read?

“Lambton Wyrm” proclaimed the name on the drum kit. Elves played bass, drums, and guitar, and a skinny human played everything from bagpipes to the bodhran, judging by what lay around him. Either they were new or they sucked, because the room was barely half full.

Sky was even more beautiful than I had first thought, if that was possible. His silver hair shimmered against an icy blue shirt, and his silver and blue guitar matched. Could I make him fall in love with me? I wondered. Could I make my fantasy come true?

The singer, a muscular, bearded human with a fierce grin, took the mic. “Haway, we’re gonna start with this canny song we stole our name from,” he said in a dialect I didn’t know. “It’s an ald song from where I grew up.”

You find out a lot about old music in Bordertown.

He sang with only a pipe as accompaniment at first.

Whisht lads, had yer gobs

And I’ll tell yers ahll an ahful story

Whisht lads, had yer gobs

And I’ll tell yer boot the warm.

As the story unfolded, I discovered that “warm” meant “worm,” in the sense of a whacking great dragon, and more and more instruments joined in until the thrashing crescendo of a thundering fight and a tragic mistake. I was convinced that it would be my favorite of their songs—until they rollicked into “Cushie Butterfield”:

She’s a big lass, she’s a bonnie lass

And she likes her beer

And they call her Cushie Butterfield

And I wish she were here.

I wished I were loud and jolly and likable like Cushie, who was obviously not a skinny, ethereal elfin maiden but who had songs written about her nevertheless. I raised my brew proudly, then caught the reader elf looking at me and put my glass down again with a thump, feeling foolish.

I wanted to go up and talk to Sky between sets, but every time I tried to stand up, my heart lodged in my throat and I could only watch as he talked with other girls, accepted drinks from admirers, and traded elegant insults with his bandmates. I took far too long to work up the nerve, but at last he stood by himself next to the stage, examining a crumpled playlist, and I left my seat to approach him. He half smiled as I walked up, as if he had already forgotten me and was too polite to turn away. I was about to remind him, despite the knot in my gut, but the bass player emerged from a back room to whisper urgently in his ear. Sky turned from me abruptly, climbed onto the stage, and slung his guitar strap over his head. He began to tune his guitar as if I had ceased to exist. I hurried back to my seat, head down, mortified, hoping no one had seen the snub.

I wasn’t ready to give up yet, though. Sky was too beautiful, too tempting. He was full of the magical Faerie blood that could restore what I had lost, all wrapped up in the nicest package I had ever seen. I’d heard the phrase “cold as elf blood,” but in my imagination, his blood was warm and comforting.

If I stay until after closing, maybe they’ll let me help them pack up, I thought. If I was helpful, they might like me and I’d have a chance to get to know Sky better. So when the harsh overhead lights came on and changed the smoky exotic club into a dirty drippy room, I leaned into the corner and made myself seem invisible—I can do that. After the last drunk stumbled into the street, I relaxed, but as soon as I did, a diminutive server with a frown larger than she was marched up to me. “What part of ‘last call’ do you not understand?” she demanded, tossing her fuchsia ponytail.

“It’s okay. She’s with me,” said a scratchy voice. Both the girl and I swiveled our heads in surprise to find Reader Elf had joined us.

The girl snorted in disbelief, but she left.

“How do you rate?” I asked.

He laughed. “Not ‘thank you’?” He sat in the empty chair next to me.

“Yeah, sure. Thank you,” I answered, abashed, but not too much so.

He laid his book on the table: The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins. I think my mother had watched that on Masterpiece Mysteries. It was all Victorian or something. Weird.

“I’m with the band,” he said.

“Oh?” I

found myself warming to him. “In what way?”

“I help recharge the amps and things like that,” he answered, and made a face. “The guitarist is my brother.”

“Sky?” I’m afraid my voice squeaked.

He nodded.

No way, I thought as I looked him up and down.

I didn’t think elves could appear ordinary, but he was the drabbest elf I had ever seen. He looked to be about my age, but he could have been much older, of course. He wore stiff new jeans and a white short-sleeved dress shirt. All he needed was a pocket protector. I noticed that his dandelion fluff of flaxen hair had a pale green tint. Pond scum, I thought, and giggled. I couldn’t tell if that was his real color or a subtle dye. One of his pointy ears had a weird little kink.

“What’s so funny?” he said, but he didn’t look annoyed.

I shrugged. Maybe he’d introduce me to his brother if I was nice to him.

“My name’s Moss. What’s yours?” he asked.

I had no clue what to say. I had had many names out in the World, but here in Bordertown, no one called me anything. Once upon a time, I had been Elizabeth Mary Washington. In the city, Dr. Vee had called me Little Bit, but after I ran away from him, people called me Bloody Mary. That never felt like me, though. That was someone in a story.

“Lizzie,” I told him. It sounded friendly, like “Cushie.”

He chuckled. “What, no fancy Bordertown nickname?”

“Nicknames are given by other people,” I said.

“Not around here.”

“Well, they are in the World,” I said, “and they’re usually not nice.” I didn’t tell him my sister called me Beastie and the kids at school called me Lizard. Yeah, they weren’t friendly nicknames. I glanced over at where the band was packing up their equipment. Wasn’t Moss going to help them? Wasn’t he going to invite me to join in?

“Where do you live?” he asked.

I hesitated. “Down by the South Wall,” I answered vaguely. “You?”

“What does that mean?” Moss asked. He pointed at my shirt and ignored my question—the nerve.

I wore a T that said “YR PWND, DUDE.”

“That means ‘I’m better than you,’ ” I snapped, then heard how arrogant I sounded.

He looked at me blankly. “In what language?”

“Mistyped English.” I spent time trying to explain computer gaming to make up for my rudeness. He loved the whole idea, although I wasn’t sure he understood clearly.

“You’re new in Bordertown, aren’t you?” I said, because even the people who grew up here have some knowledge of the World, if only along the lines of a bad Wikipedia entry.

Moss blushed a tender shell pink.

“Why did you come?” I asked. “I mean, you lived in a magical place, so why come here?”

“Adventure,” he said.

I raised my eyebrows and pointedly examined the dingy bar.

“Well, Bordertown is different anyway,” he said, “and there are no endless lessons.”

“School?” I asked, ready to be sympathetic.

“Sort of.” That’s as much as I got from him on that subject.

“But you had to give up magic that worked all the time.”

“And you had to give up computers.”

I scowled. “There were reasons.”

“Yeah,” he agreed. “There were reasons.”

We both fell silent.

“Why did you help me?” I asked after a while.

“You’re interesting,” he said. “You might be my adventure.”

I burst out laughing—the best laugh I’d had in a long time. The boy might be plain but he sure had the elfin tongue.

That’s when I noticed the band had left, and Moss noticed, too.

He cried out an unintelligible word and jumped to his feet. “The band’s at Sluggo’s tomorrow night,” he told me. “Ginger and Green Lady Lane. See you there?”

“Uh, yeah!” I answered as he ran for the back door.

“And drink your beer next time,” he called over his shoulder, “because I’m buying.”

Outside, I passed the alley that ran behind The Ferret. A loaded cart attached to a put-putting trike sat ignored. The band surrounded Moss and seemed to be giving him a hard time. It must suck to be the kid brother, I thought, especially when all your brother’s friends get in the act, too. As if he felt my eyes, Moss looked over at me. I waved and left him to his fate. I had business at the docks.

I ate down by the river often. There were scavengers there who were too messed up on river water to say no to me, and if they ever remembered what happened, no one would believe them anyway. When I’d first arrived, I wondered if the Mad River tasted like blood, but I didn’t try it. The water made the kids who drank it taste funny, though, and I had to force myself. Maybe that’s why the last two had made me throw up. Polite elves say to their host, “I ate quite well. I’ll now be sick.” That wasn’t meant to be literal. Luckily, I kept down enough blood not to starve. If it got worse, though, I’d have to find another source of food, and I didn’t even want to think of the danger that entailed.

I rounded up my dinner with no trouble, but I couldn’t find the right angle or something. My teeth wouldn’t slide in smoothly; I had to try several times. I made a mess of his neck.

After I ate and threw up, I cried.

Even without Dr. Vee’s final bite, I would be exactly like him, forever and ever, and I wouldn’t even be good at it, and I would never, never, never find a way to stop.

When I finished crying, I wiped my face with my sleeve and headed home.

I had found myself a nice little squat on a cobbled, dead-end road not far from Hell’s Gate. Ma always said I would go to hell. I guess she was right. But hell was a long walk away, and streetlights were rare—I was thankful I could see well in the dark.

The Old Town was crowded when you were up on Ho Street, but there were many ruined places scattered through the Old Town where no one came anymore. For a few blocks, I passed occupied houses. I liked to peek through the windows at the cozy rooms hung with bright fabrics and lit by spell lamps draped with patterned scarves. Farther south on Hell Street, the houses looked gap-toothed and hollow-eyed, with vacant windows and broken-in doors. More and more empty lots with broken fences lined the road, and after them sat a burned-out gas station where fuel was a memory. The sign had once read “Shell,” but someone had managed to shatter the “S.” I wondered if that was how the road got its name.

The night became all indigo and purple shadows, and the outlines of roadside trees rose like torn construction paper layers, ragged against the moony sky. I had to be careful of roots that pushed up through the paving stones. As I passed a squat deco apartment building, I thought I heard footfalls behind me. I flattened against the wall and peered back through the darkness. Nothing.

I had been happy when I first got to Bordertown—relaxed for the first time in ages—but lately I’d felt a growing unease. It prickled on my neck at night and squirmed in my stomach. The feeling had been worse the last two weeks.

I had read there were catchers in Bordertown—people who dragged runaways back to the World—but I had left home a long time ago. How would my parents know I came here, and would they care? No, it was Dr. Vee I thought of every time something skittered in the shadows or a darker silhouette moved against the night. He didn’t take kindly to ungrateful kids.

Halfway home, I took a detour through Damnation Alley over to South Street. I needed a few more sketchpads. Just my luck, some Packers were hanging out by the stone-pillared entrance of South Street School. This was no place to be mistaken for someone part elf. I dashed across the street, cut though a corner parking lot, ran down the side road, dodged around the back of a rusted Camry, and climbed through the torn chain-link fence behind the school. As I approached an open window, a shower of pebbles clattered against the cracked windowpanes.

I turned. A gangbanger stood behind me, but he took off

running in the direction of the Camry. What the …? I didn’t wait to figure him out; I slipped through the window of the boys’ bathroom.

Inside, I ran down the corridor and took the stairs up to the second floor. My footsteps echoed. The peeling, graffiti-covered walls made my fingers itch to add my own tag—but I wasn’t Bloody Mary anymore, was I?

I trotted past the cobwebbed classrooms. Next to the media center, carpeted with mildewed books, was the art room. On one of my previous expeditions, I had found a cupboard in there, behind a jumble of dented file cabinets and the shards of a desk. No one had been curious enough to clear the debris away, but pickings were slim, and so I did. Jackpot! Inside sat stacks of sketchpads filled with yellow-edged sheets of paper. There were also pencils, brushes, dried and cracked poster paint, charcoal, grease pencils, and construction paper that was hidden from the light, so the colors were still bright. But the prize was a set of Prismacolor pencils and pastels. I had carefully barricaded the door again, loaded what I could in a black-smutted curtain, and hefted my treasure back home.

Tonight I had to huff and heave to move those file cabinets out of the way. I felt certain the work had been easier last time. After I grabbed three sketchpads, I decided to move only one file cabinet back in place. You’re becoming a wuss, I told myself as I ran down the steps at the other end of the corridor that led to the gym. I negotiated the piles of volleyball nets, punctured basketballs, and ancient beer cans, and let myself out the door on the south side of the school, where the buses used to pick up the kids. I guessed a lot of those buses were now down in the trailer parks, past my place, substituting for caravans.

I lived near the South Wall, as if I had barely squeezed inside Bordertown and possibly still didn’t belong. My place sat on the presciently named Woodland Road, where the crumbling brick houses squatted like wild animals among feral garden foliage, their roofs covered with the fur of lichens, trees sprouting from attic dormers like horns. The abandoned dwellings looked as if, when they had evolved enough, they would shamble out into the Never-never to find new nomad lives. In the light of one predawn, I had been sure I’d seen fruit on the branches at the back of my house, but when I climbed over the wall to check, I couldn’t find any.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

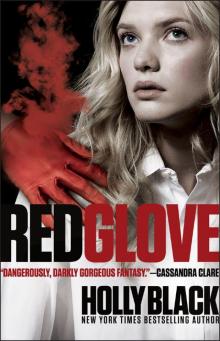

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

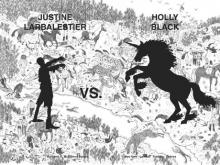

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

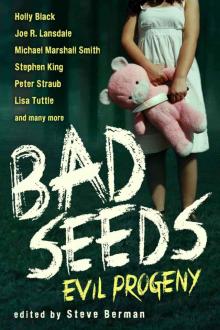

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

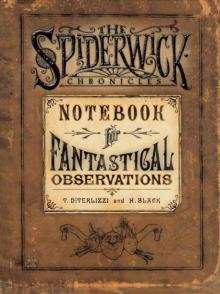

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

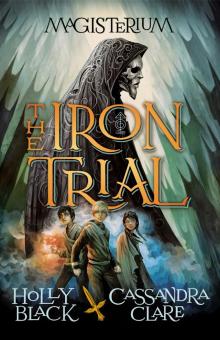

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown