- Home

- Holly Black

Welcome to Bordertown Page 6

Welcome to Bordertown Read online

Page 6

But then he realized he wasn’t. Not tonight.

Tonight he didn’t want to be the observer, standing to the side trying to get others to reveal something. Tonight he wanted to stop trying. Tonight he wanted to be among his own kind.

* * *

I’ve lost track of how long I’ve been here now. They say that time is funny here on the Border, even when there aren’t big thirteen-year gaps, and maybe that’s the reason my days are blurring into each other, suspended in a kind of timeless limbo. Still no Trish. No leads. No fresh ideas. If I wasn’t so cussedly stubborn (Uncle Bud’s words), I’d admit defeat, turn tail, and leave. Bordertown is too big. Thirteen years is too long. My folks need me too much back home.

But Uncle Bud is right: I am cussedly stubborn, and I’m not ready to give up just yet. This town is a puzzle I’ve not yet cracked, an engine whose pieces I’m still learning to fit together. I keep my spirits up by setting myself little daily challenges: to memorize the street map of Soho, for instance, or to learn to tell time by the crazy Mock Avenue Clock, or to figure out how spellboxes run (and, okay, I’m still working on that last one).

One challenge involves The Dancing Ferret. I stop there every evening on my way home—I seem to have grown addicted to a Border brew called Piskies Peri, which The Ferret keeps on tap—and I’m determined to make that snooty elfin waitress smile at me, just once. I use my very best manners: I call her “ma’am,” and I always overtip. She just looks down her nose, flicks back her green hair, and walks off like the Queen of Elfland.

Tonight, a small breakthrough. She plunks down my glass of peri soon after I walk in, without first coming over to ask me what I’ll have. She scowls as she does it, but I give myself two points all the same. I’m a regular now.

It’s quiet at this hour. I like to come well before the first act of the evening begins, sitting in the corner writing postcards home while Rosco snoozes at my feet. The band for tonight, Monkeyshines or something like that, has already set up their gear, their spellboxes, and their special effects. They’re running an illusion spell that’s meant to turn these dark, dusty, shabby rooms into some kind of enchanted sylvan glade, complete with trees rustling in the wind and birds twittering in the foliage overhead. And, yes, it’s weird to use words like “illusion spell” and “sylvan glade” out loud. The uncles would laugh me right out of the house if I came home and actually talked like that, but here that’s how everyone speaks and what they are called. Like I said, we’re not in Kansas anymore.

So I’m sitting writing my uncle Harry on the back of a hand-drawn postcard of Elfhaeme Gate when one of those damn birds tweeting overhead keels over and plops into my drink. I fish it out. It appears to be made of a strange elfin metal, light and pliable, with some kind of a motor inside that is whirring and groaning and ticking faintly.

“Oh, crap,” says the Queen of Elfland, swooping by and plucking the creature from my hands. “They’ve been falling from the ceiling all damn day.” She glares at me like it’s personally my fault as she moves to put the bird into her pocket.

“Wait a minute, can I see that?” I ask. “I’m curious about how they work.”

The waitress snorts (and even her snorts are haughty) as she tosses the bird onto the table. “They don’t work. They just fall down dead.” She whacks it once more for emphasis. “This, sir, is an ex-parrot.”

For a moment I’m so startled by the Monty Python reference that I just sit there like the village idiot as she shrugs and stalks (regally) away. Then I’m turning the bird over in my hands, eager to determine what makes it, well, tick. A latch is concealed in the creature’s belly, which opens to expose a mechanism that is almost clocklike in design—but not like any clock I’ve ever seen. A wickedly clever arrangement of gears and levers is run by an ordinary little motor, attached to a kind of battery. On second look, the “battery” is a lump of wadded-up paper in battery shape. There are words on the paper in a tiny, tiny hand—some kind of spell, perhaps. Or poetry. Or both.

So what, I wonder, has gone wrong here, causing the mesh of magic and mechanics to fail? It could be a faulty spell, or the famous unreliability of Border magic—but my fingers tell me the fault is in the mundane workings of levers and gears and wires. My fingers are never wrong about these things. If it’s possible for human beings to have magic, then my magic is in my hands. Like I said, I can fix almost anything. Even weird little birds with mechanical hearts, drenched in elfin spells and peri.

I have my tool bag with me (of course), and I pull out my smallest screwdrivers, a magnifying glass, an oil rag, and I make a series of small adjustments, testing, listening, trusting in my fingers. Then I’ve got it. I’ve got it. I know what’s wrong, and I fix it with some copper wire, two tiny screws, a piece of gaffer tape, and spit. The sound of the little motor grows steady; the bird flaps its wings, moves its beak, and starts to tweet. I fish out another postcard and write a quick note detailing the repair; then I hand it to the Queen of Elfland as I pay my check. “Tell them it’s an easy fix.”

She almost smiles. “Aren’t you staying for the show?”

I shake my head. I never stay. I go outside to my usual spot, where Rosco and I can sit in the shadows and observe the crowd that is gathering. It’s the kind of crowd I imagine that Trish might like: heavy on the Faerie velvet and lace, on corsets and frock coats and masks and wings. I wait and watch while they all go in. Then I wait and watch all the stragglers, too. Only when it’s clear that Trish is not among them do I rise, whistle for Rosco to follow, and head back to the Diggers’ House.

I’m crossing the street and thinking about a bath (for Rosco, too—that candy smell is strong) when I hear the sound of shouting behind me. Someone is flying out of The Ferret like a bat out of hell—all arms and legs and long silver dreads, the tails of his long coat flapping behind him.

“Wait!” he’s calling, apparently at me. He’s breathing hard as he catches up. A hafling, tall and peculiar-looking, wanting to know: “Are you Mr. Fix-It?”

I look down at my T-shirt, where the words are written in boldface type across my chest.

“You fixed my birds, man! You saved my show! You’ve got to come back and let me buy you a drink!” Now he’s pulling me by the arm, back toward The Ferret—while Rosco, my steadfast protector, merely turns obligingly and heads back to the club. “You’ve got to come see the show,” the tall kid insists as he steers me past The Ferret’s bouncers, past the Queen of Elfland, and past the club’s owner, Farrel Din. “But we’ve got to hustle,” he tells me, pushing through the crowd, “because I’m on in, like, five minutes.…”

* * *

“So you wouldn’t believe what happened!” Trish said. “He opens my bag and goes, ‘Crunchings and munchings?’ ”

“Oh, noooo!” a blue-haired girl screamed happily. “You mean like Gurgi?!”

“Just like Gurgi,” Trish said.

“So what happened?”

“He disappeared.”

“Poof?”

“Not poof. More like—I dunno, like when you take your baby brother to the mall and you turn to look at a store window, and the next thing you know they’re on the loudspeaker going, ‘Will the sister of a little boy in the striped shirt please come to the information desk?’ Only there’s no information desk here, is there?”

The girl shook her head.

“Who’s Gurgi?” asked the guy sitting next to her in the Mumford & Sons T-shirt.

“You wouldn’t understand. It’s a book. You noobs don’t read.”

“We do, too! Who said we don’t read? I’ve read Harry Potter, like, five times!”

“Oh, yeah, and what else? I bet you’ve read whole screens’ worth of text. Like, ‘U R 4 me, imho.’ ” Laughing, the girl drew the letters with her finger on his chest, and they rolled onto the floor together.

Trish looked around for Cam and Seal. They were slow-dancing to a guy playing music in a corner of the room. It looked like he was running a violin

bow across an upside-down saw. Maybe he was. It sounded weird. But they looked so happy. Kind of like Mom and Dad, when they thought the kids were in bed and their favorite song came on the radio … Oh god, were they still all right? What if she never saw them again—

“May I have this dance?”

It was him. The Harvard guy. Wearing incredibly ugly pants and a Star Trek T-shirt, but still. Smiling at her with that beautiful smile.

“Um, I don’t dance,” she said. “Not like that.”

“That’s good.” He sat down next to her. “Neither do I. I just thought it was a great opening line. You know, like in the movies. I’ve never tried a line like that. But I thought, ‘I’m in Bordertown. What do I have to lose?’ ” He held out his hand. “I’m Anush. I mean, I guess you know that already, but I’m being extra polite tonight.”

Was he flirting with her? Or just being nice?

“Trish,” she said, shaking his hand. Oops. “But my name here is Tara.”

“That’s a pretty name.” His eyes were so dark, his lashes so thick.

“Why didn’t you pick a new name?”

“Well, I wanted Legolas or Gwydion, but …” He shrugged and grinned. She understood.

“Can I ask you something?” Trish said. “I don’t mean to be rude, but … where are you from?”

“California.”

“No, I mean before that.”

He gave her a long, cool look. “My parents came from India, if that’s what you’re asking. But I was born here—like you.”

“We weren’t born here. Either of us. This is Borderland.”

He picked at a frayed thread on one of the tiny whales on his pants. “True. And we both came here on a quest to learn something, didn’t we?”

“You too?”

Anush nodded. “Oh, yeah. See, when I left … I thought …” He worried at the thread, not looking at her. “I guess I wanted to be Vyasa and Ganesha, both at once—” He stopped. “You don’t know anything about them, do you?” Trish shook her head but kept her eyes on his face, hungry to learn. “Vyasa was the man who narrated the great Hindu saga the Mahābhārata, while the god Ganesha wrote it down.” He stopped for a moment. “But Vyasa was part of the story as well. He’s an important character in it, the father of princes.”

“What kind of princes?” Trish asked.

“Oh, the usual kind. Brave, reckless, beautiful, doomed. Indian princes.”

“Did you study that at Harvard?”

“No, my mom used to tell me those stories.”

“Wow, that’s so cool!” said Trish. “The real oral tradition!”

Anush grinned. “But transcribed first by an elephant-headed god.”

“With excellent penmanship. That’s right, you said. So you didn’t read them as part of that class on myth and fantasy literature?”

He picked at the whale again. “Um, no. We only looked at Celtic myth. All the classic fantasy novels are based on that, or Northern European material. Nobody writes about Indian stuff.” Trish nodded. “Kind of too bad, really, because it could be really cool—I mean, Vyasa’s son, Dhritarashtra, for instance, was a blind king; his brother, Pandu, was a great archer, but cursed.…”

This is it, Trish thought as the night went on. This is what I came here for. Maybe not to be in a story, after all, but to hear them. She loved listening to him explain things. She loved watching his hands move and his face shift as he told her of the great war between the two families, of the heroes and the strange and noble women in both of them … while around them at the Chimera there were people singing, dancing, talking, joking, eating, and, maybe, changing their lives.…

* * *

The tall kid has not been exaggerating: He is due on the stage in five minutes. The band has been announced, the house lights are dimming, the birds have commenced swooping (safely) overhead—and I’m soon standing in the wings with a tall, cold peri, Rosco curled up on some coats behind me. Even here in shadows, I feel conspicuous and stupidly out of place in my jeans and T-shirt and old Frye boots, while the band on the stage is all tattered old velvets and lace, like the crowd that’s come to see them. For a moment I think about turning and leaving … but that’s when the music starts.

The tall halfling (whose name, I’ve learned, is Spider) now stands in the very center of the stage, a gangly scarecrow in a coat of elfin cloth worn over an old Scottish kilt and hobnailed boots. His silver dreadlocks hang heavy on his back, speckled with random bits of leaves and moss, and his wrists are weighted with Faerie gold and gems that sparkle in the stage lights. The other musicians are fanned out behind him, each one looking more outlandish than the next—except for a skinny human with a little goatee, dressed so plainly that he’s odd, too. Spider holds a bizarre-looking instrument that must come from the lands beyond the Border: intricately carved and painted, shaped a bit (but not entirely) like a fiddle, its six strings played with a thin white bow that looks twice as long as it ought to.

The crowd falls completely silent as the halfling kid begins with a single note, so soft it is barely audible, and then it slowly, slowly rises in volume until it fills the entire room. It’s not music, exactly. Not what I call music. It’s more like a moaning kind of sound, like wind in a cave, like a woman in the throes of passion, and I can feel that note as well as hear it. It rises, rises … turns from a moan into a groan like boulders shifting deep inside the earth … or a groan of pain, deep inside my own belly, aching and awful and endless. I catch my breath, and all around the club I can hear other people gasping, too—but this, this is my pain; this is my grief. It’s Trish disappearing and the folks growing old too fast and a dozen other deeply private things … and yet it is also everybody’s pain, every person there, shared and multiplied, unbearable … and then suddenly it breaks, like a wave … like window glass shattering into shards of sound and light, and the moaning is now the wind in the trees, and I’ve never felt so free in all my life.

Then a fiddle appears in the skinny human’s hands, its music sliding sideways into the web of sound, of light, of motion and emotion that Spider has been making, conjuring, weaving with his body, his breath, the lightning movements of that overlong bow. The fiddle music, by contrast, sounds almost coarse; it is human, earthy, raw … and powerful due to all those things. It is a sound that my ears can more easily understand as music, and it anchors the elfin sounds and draws them closer to the human sphere. Then there are drums. Maybe two, or five, or ten. Or is it dozens, stationed all around the room? Or maybe it’s just one young woman, dark hands a blur of motion, making all that sound. Next, a flute, or something like a flute, making … noises (not unpleasant, just strange) that I have no words to properly describe. Followed by an instrument that looks a lot like a mandolin, and sounds like one, too.

Overhead the birds add their song to the tapestry of sound and flit through the spectral trees, and I know they’re made of a mishmash of magic and mechanics, but they look so goddamn real. An illusionary wind rustles my hair, and there are tears in my eyes. I don’t know why. I don’t even know if I like this music—it’s too strange, too hard, too sad, too full of longing for something that I can’t even name. But I’m rooted to the spot. And then suddenly the tall kid shouts, and it all changes.

Electric guitars appear onstage, corralling all the other sounds into a danceable beat that is wild and insistent. These are rhythms I know; this is good ol’ rock and roll—so loud, so raucous, and so damn good that all of the kids in the club are now on their feet and they’re shouting, too. Shouting, stomping, clapping, jumping up and down, and dancing. Oh my god, are we dancing, so fast and hard that the floor starts to shake. Okay, I’ve never been much of a dancer—I’m a shuffle-from-one-foot-to-the-other kind of guy—but this music is so good (weird as anything, but good) that I have to move, have to shake it up inside me, and if I look demented, I just don’t care. For the next two hours, I forget about Trish and my folks and every other thing on this earth, and I live only in that mus

ic, in sweat and motion, in that heaving crowd of kids. Trish used to say that dancing can be a sacred thing, and I think that I now know what she meant. Something happens when you share that high, that joy, with a room full of equally blissed-out strangers. You change, they change, and by evening’s end, no one is quite such a stranger anymore. We roar and stomp, and when the set comes to its close, we will not let the band off the stage. They’re back for encore after encore, and I dance and shout and do not want the night to end.

Eventually, however, the last notes of the fiddle fade and the birds overhead grow still. The club grows quiet; people whisper or they leave in silence. No one wants to break the spell. I find my coat, my tool bag, and my sleepy dog. My legs are sore but I am feeling … lighter. I find myself smiling at everyone as I head for the doors, Rosco trotting at my heels. And the Queen of Elfland, who is wiping down the bar, catches my eye and—damn!—she smiles back at last.

I’m heading home when it happens again: Spider bursts through the doors of The Dancing Ferret and comes charging down the cobbles of Carnival Street. “Wait! The night’s not over!” he’s shouting, so I stop and wait for him to reach me. “We’re going to catch Lambton Wyrm’s last set at Sluggo’s,” he tells me, “then grab some food from Taco Hell. There’s an after-party at the Chimera … and then an after-after party after that. Come with us. Come meet the rest of Widdershins, my band. The night is young, my friend!”

I hesitate. I don’t know this kid at all.…

He grins. “Don’t worry. Us halfies don’t bite.”

“No, it’s not that,” I tell him quickly. I don’t care about that; I’m just cautious by nature—or at least that’s how I was back home. But here? I find myself smiling easily at Spider. “What the heck,” I say. “Sure. I’ll come along.”

Spider takes my tool bag onto his own shoulders and is chattering away now as we go back up the street. “We’ll stash this at The Ferret. It’ll be as safe as houses. And the dog can come along with us, no worries. They’ll love your pooch at Taco Hell … maybe not at Sluggo’s, but, hey, we’ll get him in. Look at those stars, my man! That moon! It’s a glorious night, and it’s only just beginning! It’s Jimmy, right? People call you Mr. Fix-It, did you know that? Groovy shirt. That vintage truck-stop look is cool. My drummer thinks you’re cute, but, hey, don’t tell her that I told you. Here’s The Ferret. Let’s drop this off and … wait, where’s Yidl? Did he leave already? Balls! No, there he is. Yidl! Come meet Jimmy. He’s Mr. Fix-It. You remember. He’s the guy I was telling you about.”

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

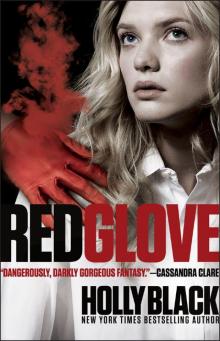

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

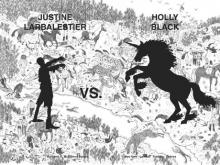

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

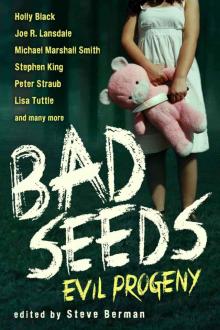

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

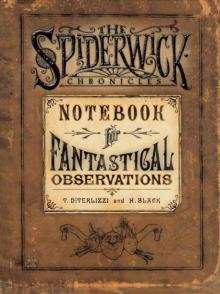

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

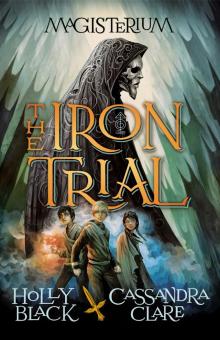

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown