- Home

- Holly Black

The Modern Faerie Tales Page 34

The Modern Faerie Tales Read online

Page 34

The Tom above her sighed with what she thought might be relief and his hands moved under her shirt. “I knew you were lonely.”

“I wasn’t lonely,” Val said automatically, pulling back. She didn’t know if she was lying or not. Had she been lonely? She thought of faeries and their inability to lie and wondered what they did when they didn’t know what the truth was.

At her thought of faeries, Tom’s skin turned green, his hair blackened and fell around his shoulders until it was Ravus she saw, Ravus’s long fingers that touched her skin and his hot eyes staring down at her.

She found herself frozen, repulsed by her own fascination. The tilt of his head was just right, his expression inquiring.

“You don’t want me,” she said, but whether she was speaking to the image of Ravus in front of her or to Dave, she wasn’t sure.

He pressed his mouth against hers and she felt the sting of his teeth against her lip and she shuddered with desire and with dread.

How could she not have known she wanted this, when now she wanted nothing else? She knew it wasn’t really Ravus and that it was obscene to pretend it was, but she let him ease her jeans off her hips anyway. Her heart thudded against her chest, as though she’d been running, as though she was in some danger, but she reached up her arms and threaded her fingers through oil-black hair. His long body settled over hers and she gripped the muscles of his back, focusing on the hollow of his throat, the glittering gold of his slitted eyes, as she tried to ignore Dave’s grunts. It was almost enough.

The next afternoon, as Ravus put Val through a series of sword moves holding the wooden blade, she watched his closed, remote face and despaired. Before, she had been able to convince herself that she didn’t feel any way about him, but now she felt as if she’d had a taste of food that left her starving for a banquet that would never come.

Walking back from the bridge, she passed near where the Dragon Bus let off. Three hookers shivered in their short skirts. One girl in a faux ponyskin coat walked toward Val with a smile, then turned away as though she realized Val wasn’t a boy.

At the next block, she crossed the street to avoid a bearded man in a miniskirt and floppy boots with their laces undone. Steam rose from under his skirt as he urinated on the sidewalk.

Val picked her way through the streets to the entrance to the tunnel platform. As she got close to the concrete park, she saw Lolli arguing with a girl wearing a monster-fur coat with a spiky rubber backpack over it. For a moment, Val felt an odd sense of disorientation. The girl was familiar, but so totally out of context that Val couldn’t place her.

Lolli looked up. The girl turned and followed Lolli’s glance. Her mouth opened in surprise. She started toward Val on platform boots, a sack of flour clutched in her arm. It was only when Val noticed someone had painted a face on the flour that she realized she was looking at Ruth.

“Val?” Ruth’s arm twitched up like she was going to reach for Val, but then thought better of it. “Wow. Your hair. You should have told me you were going to cut it off. I would have helped you.”

“How did you find me?” Val asked numbly.

“Your friend,” Ruth looked back at Lolli skeptically. “She answered your phone.”

Val reached automatically for her bag, even knowing that her phone must not be inside of it. “I turned it off.”

“I know. I tried to call you a zillion times and your voice mail is full. I’ve been freaking out.”

Val nodded, at a loss as to what to say. She was conscious of the ground-in dirt on her pants, the black half-moons of her fingernails and the stink of her body, the smells that scrubbing in public restrooms with your clothes mostly on didn’t really make better.

“Listen,” Ruth said. “I brought someone to meet you.” She held out the sack of flour. It had eyes outlined with heavy black liner and a tiny, pursed mouth shaded with glittering blue nail polish. “Our baby. You know, it’s hard on him with one of his mommies gone and it’s hard on me, being a single parent. In Health class, I had to do all the worksheets alone.” Ruth gave Val a wobbly smile. “I’m sorry I was such an asshole. I should have told you about Tom. I started to, like a million times. I just never got the words all of the way out.”

“It doesn’t matter anymore,” Val said. “I don’t care about Tom.”

“Look,” said Ruth. “It’s freezing. Can we go inside? I saw a bubble tea place not too far from here.”

Was it freezing? Val was so used to being cold when she wasn’t using Never that it seemed normal for her fingers to be numb and her marrow to feel like it was made from ice. “Okay,” she said.

Lolli had a smug expression on her face. She lit a cigarette and blew twin streams of white smoke from her nostrils. “I’ll tell Dave you’ll be back soon. I don’t want him to worry about his new girlfriend.”

“What?” For a moment, Val didn’t know what she meant. Sleeping with Dave seemed so unreal, something done in the middle of the night, drunk with glamour and sleep.

“He says you two made it last night.” Lolli sounded haughty, but Dave obviously hadn’t told her that Val had looked like Lolli when she’d done it. It filled Val with a shameful relief.

Now Val understood why Ruth was here, why Lolli had lifted her cell phone and set up this scene. She was punishing Val.

Val guessed it was just about what she deserved. “It’s no big deal. It was just something to do.” Val paused. “He was just trying to make you jealous.”

Lolli looked surprised and then suddenly, awkward. “I just didn’t think you liked him like that.”

Val shrugged. “Be back in a while.”

“Who is she?” Ruth asked as they walked toward the bubble tea place.

“Lolli,” Val said. “She’s okay, mostly. I’m crashing with her and some of her friends.”

Ruth nodded. “You could come home, you know. You could stay with me.”

“I don’t think that your mom would be down with that.” Val opened the wood and glass door and stepped into the smell of sugary milk. They sat at a table in the back, balancing on the small rosewood boxes the place had for seats. Ruth thrummed her fingers on the glass top of the table as though her nerves had settled into her skin.

The waitress came and they ordered black pearl tea, toast with condensed milk and coconut butter, and spring rolls. She stared at Val for a long moment before she left their table, as if evaluating whether or not they could pay.

Val took a deep breath and resisted the urge to bite the skin around her finger. “It’s so weird that you’re here.”

“You look sick,” Ruth said. “You’re too skinny and your eyes are one big bruise.”

“I—”

The waitress set their things down on the table, forestalling whatever Val had been about to say. Glad for the distraction, Val poked at her drink with the fat, blue straw, and then sucked up a large, sticky tapioca and a mouthful of sweet tea. Everything Val did seemed slow, her limbs so heavy that chewing on the tapioca felt exhausting.

“I know you’re going to say that you’re fine,” Ruth said. “Just tell me that you really don’t hate me.”

Val felt something inside her waver and then she finally was able to start to explain. “I’m not mad at you anymore. I feel like such a sucker, though, and my mother . . . I just can’t go back. At least not yet. Don’t try to talk me into it.”

“When then?” Ruth asked. “Where are you staying?”

Val just shook her head, putting another piece of toast in her mouth. They seemed to melt on her tongue, gone before she realized she’d eaten them all. At another table, a group of glitter-covered girls exploded in laughter. Two Indonesian men looked over at them, annoyed.

“So what did you name the kid?” Val asked.

“What?”

“Our flour baby. The one I ran off on without even paying child support.”

Ruth grinned. “Sebastian. Like it?”

Val nodded.

“Well, here’s someth

ing that you probably won’t like,” Ruth said. “I’m not going home unless you come with me.”

No matter what Val said, she couldn’t talk Ruth into leaving. Finally, thinking that seeing the actual squat might convince her, Val brought her down to the abandoned platform. With someone else there, Val noticed anew the stink of the place, sweat and urine and burnt-sugar Never, the animal bones on the track and the mounds of clothes that never got moved because they were crawling with bugs. Lolli had her kit unrolled and was shaking some Never onto a spoon. Dave was already soaring, the smoke from his cigarette forming the shapes of cartoon characters that chased each other with hammers.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” Luis said. “Let me guess. Another stray cat for Lolli to shove off onto the tracks.”

“V-Val?” Ruth’s voice trembled as she looked around.

“This is my best friend, Ruth,” Val said before she realized how juvenile that sounded. “She came looking for me.”

“I thought we were your best friends.” Dave smiled a smile that was half-leer and Val regretted letting him touch her, letting him think he had some power over her.

“We’re all best friends,” Lolli said, shooting him a glare as she rested one of her leg’s on Luis’s, her boot nearly touching his crotch. “All the bestest of friends.”

Dave’s face crumpled.

“If you were any kind of friend to her, you wouldn’t drag her into this shit,” Luis told Val, twisting away from Lolli.

“How many people are down here? Come out where I can see you,” a gruff voice called.

Two policemen walked down the stairs. Lolli froze, the spoon in her hand still over the fire. The drug started to blacken and burn. Dave laughed, a weird crazy laugh that went on and on.

Flashlights cut through the dim station. Lolli dropped her spoon, grown too hot to hold, and the beams converged on her, then moved to blind Val. She shaded her eyes with her hand.

“All of you.” One of the cops was a woman, her face stern. “Stand against the wall, hands on your head.”

One beam caught Luis and the male cop nudged him with his boot. “Go. Let’s go. We heard some reports there were kids down here, but I didn’t believe it.”

Val stood slowly and walked to the wall, Ruth beside her. She felt so sick with guilt that she wanted to vomit. “I’m sorry,” she whispered.

Dave just stood stock still in the middle of the platform. He was shaking.

“Something wrong?” the female cop shouted, making it not at all a question. “Against the wall!” With that, her speech turned to barking. Where she had stood was a black dog, larger than a Rottweiler, with foam running from its mouth.

“What the hell?” The other cop turned, pulled out his gun. “That your dog? Call it off.”

“It’s not our dog,” Dave said with an eerie smile.

The dog turned toward Dave, growling and barking. Dave just laughed.

“Masollino?” the policeman yelled. “Masollino?”

“Stop fucking around,” Luis called. “Dave, what are you doing?”

Ruth dropped her arms from her head. “What’s going on?”

The dog’s teeth were bright as it advanced against the policeman. He pointed the gun at it and the dog stopped. It whined and he hesitated. “Where’s my partner?”

Lolli giggled and the man looked up sharply, then quickly back at the dog.

Val took a step forward, Ruth still holding her arm so tight that it hurt. “Dave,” she hissed. “Come on. Let’s go.”

“Dave!” Luis yelled. “Turn her back!”

The dog moved at that, turning and leaping toward where they stood, lolling tongue a slash of red in the dark.

Two sharp pops were followed by silence. Val opened her eyes, not even aware she had closed them. Ruth screamed.

Lying on the ground was the female cop, bleeding from her neck and side. The other officer stared in horror at his own gun. Val froze, too stunned to move, her feet like lead. Her mind was still groping for a solution, some way to undo what had been done. This is just an illusion, she told herself. Dave is playing a joke on all of us.

Lolli jumped down into the well of the tracks and took off, gravel crunching under her boots. Luis grabbed Dave’s arm and pulled him toward the tunnels. “We have to get out of here,” he said.

The police officer looked up as Val leaped off the side of the platform, Ruth behind her. Luis and Dave were already disappearing into the darkness.

A shot rang out behind them. Val didn’t look back. She ran along the track, clutching Ruth’s hand like they were little kids crossing the road. Ruth squeezed twice, but Val could hear her start to sob.

“Cops never understand anything,” Dave said as they moved through the tunnels. “They got all these quotas about arresting people and that’s all they care about. They found our place and they were just going to lock it up so nobody could ever use it and where’s the sense in that? We’re not hurting anyone by being down there. It’s our place. We found it.”

“What are you talking about?” Luis said. “What were you thinking back there? Are you bug-fuck crazy?”

“It’s not my fault,” Dave said. “It’s not your fault. It’s not anybody’s fault.”

Val wished he would shut up.

“That’s right,” Luis said, his voice shaking. “It’s nobody’s fault.”

They emerged in the Canal Street station, hopping on the platform and getting on the first train that stopped. The car was mostly empty, but they stood anyway, braced against the door as the train swayed along.

Ruth had stopped crying, but her makeup made dark smudges on her cheeks and her nose was red. Dave seemed emptied of all emotion, his eyes not meeting anyone else’s. Val couldn’t imagine what he was feeling at that moment. She wasn’t even sure how to name what she felt.

“We can crash in the park tonight,” Luis said. “Dave and I did that before we found the tunnel.”

“I’m going to take Ruth to Penn Station,” Val said suddenly. She thought of the policewoman, the memory of her death like a weight that got heavier with each step away from the corpse. She didn’t want Ruth dragged down with the rest of them.

Luis nodded. “And you’re going with her?”

Val hesitated.

“I’m not getting on that train alone,” Ruth said fiercely.

“There’s someone I have to say good-bye to,” Val said. “I can’t just disappear.”

They got off at the next stop, transferred to an uptown train and rode to Penn Station, then walked upstairs to check the times. Afterward they settled in the Amtrak waiting area, and Lolli bought coffee and soup that none of them touched.

“Meet me here in an hour,” Ruth said. “The train leaves fifteen minutes after that. You can say good-bye to this guy in that time, right?”

“If I’m not back, you have to get on the train,” Val said. “Promise me.”

Ruth nodded, her face pale. “So long as you promise to be back.”

“We’re going to be by the weather castle in Central Park,” Lolli said. “If you miss your train.”

“I’m not going to miss it,” Val said, glancing at Ruth.

Lolli swirled a spoon into a tub of soup, but didn’t raise it to her mouth. “I know. I’m just saying.”

Val stumbled out into the cold, glad to be away from them all.

When she got to the bridge, it was still light enough to see the East River, brown as coffee left too long on the burner. Her head hurt and the muscles in her arms spasmed and she realized that she hadn’t had a dose of Never since the evening before.

Never more than two days in a row. She couldn’t remember when that rule had been forgotten and the new rule had become every day and sometimes more than that.

Val knocked on the stump and slipped inside the bridge, but despite the threat of daylight, Ravus was gone. She considered finger painting a message on a torn grocery flier, but she was so tired that she decided to wait a little while

longer. Sitting down in the club chair, the scents of old paper, leather, and fruit lulled her into leaning back her head and parting the curtain just slightly. She sat for an oblivious hour, watching the sun dip lower, setting the sky aflame, but Ravus didn’t return and she only felt worse. Her muscles, which had ached like they did after exercise, now burned like a charley horse that woke you from sleep.

She looked through his bottles and potions and mixtures, careless of what she disturbed and where things were moved, but she found not a single granule of Never to take away the pain.

A family was finishing their picnic on the rocks as Val shuffled into Central Park, the mother packing up leftover sandwiches, a lanky daughter pushing one of her brothers. The two boys were twins, Val noticed. She’d always found twins sort of creepy, as though only one of them could be the real one. The father glanced at Val, but his eyes rested on a cyclist’s long, bare legs as he slowly chewed his food.

Val walked on, legs aching, past a lake thick with algae, where a riderless boat floated along in the dimming light. An older couple strolled by the bank, arm in arm, as a jogger in spandex huffed his way around them, MP3 player bobbing against his biceps. Normal people with normal problems.

The path continued over a courtyard whose walls were carved with berries and birds, vines so intricate they nearly looked alive, blooming roses, and less familiar flowers.

Val stopped to lean against a tree, its roots exposed and tangled like the pattern of veins under her skin, the pewter bark of the trunk, wet and dark with frozen sap. She’d been walking for a while, but there was no castle in sight.

Three boys with low-slung pants passed, one bouncing a basketball off his friend’s back.

“Where’s the weather castle?” she called.

One boy shook his head. “No such thing.”

“She means Belvedere Castle,” said the other, pointing his hand at an angle, halfway back in the direction she’d come from. “Over the bridge and through the Ramble.”

Val nodded. Over the bridge and through the woods. Everything hurt, but she kept going, anticipating the sting of the needle and the sweet relief it would bring. She thought back to Lolli sitting by the fire with the spoon in her hand and her breath stopped at the thought that all the Never was still back there, in the tunnels, with the dead woman, then hated herself that that was what she worried about, that that was what stopped her breath.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

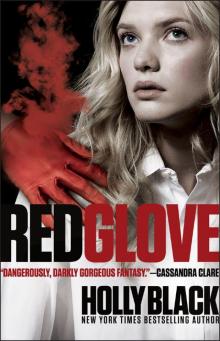

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

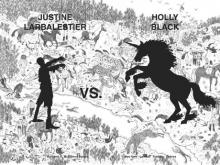

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

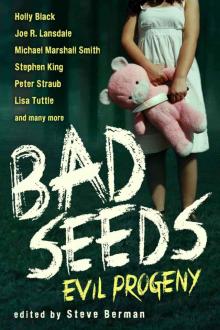

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

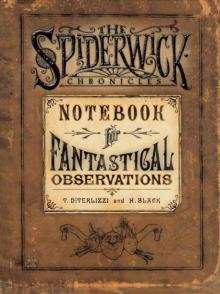

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

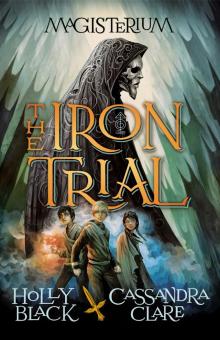

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

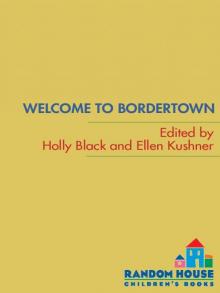

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown