- Home

- Holly Black

The Modern Faerie Tales Page 44

The Modern Faerie Tales Read online

Page 44

Ruddles’s eyes closed with relief too profound to hide.

Long ago, when Roiben was newly come to the Unseelie Court, he had sat in the small cell-like chamber in which he was kept, and he had longed for his own death. His body had been worn with ill-use and struggle, his wounds had dried in long garnet crusts, and he’d been so tired from fighting Nicnevin’s commands that remembering he could die had filled him with a sudden and surprising hope.

If he were really merciful, he would have let Dulcamara kill his chamberlain.

Ruddles was right; they had little chance of winning the war. But Roiben could do what he did best, what he had done in Nicnevin’s service: endure. Endure long enough to kill Silarial. So that she could never again send one of her knights to be tortured as a symbol of peace, nor contrive countless deaths, nor glory in the appearance of innocence. And when he thought of the Lady of the Bright Court, he could almost feel a small sliver of ice burrow its way inside him, numbing him to what would come. He didn’t need to win the war, he just needed to die slowly enough to take her with him.

And if all the Unseelie Court died along with them, so be it.

Corny knocked on the back door of Kaye’s grandmother’s house and smiled through the glass window. He hadn’t had much sleep, but he was flushed and giddy with knowledge. The tiny hob he’d captured had talked all night, telling Corny anything that might make him more likely to let it go. He’d uncaged it at dawn, and true knowledge seemed closer to him now than it ever had before.

“Come in,” Kaye’s grandmother called from inside the kitchen.

He turned the cold metal knob. The kitchen was cluttered with old cooking supplies; dozens of pots were stacked in piles, cast iron with rusted steel. Kaye’s grandmother couldn’t bear to throw things away.

“What kind of trouble did the two of you get into last night?” The old woman loaded two plates into the dishwasher.

Corny looked blank for a moment, then forced a frown. “Last night. Right. Well, I left early.”

“What kind of gentleman leaves a girl alone like that, Cornelius? She’s been sick all morning and her door’s locked.”

The microwave beeped.

“We’re supposed to go to New York tonight.”

Kaye’s grandmother opened the microwave. “Well, I don’t think she’s going to be up to it. Here, take her this. See if she can keep something down.”

Corny took the mug and bounded up the stairs. Tea sloshed as he went, leaving a trail of steaming droplets behind him. In the hall outside Kaye’s door, he stopped and listened for a moment. Hearing nothing, he knocked.

There was no response.

“Kaye, it’s me,” he said. “Hey, Kaye, come on and open the door.” Corny knocked again. “Kaye!”

He heard shuffling and a click, then the door swung open. He took an involuntary step backward.

He’d seen her faerie form before, but he hadn’t been prepared to see it here. The grasshopper green of her skin looked especially strange when contrasted with a white T-shirt and faded pink underwear. Her shiny black eyes were rimmed with red, and the room beyond her smelled sour.

She lay back on the mattress, bundling the comforter around her and smothering her face against the pillow. He could see only the tangled green of her hair and the overly long fingers that pulled the fabric against her chest as though it were a stuffed toy. She seemed like a cat resting, more alert than it looked.

Corny came and sat down on the floor near her, leaning back on a satiny tag-sale pillow.

“Must have been a great night,” he whispered, experimentally, and her ink black eyes did flicker open for a second. She made a sound like a snort. “Come on. It’s the ass crack of noon. Time to get up.”

Lutie swooped down from the top of the bookshelves, the suddenness startling Corny. The faerie alighted on his knee, her laughter so high that the sound reminded him of chimes. He resisted the urge to recoil.

“Roiben’s chamberlain, Ruddles himself, along with a bogan and a puck, carried her back. Imagine a bogan gently tucking a pixie into bed!”

Kaye groaned. “I don’t think he was that gentle. Now, can everyone be quiet? I’m trying to sleep.”

“Your grandma sent up this tea. You want it? If not, I’ll drink it.”

Kaye flipped over onto her back with a groan. “Give it to me.”

He handed over the mug as she shifted into a sitting position. One of her cellophane-like wings rubbed against the wall, sending a shower of powder down onto the sheets.

“Doesn’t that hurt?”

She looked over her shoulder and shrugged. Her long fingers turned the tea cup, warming her hands against it.

“I take it we’re not going to make it to your mother’s show.”

She looked up at him and he was surprised to see that her eyes were wet.

“I don’t know,” she said. “How am I supposed to know? I don’t know much about anything.”

“Okay, okay. What the hell happened?”

“I told Roiben I loved him. Really loudly. In front of a huge audience.”

“So, what did he say?”

“It was this thing called a declaration. They said—I don’t know why I even listened—that if I didn’t do it someone would beat me to it.”

“And they are . . . ?”

“Don’t ask,” Kaye said, taking a sip of the tea and shaking her head. “I was so drunk, Corny. I don’t ever want to be that drunk again.”

“Sorry . . . Go on.”

“These faeries told me about the declaration thing. They were kind of—I don’t know—bragging, I guess. Anyway, Roiben told me I had to stay in the audience for the ceremony, and I kept thinking about how I didn’t fit in and how maybe he was disappointed, you know? I thought that maybe he secretly wished I knew more of their customs—maybe he wished I would do something like that before he had to send someone else on a quest.”

Corny frowned. “What? A quest?”

“A quest to prove your love.”

“So dramatic. And you did this declaration thing? You declared.”

Kaye turned her face, so that he couldn’t read her expression. “Yeah, but Roiben wasn’t happy about it, as in not at all.” She put her head in her hands. “I think I really fucked up.”

“What’s your quest?”

“To find a faerie that lies.” Her voice was very low.

“I thought faeries couldn’t lie.”

Kaye just looked at him.

Suddenly, horribly, Corny understood her meaning. “Okay, hold on. You are saying that he sent you on a quest that you can’t possibly complete.”

“And I’m not allowed to see him again until I do complete it. So basically, I’m not going to see him ever again.”

“No faerie can tell an untruth. That is why it is one of the nice quests given to put off a declarer—no endless labor,” said Lutie suddenly. “There are others, like ‘Siphon all the salt from all the seas.’ That’s a nasty one. And then there are the ones that seem impossible, but might not be, like ‘Weave a coat of stars.’ ”

Corny moved onto the bed next to Kaye, dislodging Lutie from his knee. “There has to be a way. There has to be something you can do.”

The little faerie fluttered in the air, then settled in the lap of a large porcelain doll. She curled up and yawned.

Kaye shook her head. “But, Corny, he doesn’t want me to finish the quest.”

“That’s bullshit.”

“You heard what Lutie just said.”

“It’s still bullshit.” Corny kicked at a stray pillow with his toe. “What about seriously stretching the truth?”

“That’s not lying,” Kaye said, taking a deep swig out of the mug.

“Say that the tea is cold. Just try. Maybe you can lie if you push yourself.”

“The tea is . . . ,” Kaye said, and stopped. Her mouth was still open, but it was as though her tongue were frozen.

“What’s stopping you?” Corny asked.

“I don’t know. I feel panicked and my mind starts racing, looking for a safe way to say it. I feel like I’m suffocating. My jaw just locks. I can’t make any sound come out.”

“God, I don’t know what I would do if I couldn’t lie.”

Kaye flopped back down. “It’s not so bad. You mostly can make people believe things without actually lying.”

“Like how you made your grandmother believe I was with you last night?”

He noticed that she wore a small smile as she took the next sip from the cup.

“Well, what if you said you were going to do something and didn’t? Wouldn’t that be lying?”

“I don’t know,” Kaye said. “Isn’t that like saying something that you think is true, but turns out not to be? Like something you read in a book, but the book turns out to be wrong.”

“Isn’t that still lying?”

“If it is, I guess I’m in good shape. I sure have been wrong about things.”

“Come on, let’s go to the city. You’ll feel better when you get out of town. I know I always do.”

Kaye smiled, then sat bolt upright. “Where’s Armageddon?”

Corny glanced at the cage, but Kaye was already shuffling toward it on her knees.

“He’s there. Oh, jeez. They’re both there.” She sighed deeply, her whole body relaxing. “I thought he might still be under the hill.”

“You brought your rat?” Corny asked, incredulous.

“Can we just not talk any more about last night?” Kaye asked, pulling on a pair of faded green camouflage pants.

“Yeah, sure,” Corny said, and yawned. “Want to stop for breakfast on the way? I’m feeling like pancakes.”

With a queasy look, Kaye began to gather up her things.

On the drive up, Kaye put her head down on the ripped plastic seat, gazing out the window at the sky, trying not to think. The strips of sound-insulating forest cushioning the highway gave way to industrial plants spouting fire and billowing white smoke that blew up until it blended into clouds.

When they got to the part of Brooklyn her mother claimed was still Williamsburg, but was probably actually Bedford-Stuyvesant, the traffic grew less congested. The roads were riddled with potholes, the asphalt cracked and pitted. The streets were deserted and the sidewalks heaped with banks of dirty snow. Only a few cars were parked on the sides of the road, and as soon as Corny pulled up behind one, Kaye opened the door and stepped out. It was strangely lonely.

“You okay?” Corny asked.

Kaye shook her head, leaning over the gutter in case she vomited. Lutie-loo’s tiny fingers dug into Kaye’s neck as the little faerie tried to keep perched on Kaye’s shoulder. “I don’t know which part of feeling like shit is from riding for two hours in an iron box and which part is from a wicked hangover,” she said, between deep breaths.

Bring me a faerie that can tell an untruth.

Corny shrugged. “No more driving for the whole visit. All you have to do now is put up with riding on the subway.”

Kaye groaned, but she was too tired to smack him on the arm. Even the streets stank of iron. Beams of it propped up every building. Iron formed the skeletons of the cars that congested the roads, clogging them like slow-moving blood through the arteries of a heart. Gusts of iron seared her lungs. She concentrated on her own glamour, making it heavier and her senses duller. That managed to push away the worst of the iron sickness.

You’re the only thing I want.

“Can you walk?” Corny asked.

“What? Oh, yeah.” Kaye sighed, shoving her hands into the pockets of her purple plaid overcoat. “Sure.” Everything felt as if it were happening in slow motion. It took effort to concentrate on anything but the memories of Roiben and the taste of iron in her mouth. She pressed her nails into the flesh of her palm.

It is a weakness. My affection for you.

Corny touched her shoulder. “So, which building?”

Kaye checked the number she’d written on the back of her hand and pointed to an apartment complex. Her mother’s apartment cost twice as much as one they’d lived in three months ago in Philadelphia. Ellen’s promise to Kaye that she’d commute to New York so they could stay in New Jersey had lasted until the first huge fight between Ellen and her mother. Typical. But this time Kaye hadn’t moved with her.

They walked up the steps to the apartment entrance and leaned on the button. A buzzer droned and Kaye pushed inside, Corny right behind her.

The door to Kaye’s mother’s apartment was covered in the same dirty maple veneer as the others on the eighteenth floor. A gold plastic nine stuck to the wood just beneath the peephole. When Kaye knocked, the number swung on its single nail.

Ellen opened the door. Her hair was freshly hennaed the same rootless red as her thin eyebrows, and her face looked freshly scrubbed. She was wearing a black spaghetti-strapped tank and dark jeans.

“Baby!” Ellen hugged Kaye hard, swaying back and forth, like the number on the door. “I’ve missed you so much.”

“I missed you, too,” Kaye said, leaning against her mother’s shoulder heavily. It felt weirdly, guiltily good. She imagined what Ellen would do if she knew that Kaye wasn’t human. Scream, of course. It was hard to think beyond the screaming.

After a moment, Ellen looked over Kaye’s shoulder. “And Cornelius. Thanks for driving her up. Come on in. Want a beer?”

“No thanks, Ms. Fierch,” Corny said. He carried his gym sack and Kaye’s garbage bag of overnight things into the room.

The apartment itself was white-walled and small. A queen-size bed filled up most of the room, pushed up against a window and covered in clothing. A man whom Kaye didn’t know sat on a stool and strummed a bass.

“This is Trent,” Ellen said.

The man stood up and opened his guitar case, settling his instrument delicately inside. He looked like most of the guys Ellen liked: long hair and the stubbly beginnings of a beard, but unlike most, his were streaked with gray. “I got to get going. See you down at the club.” He glanced at Corny and Kaye. “Nice to meet you.”

Kaye’s mother pulled herself onto the counter of the kitchenette, picking up her cigarette from where it scorched a plate. The strap of her tank slid off one shoulder. Kaye stared at Ellen, finding herself looking for some resemblance to the human changeling she’d seen in the thrall of the Seelie Court—the girl whose life Kaye had stolen. But all Kaye saw in her mother’s face was a resemblance to her own familiar human glamour.

With a quick wave, Trent and his bass guitar swept out into the hall. Lutie took that moment to dislodge herself from Kaye’s neck and fly to the top of the refrigerator. Kaye saw her settle behind an empty vase in what appeared to be a bowl of take-out menus.

“You know what you need?” Ellen asked Corny, picking up the half-empty beer beside her and taking a pull, washing down a mouthful of smoke.

He shrugged, grinning. “Direction in life? Self-esteem? A pony?”

“A haircut. You want me to do it for you? I used to cut Kaye’s hair when she was a little girl.” She hopped down and headed for the tiny bathroom. “I think I have some scissors around here somewhere.”

“Don’t let her bully you into it.” Kaye raised her voice so she was sure her mother could hear her. “Mom, stop bullying Corny into things.”

“Do I look bad?” Corny asked Kaye. “What I’m wearing—do I look bad?” There was something in the way he hesitated as he asked that gave the question weight.

Kaye gave him a sideways look and a grin. “You look like you.”

“What does that mean?”

Kaye gestured to the camo pants she’d pulled off the floor that morning and the T-shirt she’d slept in. Her boots were still unlaced. “Look at what I’m wearing. It doesn’t matter.”

“You’re saying I look terrible, aren’t you?”

Kaye tilted her head and studied him. His skin had cleared up away from so much exposure to gas station fumes and it wasn’t like he�

�d ever been bad looking. “No one in their right mind would choose a mullet as a hairdo unless they were trying to give the world the finger.”

Corny’s hand traveled self-consciously to his head.

“And you have a collection of wide-wing-collared polyester button-downs in colors like orange and brown.”

“My mom buys them at flea markets.”

Picking up her mother’s makeup case off of a mound of clothes by the bed, Kaye pulled out a stick of glittery black liner. “And you wouldn’t look like you without them.”

“Okay, okay. I get it—what if I didn’t want to look like me anymore?”

Kaye paused for a moment, looking up from smudging her eyelid. She heard a longing in his voice that troubled her. She wondered what he would do with a power like hers, wondered if he wondered about it.

Ellen came out of the bathroom with a comb, scissors, a small set of clippers, and a water-stained paper box. “How about some hair dye? I found a box that Robert was going to use before he decided to bleach. Black. Would look cute on you.”

“Who’s Robert?” Kaye asked.

Corny glanced at his reflection in the greasy door of the microwave. He turned his face to the side. “I guess I couldn’t look any worse.”

Ellen blew out a thin stream of blue smoke, tapped off the ash, and set her cigarette firmly on her lip. “Okay, sit on the chair.”

Corny sat down awkwardly. Kaye pulled herself up onto the counter and finished off her mother’s beer. Ellen handed her the cord for the clippers.

“Plug that in, sweetheart.” Draping a bleach-stained towel around Corny’s shoulders, Ellen began to buzz off the back of his hair. “Better already.”

“Hey, Mom,” Kaye said. “Can I ask you something?”

“Must be bad,” Ellen said.

“Why do you say that?”

“Well, you don’t usually call me ‘Mom.’ ” She abandoned the clippers, took a deep drag on her cigarette, and started chopping at the top of Corny’s hair with manicuring scissors. “Go ahead. You can ask me anything, kiddo.”

The smoke burned Kaye’s eyes. “Have you ever thought about me not being your daughter? Like if I was switched at birth.” As the words came out of her mouth, her hand came up involuntarily, fingers curving as if she could snatch the words out of the air.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

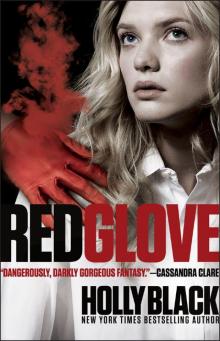

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

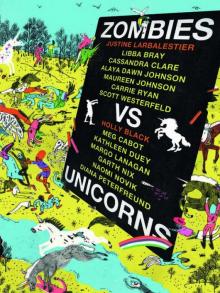

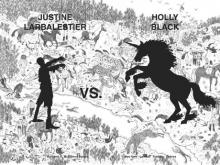

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

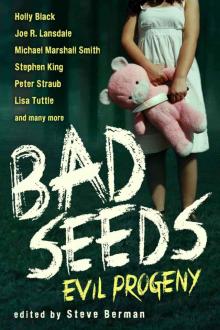

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

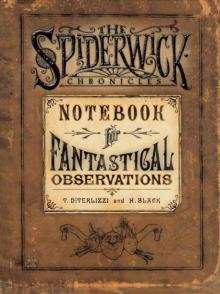

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

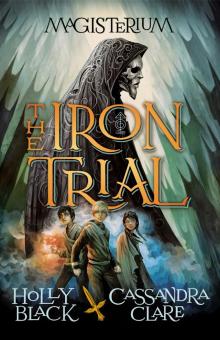

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

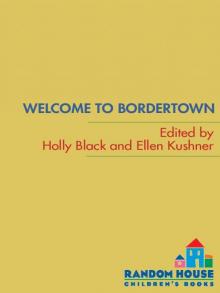

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown