- Home

- Holly Black

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Page 4

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Read online

Page 4

From one extreme to another, thought Marilyn. The story of my life.

Only a year ago she and Derek, still newly married, were making comfortable plans to have a child—perhaps two—“someday.”

Then Joan—Derek’s ex-wife—had decided she’d had her fill of mothering, and almost before Marilyn had time to think about it, she’d found herself with a half-grown daughter.

And following quickly on that event—while Marilyn and Kelly were still wary of each other—Derek’s widowed sister had died, leaving her four children in Derek’s care.

Five children! Perhaps they wouldn’t have seemed like such a herd if they had come in typical fashion, one at a time with a proper interval between.

It was the children, too, who had made living in New York City seem impossible. This house had been in Derek’s family since it was built, but no one had lived in it for years. It had been used from time to time as a vacation home, but the land had nothing to recommend it to vacationers: no lakes or mountains, and the weather was unusually unpleasant. It was inhospitable country, a neglected corner of New York state.

It should have been a perfect place for writing—their friends all said so. An old house, walls soaked in history, set in a brooding, rocky landscape, beneath an unlittered sky, far from the distractions and noise of the city. But Derek could write anywhere—he carried his own atmosphere with him, a part of his ingrained discipline—and Marilyn needed the bars, restaurants, museums, shops and libraries of a large city to fill in the hours when words could not be commanded.

The silence was suddenly too much to bear. Derek wasn’t typing—he might be wanting conversation. Marilyn walked down the long dark hallway—thinking to herself that this house needed more light fixtures, as well as pictures on the walls and rugs on the cold wooden floors.

Derek was sitting behind the big parson’s table that was his desk, cleaning one of his sixty-seven pipes. The worn but richly patterned rug on the floor, the glow of lamplight and the books which lined the walls made this room, the library and Derek’s office, seem warmer and more comfortable than the rest of the house.

“Talk?” said Marilyn, standing with her hand on the doorknob.

“Sure, come on in. I was just stuck on how to get the chief slave into bed with the mistress of the plantation without making her yet another clichéd nymphomaniac.”

“Have him comfort her in time of need,” Marilyn said. She closed the door on the dark hallway. “He just happens to be on hand when she gets a letter informing her of her dear brother’s death. In grief, and as an affirmation of life, she and the slave tumble into bed together.”

“Pretty good,” Derek said. “You got a problem I can help you with?”

“Not a literary one,” she said, crossing the room to his side. Derek put an arm around her. “I was just wondering if we shouldn’t get a horse for Kelly. I was out to look at the barn. It’s all boarded and locked up, but I’m sure we could get in and fix it up. And I don’t think it could cost that much to keep a horse or two.”

“Or two,” he echoed. He cocked his head and gave her a sly look. “You sure you want to start using a barn with a rather grim history?”

“What do you mean?

“Didn’t I ever tell you the story of how my, hmmm, great-uncle, I guess he must have been—my great-uncle Martin, how he died?”

Marilyn shook her head, her expression suspicious.

“It’s a pretty gruesome story.”

“Derek … ”

“It’s true, I promise you. Well … remember my first slave novel?”

“How could I forget. It paid for our honeymoon.”

“Remember the part where the evil boss-man who tortures his slaves and horses alike is finally killed by a crazed stallion?”

Marilyn grimaced. “Yeah. A bit much, I thought. Horses aren’t carnivorous.”

“I got the idea for that scene from my great-uncle Martin’s death. His horses—and he kept a whole stable—went crazy, apparently. I don’t know if they actually ate him, but he was pretty chewed up when someone found his body.” Derek shifted in his chair. “Martin wasn’t known to be a cruel man. He didn’t abuse his horses; he loved them. He didn’t love Indians, though, and the story was that the stables were built on ground sacred to the Indians, who put a curse on Martin or his horses in retaliation.”

Marilyn shook her head. “Some story. When did all this happen?”

“Around 1880.”

“And the barn has been boarded up ever since?”

“I guess so. I remember the few times Anna and I came out here as kids we could never find a way to get inside. We made up stories about the ghosts of the mad horses still being inside the barn. But because they were ghosts, they couldn’t be held by normal walls, and roamed around at night. I can remember nights when we’d huddle together, certain we heard their ghosts neighing … ” His eyes looked faraway. Remembering how much he had loved his sister, Marilyn felt guilty about her reluctance to take in Anna’s children. After all, they were all Derek had left of his sister.

“So this place is haunted,” she said, trying to joke. Her voice came out uneasy, however.

“Not the house,” said Derek quickly. “Old Uncle Martin died in the barn.”

“What about your ancestors who lived here before that? Didn’t the Indian curse touch them?”

“Well … ”

“Derek,” she said warningly.

“OK. Straight dope. The first family, the first bunch of Hoskins who settled here were done in by the Indians. The parents and the two bond-servants were slaughtered, and the children were stolen. The house was burned to the ground. That wasn’t this house, obviously.”

“But it stands on the same ground.”

“Not exactly. That house stood on the other side of the barn—though I doubt the present barn stood then—Anna and I used to play around the foundations. I found a knife there once, and she found a little tin box which held ashes and a pewter ring.”

“But you never found any ghosts.”

Derek looked up at her. “Do ghosts hang around once their house is burned?”

“Maybe.”

“No, we never did. Those Hoskins were too far back in time to bother with, maybe. We never saw any Indian ghosts, either.”

“Did you ever see the ghost horses?”

“See them?” He looked thoughtful. “I don’t remember. We might have. Funny what you can forget about childhood. No matter how important it seems to you as a child … ”

“We become different people when we grow up,” Marilyn said.

Derek gazed into space a moment, then roused himself to gesture at the wall of books behind him. “If you’re interested in the family history, that little set in dark green leather was written by one of my uncles and published by a vanity press. He traces the Hoskinses back to Shakespeare’s time, if I recall. The longest I ever spent out here until now was one rainy summer when I was about twelve … it seemed like forever … and I read most of the books in the house, including those.”

“I’d like to read them.”

“Go ahead.” He watched her cross the room and wheel the library ladder into position. “Why, are you thinking of writing a novel about my family?”

“No. I’m just curious to discover what perversity made your ancestor decide to build a house here, or all godforsaken places on the continent.”

Marilyn thought of Jane Eyre as she settled into the window seat, the heavy green curtains falling back into place to shield her from the room. She glanced out at the chilly gray land and picked up the first volume.

James Hoskins won a parcel of land in upstate New York in a card game. Marilyn imagined his disappointment when he set eyes on his prize, but he was a stubborn man and frequently unlucky at cards. This land might not be much but it was his own. He brought his family and household goods to a roughly built wooden house. A more permanent house, larger and built of native rock, would be built in time.

> But James Hoskins would never see it built. In a letter to relatives in Philadelphia, Hoskins related:

“The land I have won is of great value, at least to a poor, wandering remnant of Indians. Two braves came to the house yesterday, and my dear wife was nearly in tears at their tales of powerful magic and vengeful spirits inhabiting this land.

“Go, they said, for this is a great spirit, as old as the rocks, and your God cannot protect you. This land is not good for people of any race. A spirit (whose name may not be pronounced) set his mark upon this land when the earth was still new. This land is cursed—and more of the same, on and on until I lost patience with them and told them to be off before I made powerful magic with my old Betsy.

“Tho’ my wife trembled, my little daughter proved fiercer than her Ma, swearing she would chop up that old pagan spirit and have it for her supper—which made me roar with laughter, and the Indians to shake their heads as they hurried away.”

Marilyn wondered what had happened to that fierce little girl. Had the Indians stolen her, admiring her spirit?

She read on about the deaths of the unbelieving Hoskinses. Not only had the Indians set fire to the hasty wooden house; they had first butchered the inhabitants.

“They were disemboweled and torn apart, ripped by knives in the most hungry, savage, inhuman manner, and all for the sin of living on land sacred to a nameless spirit.”

Marilyn thought of the knife Derek said he’d found as a child.

Something slapped the window. Marilyn’s head jerked up, and she stared out the window. It had begun to rain, and a rising wind slung small fists of rain at the glass.

She stared out at the landscape, shrouded now by the driving rain, and wondered why this desolate rocky land should be thought of as sacred. Her mind moved vaguely to thought of books on anthropology which might help, perhaps works on Indians of the region which might tell her more. The library in Janeville wouldn’t have much—she had been there, and it wasn’t much more than a small room full of historical novels and geology texts—but the librarian might be able to get books from other libraries around the state, perhaps one of the university libraries …

She glanced at her watch, realizing that school had let out long before; the children might be waiting at the bus stop now, in this terrible weather. She pushed aside the heavy green curtains.

“Derek—”

But the room was empty. He had already gone for the children, she thought with relief. He certainly did better at this job of being a parent than she did.

Of course, Kelly was his child; he’d had years to adjust to fatherhood. She wondered if he would buy a horse for Kelly and hoped that he wouldn’t.

Perhaps it was silly to be worried about ancient Indian curses and to fear that a long-ago even would be repeated, but Marilyn didn’t want horses in a barn where horses had once gone mad. There were no Indians here now, and no horses. Perhaps they would be safe.

Marilyn glanced down at the books still piled beside her, thinking of looking up the section about the horses. But she recoiled uneasily from the thought. Derek had already told her the story; she could check the facts later, when she was not alone in the house.

She got up. She would go and busy herself in the kitchen, and have hot chocolate and cinnamon toast waiting for the children.

The scream still rang in her ears and vibrated through her body. Marilyn lay still, breathing shallowly, and stared at the ceiling. What had she been dreaming?

It came again, muffled by distance, but as chilling as a blade of ice. It wasn’t a dream; someone, not so very far away, was screaming.

Marilyn visualized the house on a map, trying to tell herself it had been nothing, the cry of some bird. No one could be out there, miles from everything, screaming; it didn’t make sense. And Derek was still sleeping, undisturbed. She thought about waking him, then repressed the thought as unworthy and sat up. She’d better check on the children, just in case it was one of them crying out of a nightmare. She did not go to the window; there would be nothing to see, she told herself.

Marilyn found Kelly out of bed, her arms wrapped around herself as she stared out the window.

“What’s the matter?”

Kelly didn’t shift her gaze. “I heard a horse,” she said softly. “I heard it neighing. It woke me up.”

“A horse?”

“It must be wild. If I can catch it and tame it, can I keep it?” Now she looked around, her eyes bright in the moonlight.

“I don’t think … ”

“Please?”

“Kelly, you were probably just dreaming.”

“I heard it. It woke me up. I heard it again. I’m not imagining things,” she said tightly.

“Then it was probably a horse belonging to one of the farmers around here.”

“I don’t think it belongs to anyone.”

Marilyn was suddenly aware of how tired she was. Her body ached. She didn’t want to argue with Kelly. Perhaps there had been a horse—a neigh could sound like a scream, she thought.

“Go back to bed, Kelly. You have to go to school in the morning. You can’t do anything about the horse now.”

“I’m going to look for it, though,” Kelly said, getting back into bed. “I’m going to find it.”

“Later.”

As long as she was up, Marilyn thought as she stepped out into the hall, she would check on the other children, to be sure they were all sleeping.

To her surprise, they were all awake. They turned sleepy, bewildered eyes on her when she came in and murmured broken fragments of their dreams as she kissed them each in turn.

Derek woke as she climbed in beside him. “Where were you?” he asked. He twitched. “Christ, your feet are like ice!”

“Kelly was awake. She thought she heard a horse neighing.”

“I told you,” Derek said with sleepy smugness. “That’s our ghost horse, back again.”

The sky was heavy with the threat of snow; the day was cold and too still. Marilyn stood up from her typewriter in disgust and went downstairs. The house was silent except for the distant chatter of Derek’s typewriter.

“Where are the kids?” she asked from the doorway.

Derek gave her a distracted look, his hands still poised over the keys. “I think they all went out to clean up the barn.”

“But the barn is closed—it’s locked.”

“Mmmm.”

Marilyn sighed and left him. She felt weighted by the chores of supervision. If only the children could go to school every day, where they would be safe and out of her jurisdiction. She thought of how easily they could be hurt or die, their small bodies broken. So many dangers, she thought, getting her coral-colored coat out of the front closet. How did people cope with the tremendous responsibility of other lives under their protection? It was an impossible task.

The children had mobilized into a small but diligent army, marching in and out of the barn with their arms full of hay, boards or tools. Marilyn looked for Kelly, who was standing just inside the big double doors and directing operations.

“The doors were chained shut,” she said, confused. “How did you—”

“I cut it apart,” Kelly said. There was a hacksaw in the toolroom.” She gave Marilyn a sidelong glance. “Daddy said we could take any tools from there that we needed.”

Marilyn looked at her with uneasy respect, then glanced away to where the other chilren were working grimly with hands and hammers at the boards nailed across the stall doors. The darkness of the barn was relieved by a storm lantern hanging from a hook.

“Somebody really locked this place up good,” Kelly said. “Do you know why?”

Marilyn hesitated, then decided. “I suppose it was boarded up so tightly because of the way one of your early relatives died here.”

Kelly’s face tensed with interest. “Died? How? Was he murdered?”

“Not exactly. His horses killed him. They … turned on him one night, nobody every knew why.”<

br />

Kelly’s eyes were knowing. “He must have been an awful man, then. Terribly cruel. Because horses will put up with almost anything. He must have done something so—”

“No. He wasn’t supposed to have been a cruel man.”

“Maybe not to people.”

“Some people thought his death was due to an Indian curse. The land here was supposed to be sacred; they thought this was the spirit’s way of taking revenge.”

Kelly laughed. “That’s some excuse. Look, I got to get to work, OK?”

Marilyn dreamed she went out one night to saddle a horse. The barn was filled with them, all her horses, her pride and delight. She reached up to bridle one, a sorrel gelding, and suddenly felt—with disbelief that staved off the pain—powerful teeth bite down on her arm. She heard the bone crunch, saw the flesh tear, and then the blood …

She looked up in horror, into eyes which were reddened and strange.

A sudden blow threw her forward, and she landed face-down in dust and straw. She could not breathe. Another horse, her gentle black mare, had kicked her in the back. She felt a wrenching, tearing pain in her leg: when finally she could move she turned her head and saw the great yellow teeth, stained with her blood, of both her horses as they fed upon her. And the other horses, all around her, were kicking at their stalls. The wood splintered and gave, and they all came to join in the feast.

The children came clattering in at lunchtime, tracking snow and mud across the redbrick floor. It had been snowing since morning, but the children were oblivious to it. They did not, as Marilyn had expected, rush out shrieking to play in the snow but went instead to the barn, as they did every weekend now. It was almost ready, they said.

Kelly slipped into her chair and powdered her soup with salt. “Wait will you see what we found,” she said breathlessly.

“Animal, vegetable, or mineral?” Derek asked.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

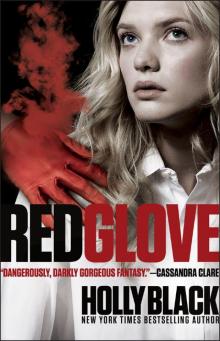

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

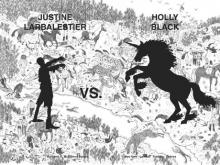

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

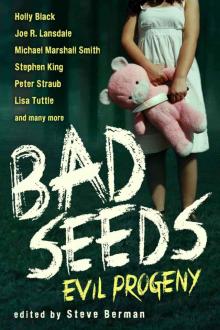

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

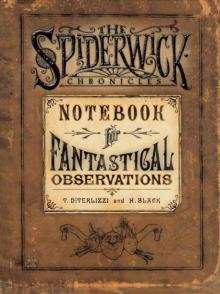

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

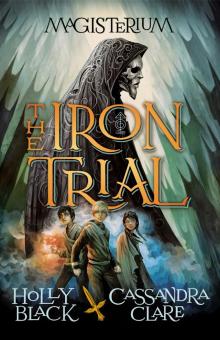

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown