- Home

- Holly Black

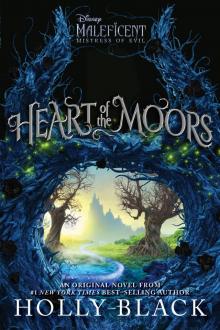

Heart of the Moors Page 4

Heart of the Moors Read online

Page 4

Three soldiers chased him down, one tackling him into the dirt. Then the other two grabbed the man by his arms and forced him up to his knees.

“A poacher,” said Lord Ortolan with disgust. “Hunting on the queen’s lands, no less.”

Lady Fiora was huddled with a few of the other young women, their horses drawn into a knot. They looked a little frightened, and Aurora began to realize that they expected her to punish the man on the spot.

“Your Majesty,” he said, clutching the rabbits in his hands anxiously, “please. My family is hungry. The yield on our farm was poor this year and my wife is very sick.”

A man-at-arms hit him in the side with his pole arm. “Silence.”

Another pulled the rabbits from his hands.

The farmer looked down and spoke no more. He was visibly trembling.

“What punishment does he expect?” Aurora asked Prince Phillip. For the man to be so afraid, it must be very bad indeed.

Lord Ortolan pushed his way to the front, clearly glad to be of use. He spoke before Phillip could. “Blinding would be considered merciful.”

Aurora was astonished.

“Have him sewn into the skin of a deer and we will set our dogs on him,” said one of the men-at-arms. “That’s what your grandfather King Henry would have done.” A few of the others laughed.

The man began to weep and beg incoherently.

Were these the same humans who thought the faeries of the Moors were monsters? Did they not see how horrible it was to have so much and not be willing to give anything to someone in need?

Aurora bent down near the farmer. “What is your name?” she asked.

“Hammond, Your Majesty,” he managed to get out through his tears. “Oh, please…”

She hated the idea of hunting, but Hammond was no more cruel than any fox or owl or other animal that killed to feed its young—and she could no more justify punishing him than one of them. He was only trying to survive. Nobles killed far more than they could eat and had to justify nothing.

“You may take rabbits from my woods so long as your family needs food, Hammond,” she said.

She turned to the soldiers and drew herself up. This time when she spoke, she didn’t hide her anger or her horror at their treatment of the man. “Give him back the rabbits he caught and let him go.”

No soldier hesitated to obey her.

“Surely there must be some punishment,” Lord Ortolan sputtered, “or peasants will take advantage of you. Your woods will be picked clean.”

Aurora wanted to contradict him, but it was probably true that no rules around hunting on royal land would result in the forest being emptied, and not necessarily by those in need. “I hereby decree that from now forward, any citizen of Perceforest may take one single rabbit from the queen’s woods without punishment. Furthermore, anyone who is hungry may come to the palace and be given a ration of barley for every member of their family.”

“The royal treasury cannot possibly sustain that,” Lord Ortolan said in a quelling manner.

“If the people are fed, they won’t have to steal. And they can pay their taxes.” If the treasury could afford to pay for all the confections that were set before the nobles, it could afford grain for families in difficulty, Aurora thought. “Furthermore, I proclaim that no one, under any circumstances, shall blind another person or sew them into a deerskin and set dogs on them. Is that understood?”

Hammond bowed over and over again. “Bless you, Your Majesty. You are kindness itself.” Then, stumbling over his own feet, with his rabbits once more clutched tight against his chest, he started back toward the village.

The entire hunting party was silent. Aurora was sure they thought she’d made a terrible mistake, but she regretted none of it.

Then Lady Fiora shrieked.

Aurora spun around.

“What are those?” Count Alain demanded, pointing.

Three wallerbogs stood on a fallen tree, blinking at the human riding party with wide, expressive eyes and snuffling with their trunk-like snouts. The mischievous faeries must have heard the commotion and crept over from the Moors.

They were the size of human toddlers, with frog-like bodies and enormous ears that stuck out from their heads.

“Wallerbogs,” Aurora said. “They don’t mean any—”

“They’re hideous!” said Lady Fiora.

Giggling, one of them chucked a fistful of mud at the girl. It struck her right in the side of her head, spattering across her face. Aurora sucked in a breath.

Prince Phillip covered his mouth. One of the other courtiers began to laugh. It was contagious, spreading to the rest. Only Lord Ortolan was grim-faced.

And Count Alain, whose eyes narrowed.

The wallerbogs pointed, laughing so hard that one of them fell over.

“You’ve given offense to my sister and I will have satisfaction,” Count Alain shouted, riding toward them.

With shouts of glee, the wallerbogs scattered, heading back toward the Moors, their frog-like bodies half hopping.

Count Alain kicked his heels into the sides of his mount, sending his horse galloping hard after them.

“Stop!” Aurora shouted. She ran to Nettle and swung herself onto her horse’s back. “Do not follow them into the Moors!”

“I will not stand an insult like that to my sister,” he shouted back.

“Don’t be a fool,” Prince Phillip called out.

She could tell the moment Count Alain crossed into the Moors. He passed one of the enormous stones that marked the boundary, and it seemed as though he dropped into smoke, briefly disappearing from view. When he rode out the other end of the fog, he had an arrow notched in his bow. He trained it on one of the retreating wallerbogs.

Then he let the arrow fly.

One of the large vine-covered trees moved. It towered twenty feet in the air, looming over Count Alain. It had enormous mossy horns of bark and a face like a skull made of wood. A tree sentry, a guardian of the Moors.

The sentry backhanded Count Alain off his horse, sending him flying into one of the shallow pools.

The humans behind Aurora screamed.

The tree man lifted Count Alain into the air. Count Alain’s legs kicked wildly.

“No!” Aurora shouted, sliding off her horse and running toward them. She was the queen of the Moors as much as she was the queen of Perceforest. Maleficent had put the crown on her head, and the faeries had to listen to her commands as surely as her human subjects did. “Let him go!”

Too late, she realized her mistake.

The sentry heard her, and its fingers opened immediately, letting Count Alain fall.

Now Aurora was screaming.

Wings beating at the air and mouth curved in a bright, malicious smile, Maleficent caught Count Alain and held him high above the hunting party.

She looked as terrifying as any legend and twice as beautiful.

Diaval, in raven form, circled above her head. He let out a caw.

“Is this yours?” Maleficent asked Aurora. “You seem to have misplaced it.”

“Put me down!” Count Alain shouted, ignoring how she’d saved him from a nasty fall.

“Please,” Lady Fiora said, taking Aurora’s arm, “my brother was only protecting me.”

“That creature attacked first,” Lord Ortolan protested.

“The wallerbog?” Prince Phillip asked incredulously.

Lord Ortolan went on. “You saw it. My queen, you must order your—your godmother to put him down.”

“Human,” Maleficent said to Count Alain, her fangs flashing as she spoke, “you shot an arrow in the Moors. There was a time I would have crushed your skull for such an offense. I would have put a curse on you so that if you ever shot another, it would come back and strike you through the heart.”

Aurora hated it when her godmother talked about curses. But Alain seemed to realize finally that he was in danger.

“Your pardon, my queen,” he said, gritting h

is teeth. “And your pardon, too, winged lady. Fiora is my only sister, and I am overly protective of her.”

“Put him down,” Aurora said. “Please.”

Maleficent swooped low, making the hunting party cry out in surprise. Then she dropped Count Alain, sending him tumbling a short distance into the ferns and vines of the wood. He looked wet, miserable, and furious.

Aurora had thought it would be a simple thing to make peace between the humans and the faeries. She thought it was only a matter of making them see that they were wrong about each other. But thinking of Simon’s family and seeing the look on Count Alain’s face, she was no longer sure that the peace her treaty promised was possible.

Nor was she certain anyone wanted it.

“Go back to the castle,” Aurora told the hunting party.

“Surely you don’t mean to remain in the woods alone,” said Lord Ortolan.

She looked up at the winged figure hovering above them. “No, not alone.”

Aurora was nearly her height, Maleficent noted as they made their way through the Moors. She remembered the tiny flaxen-haired child who had grabbed hold of both of her horns and refused to let go.

The willful girl who had giggled at her scowls.

Who had transmuted her anger into love.

But Aurora was not smiling now.

“Tell me about this wall of flowers,” she said, hands on her hips. “Spiky flowers. Did you think I wouldn’t find out?”

Maleficent gestured airily. “Oh, my dear, it was too big to be a secret to keep for long. I thought of it as a gift—one I could always magic away if you didn’t like it.”

“Well, I don’t like it,” Aurora said.

“Only consider,” said Maleficent, “your borders are protected with no expense to your treasury. No knights need to patrol. No neighboring kingdom can engage in raids. Even brigands and robbers will quail when they realize there is no great distance they can run without trying to pass through a sinister, yet beautiful, hedge.”

Aurora did not appear mollified. “You’re trying to protect the kingdom the way you protected the Moors,” she said. “You put the crown on my head. You have to talk to me before you do things like this. You may have been the protector of the Moors, but you made me the queen of them, remember?”

“I protected the Moors quite well.”

Aurora looked exasperated but changed tack. “What about the storyteller in the market? Is it true you turned him into a cat?”

“Well, it’s not not true,” Maleficent said, a mischievous grin growing despite her best attempts to suppress it. “And just think of the stories he will have to tell now! Why, the more I think about it, the more I’m convinced that I’ve done him a favor.”

“Turn him back,” Aurora told her.

“Just as soon as I can find him,” Maleficent promised, gesturing to the expanse of moorlands, the foggy pools and hollow trees in which a hundred cats could hide. “I am sure he’s around here somewhere.”

“And the missing groom?” Aurora asked.

Maleficent shrugged. “Really, I can’t be to blame for everything. You will have to look elsewhere for the boy. And I hope that after today you see that the humans aren’t going to come to love the Moors. They’re not like you.”

“They didn’t even have a chance to see—” Aurora began.

Maleficent snorted. “As though it would have helped.”

Aurora gave her a wry smile. “Well, since you will be looking for the cat anyway, you can keep an eye out for the boy, too. Maybe that will help.”

Maleficent was surprised—and insulted. “I told you we’re not to blame. Had one of the Fair Folk stolen him away, I would have heard of it,” Maleficent told her. “I hope the humans haven’t managed to make you distrustful of us.”

“Of course not,” Aurora said, hopping along a path of stones half sunk in the water with the ease that came from long practice. “But if you found him, it would do a lot to convince the people of Perceforest that we are all on the same side. What happened today showed the lack of understanding between humans and the faeries. Count Alain thought his sister was being insulted, and etiquette demanded he do something about it.”

Maleficent gave her a long look.

“He doesn’t see the wallerbogs as we do, as gentle and mischievous beings,” Aurora admitted. “But I couldn’t help pitying him a little, first to be knocked around by one of the sentinels and then to be saved by you. You had only to fail to intervene and he might have fallen to his death.”

“When you put it that way, I do see I made an error,” Maleficent drawled.

That made Aurora laugh, as though the words were said in jest. Maleficent had only intervened because she hadn’t wanted the tree warrior to be blamed for a human death. Personally, she wouldn’t have minded if he had fallen.

The more Maleficent thought about it, the more she was convinced that Aurora had learned all the wrong lessons from her.

Because Aurora had been wrong about Maleficent. She wasn’t a kindly faerie, no matter how many times Aurora insisted that she was. And at least in the beginning, she’d seen Aurora only as the means through which she would exact her revenge on King Stefan.

It didn’t matter that Maleficent helped Diaval get her milk when she was a baby, or that Maleficent caused some vines to save her when she ran straight off a cliff while chasing a butterfly right in front of those oblivious pixies. It didn’t matter that things had worked out for the best. It didn’t matter that Aurora’s goodness had woken something in Maleficent she’d thought was lost forever.

It was still foolish to try to see the best in those who were wicked.

And most humans had those seeds of wickedness in them, just waiting to bloom.

But there was no making the girl believe that she’d been mistaken in trusting Maleficent. And Aurora was likely to make the same mistake again, probably with that floppy-haired prince who was mooning over her or that arrogant count desperately trying to impress her. She was going to trust in their goodness, and they were going to fail her, perhaps even hurt her.

“Stay here, in the Moors,” Maleficent said impulsively. “Here, where you’re safe. Here, with me.”

“But at the palace—” Aurora began. Before she could get the sentence out, Maleficent lifted her hands, and in a swirl of golden light, a mist that had hovered over one particular area cleared and her palace of flowers and greenery was revealed. Its spires seemed to spin up into the sky.

The girl could not fail to be delighted by it.

Aurora gasped, her eyes widening in awe. Her hand went to cover her mouth.

“Now you have another palace,” Maleficent said, “one the like of which has never existed before and may never exist again. Come, let’s tour it.”

“Oh, yes,” Aurora said eagerly, everything else momentarily forgotten.

Maleficent followed, watching the girl’s skirts billow behind her and smiling. Aurora raced through the flower tunnel. Then she spun around in the great hall, causing a shower of pink petals to fall from the canopy.

When she discovered her bedroom, she stopped to marvel at the columns of twisted tree trunks, at the enormous bed with embroidered blankets stuffed with the spores of dandelions in place of feathers, and to exclaim over her open balconies.

Maleficent could tell she adored the palace. She even allowed herself to feel a little smug.

“It’s so beautiful, Godmother,” Aurora said once they’d toured the entire place, “and I want to stay here with you. But I cannot. If I don’t change the hearts and minds of the humans of Perceforest, nothing else will matter.”

“You’re their ruler,” Maleficent said, “and ours. But you must decide if you will rule like a faerie or like a human.”

“You say that as though there’s only one correct answer,” Aurora replied, kicking a small pebble that was resting near some steps. It rolled over a few times, then grew little legs and scuttled off.

“Perhaps that’s

what I believe,” said Maleficent.

Aurora took her hand, surprising her. It reminded her again of the sweet child Aurora had been—and, for all her height and the crown on her head, still often was.

“I want the humans and the faeries to see that it’s possible to live together fruitfully,” Aurora said, “to have love and trust between them, as you and I do.”

Willful, Maleficent thought. Foolish. Good. But what could she say? Aurora had taught Maleficent gentleness when she’d thought that part of her was lost. Now Aurora believed the world could learn gentleness. It was Maleficent’s fault that Aurora didn’t understand how unlikely that was. But all she could do now was vow not to let the girl get hurt.

And if that meant hurting someone else instead, Maleficent felt perfectly capable of doing it—delighted, even.

It had taken Count Alain’s servants more than an hour to get the mud out of his clothing. And no matter how long he soaked in a bath of scented water, he still felt as though the grime of the Moors were caught under his nails and behind his ears.

He was not a man who was used to feeling foolish. Under King Stefan, his father had amassed a large fortune. The king had required large quantities of iron, which their mines could supply in exchange for gold and other favors. Ulstead, too, had been an excellent trading partner. When Alain had inherited his father’s title, it had seemed like a simple thing to retain their wealth, especially with a chit of a girl come to the throne.

In fact, the new queen had seemed like an opportunity. But dressed in fresh clothing and presenting himself to Lord Ortolan, Count Alain felt far younger than his twenty-eight years. He was embarrassed and furious, and even more furious because of his embarrassment.

The old advisor’s chambers were luxuriant, hung with tapestries and imported silks—a reminder that he had been in power for a very long time, guiding events behind the scenes. Count Alain’s own father had dealt favorably with him.

“Have a seat,” Lord Ortolan said.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

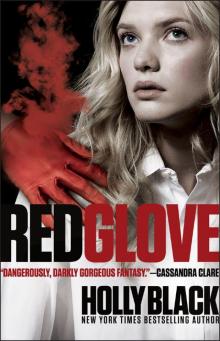

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

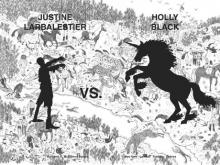

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

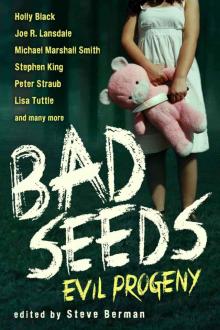

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

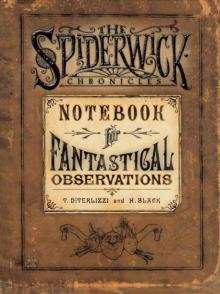

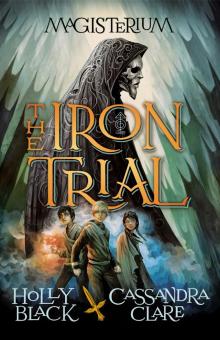

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

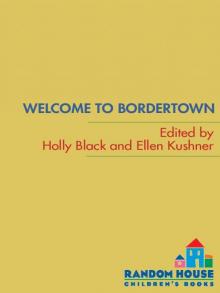

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown