- Home

- Holly Black

Heart of the Moors Page 6

Heart of the Moors Read online

Page 6

“So there is a dish missing?” Aurora asked.

“A large jardiniere,” said Hugh.

She thought of Simon’s family denying even the possibility he’d been involved in wrongdoing. Believing he’d been taken by faeries. They wouldn’t want to believe this.

“So where is he?” Aurora asked. “Thief or not, he’s still missing. And he’s still very young.”

Smiling John shook his head. “We found the stolen horse—which led us to one of the brigands, who was trying to pass it off as his own. He’s imprisoned now and claims not to know Simon’s whereabouts. Our people are still looking. The boy could be lying low. But there’s the more likely possibility that the brigands, once done with him, did away with him, if you catch my meaning, Your Majesty.”

“Do you think that’s what happened?” Aurora demanded.

“No way to know,” said the castellan, “until we find him, alive or dead.”

Aurora nodded. The day had just begun and already she was weary. “Then do so,” she said. “Find him. And soon, before the trail goes cold.”

Many more meetings followed.

Three boys had caught a flower faerie in the Moors and were keeping her in a birdcage. They’d been spotted exiting back into Perceforest, and one had gotten cursed with a foxtail and a pair of fox ears. The Fair Folk were demanding the flower faerie be released, and the boy was demanding that his curse be removed. The faerie herself was demanding a seven-year supply of honey for her trouble.

A cow had gotten lost and then wandered home with braided flowers around its neck and a tendency toward producing more cream than milk. The cow’s owner wanted to know if something would happen to her if she drank it.

With each new accusation, Aurora felt the treaty unravel further. It was only a matter of time before something truly terrible happened—before blood was shed and the humans and Fair Folk returned to being at war, with her unable to halt it.

Finally, Lord Ortolan gave her one piece of good news. Maleficent’s black rose hedges had stopped growing, although they showed no signs of receding. “And they give off a distinct scent. It has been described as musky and not unlike the scent of spoiled plums, with a heady sweetness. Is it dangerous?”

“Let us hope not,” Aurora said with a sigh. After the conversation about the brigands, she couldn’t help feeling that perhaps Maleficent had had a point about the safety of Perceforest’s borders. “Tell me, is there anything we can do to lessen people’s fear of faeries?”

Lord Ortolan’s eyebrows rose. “I understand that you’ve grown used to them, but they are not like us. They’re not human. They’re immortal, with powers we don’t understand.”

Aurora nodded, not in agreement, but with the understanding that he had no interest in helping. “I think a new approach to the treaty must be taken. I wish to hear from my subjects on their concerns—and superstitions—about the Moors.”

Lord Ortolan looked alarmed. “Your Majesty, begging your pardon, such a thing could take many, many days to arrange. Your court, of course, comprises many persons from influential noble houses already who have weighed in on the treaty negotiations, and we have sent drafts to those who have the largest estates and the most riches. But for this, they would have to travel here. And we would have to prepare for their arrival—” He stopped at her expression.

Aurora had had enough. “I have spent enough time in consultation with the nobles,” she said. “Now I want to hear from the rest of my people.”

“Your kingdom is very large, Your Majesty,” Lord Ortolan began.

“Let us start here, then,” she said, “close to the castle. I wish to speak with farmers and tradespeople. This afternoon.”

“This afternoon?” Lord Ortolan repeated faintly.

Aurora smiled at him. “I will have town criers sent out immediately to invite people to the castle. And I will go tell the cooks we will need much in the way of refreshment. Perhaps you can send someone to gather up some of those new black roses? They will make marvelous decorations.”

Aurora paused. “But I need to talk to more than just the humans. I will send a message to the Moors that I want to talk to the faeries this evening. I am sure they have fears and superstitions, too.”

With that, she left him looking as though he itched to overrule her, perhaps even scold her. But he couldn’t, and they both knew it.

By that afternoon, Aurora had grown nervous. As she had hoped, many tradespeople and farmers had been willing to take the small payment she’d offered to make up for a day’s work, and were busily eating from the spread of cold meats, bread, and pies she’d provided. She was pleased to see that Hammond, the farmer who had been poaching in her forest, had come, although he stayed at the back of the crowd.

She knew she had to stand up in front of them.

She knew she had to listen to them, even if she didn’t like what they had to say.

But if she didn’t find a way for the faeries of the Moors and the humans of Perceforest to think of themselves as no longer at war, it wouldn’t be long before someone did something so terrible that they were back at each other’s throats again—this time permanently.

Aurora walked into the great hall and went to her throne. Gone were the winged gold lions that had once been there; her new one was simple and elegant, cut from a block of marble. As she sat, a hush fell over the villagers. She saw their gazes go to the crown shining on her brow.

“People of Perceforest,” she said, “you may know me as the daughter of Queen Leila and King Stefan, but remember that I was raised by my aunties and my godmother, faeries one and all.”

She saw the surprise on their faces and wasn’t sure if they hadn’t believed the tales or were merely astonished to hear Aurora herself confirm them. “Now I am not just your queen, but theirs. The queen of the Moors. And I want all of my subjects to come together. For decades, there has been enmity between the humans and the faeries. Why?”

For a moment there was only silence in that echoing hall.

Then a man stood. “We keep clear of the Moors. Those faeries steal your children, sure as anything.”

Aurora saw some grim nodding in the crowd and heard a few murmurs of the missing groom’s name. She wanted to tell them what she’d learned from Smiling John, but they had no reason to believe her, at least until Simon was found.

A townswoman with dark skin and green eyes stood up. Aurora recognized her as a worker from the buttery. “They lead you around in circles,” she said. “So you can’t find your way home even on your own land.”

“Or put you under a curse,” said a young girl with red cheeks and an abundance of curls. As she spoke, she was looking at Aurora as though she expected her to well understand the dangers of being around faeries.

“They aren’t all like that,” Aurora said, thinking of how she had said much the same thing about humans to Maleficent—and might have to say something very similar to the rest of the faeries that night.

But the townsfolk and farmers all had heard the story of Aurora’s curse; all knew she had indeed pricked her finger on the spinning wheel, knew that only True Love’s Kiss had saved her. Some of them might have fought beside King Henry.

“They’re greedy,” said a boy. “They have treasure in the Moors, and they won’t share it with us.”

Aurora looked at him sternly, wondering if he had been involved in the kidnapping of the flower faerie, if it was his friend who had been cursed with ears and a tail.

“I’ll tell you a story of what happened in my neighbor’s house,” said a farmer with a scraggly beard. “There was a girl who preferred to gossip with her sisters rather than do her chores. Well, she figured out that if she left out a bit of bread and honey, one of the faeries would milk the cows and gather the eggs and feed the pigs. But one day her brother came upon the food and, not knowing what it was for, ate the bread and honey before the faerie could get it. And do you know what that creature did? Cursed the boy, even though it wasn’t

his fault! Now any milk curdles as soon as he comes near it. The lad makes good cheese, but it’s still a shame.”

“The faeries frighten us,” said a woman in a stained apron, putting her hand on the man’s arm.

“It wasn’t always that way,” said an elderly woman with a patch over her eye. Her gray hair was pulled back into a bun, and her clothes were homespun. As she stood, the room quieted.

“Nanny Stoat,” several people whispered.

“When I was a little girl, before King Henry came to the throne, we’d seek out faeries for a blessing when a child was born. Many of us would leave out food—and no silly boy would think to eat an offering placed on a threshold—for the Fair Folk are a hardworking people and bring luck with their favor. Used to be that you’d not dare to deny succor to a stranger for fear of giving offense to the ‘shining ones’—for that’s what we once called them in those simpler times.”

Aurora rose from her carved wood throne and walked to Nanny Stoat.

“What changed?” she asked.

“King Henry led us into a war,” she said, “and we forgot. The younger generations only knew the faeries as enemies. And though we have always wanted the same things—enough food in our bellies to be strong, enough warmth in the winter to be hale, and enough leisure to have joy—things are different. The nobles take our best crops and demand taxes besides. And they say they need to do it because they need to protect us from the Moors.”

“Let me try to remind you of those days,” Aurora said, an idea coming together in her mind. “I want you to be able to meet one another in peace. And get to know one another without fear. I have been preparing a treaty to help create laws—so that you don’t have to be afraid of them and they don’t have to be afraid of you….”

Aurora spotted Prince Phillip on the other side of the hall, walking down the stairs with a book tucked under his arm. He glanced in her direction but avoided meeting her eyes. There was something in his face she couldn’t interpret. Perhaps discomfort.

For the first time, she saw the motley assembly of people in her great hall through the eyes of an outsider. She took in their sunburned faces and mended clothes. Could Phillip think that speaking with them herself wasn’t a proper thing for a queen to do? That they were not worth hearing?

No, not Phillip. He couldn’t think something so terrible. He wasn’t like Lord Ortolan.

Aurora realized that she’d paused long enough for people to notice and forced herself to keep talking. “I will hold a festival for everyone,” she said, “two days hence. We will have dancing and games and food. And we will sign that treaty.”

That meant she needed to finish it. And she needed to persuade everyone it was in their best interest to abide by it.

At the mention of a festival, a ripple of excitement had gone through the crowd. A few of the young people clasped one another’s hands and began to whisper until they were shushed.

“We and the Fair Folk?” Nanny Stout asked. “Together?”

“Yes,” said Aurora. “Please come, all of you.”

Lots of voices rose then, talking over one another. There were many questions and worries, all of which she tried to address. By the time she left the great hall, she believed most of her people would come, even if it was only out of curiosity. Now she just had to convince the faeries.

And Maleficent.

No matter how difficult it was sometimes for Aurora to accept that she, who had never set foot in the palace until a few months before, was now the queen of Perceforest, it was still harder to get used to the idea that she was queen of the Moors. She suspected the Fair Folk found it hard to get used to, too. They were accustomed to following Maleficent, their defender, and if they did consider Aurora to be their ruler, it was only because Maleficent had ordered it.

In the Moors, Aurora felt like a little girl.

Especially when she found herself holding up her skirts and jumping from stone to stone, giggling as she dodged mud from the wallerbogs—including the one that had escaped Count Alain’s arrow. Then she was speaking with the enormous tree sentinels and scratching under the jaw of the stone dragon. Mushroom faeries and hedgehog faeries, a little foxkin in a drooping hat, and a hob with grass growing from the top of his head all scampered out of their nests and holes.

Eventually, tired out, she rested on a patch of moss as they gathered around her.

Had these creatures, whom she had thought of as friends, truly stolen away children from Perceforest? Cursed those boys? As comfortable as she felt here, Aurora knew that didn’t mean the Moors didn’t have secrets. She knew that war had been waged on them and that they had fought back.

“I came here tonight to ask you what you think about humans,” she said.

There were a lot of frowns exchanged and some snickering.

“Yes,” she said, “I know I am a human. But I won’t get angry. I promise.”

Diaval arrived at that moment, walking out of the shadows with a small wizened faerie called Robin by his side.

“Such a human thing to promise,” said Robin, “when you can no more choose how to feel than a cloud can choose when to rain.”

“I will try not to get angry,” said Aurora.

One of the hedgehog faeries stepped forward, giggling. “I think they want our magic.”

“And our rocks,” said a water faerie, popping her head from the stream. “They want to slice them up and wear pieces of them on their arms and around their throat. Or melt them and make them into rings and crowns.”

“They smell funny,” said one of the wallerbogs, which seemed rich, coming from a creature who spent so much time in mud.

“And they’re loud,” said Balthazar, one of the border guard.

“They get wrinkly fast,” said Mr. Chanterelle, a mushroom faerie, “the way fingers do in water. But their faces, too!”

“That’s called getting old,” Aurora said.

The mushroom faerie nodded, seemingly pleased to be given a name for it.

“They hate us,” said Robin with a frown. “That’s what I dislike about them most.”

Aurora sighed. “The humans are afraid. They told me stories about stolen children and curses. Are any of those true?”

There were a few murmurs from around the glen. Diaval gave Robin a knowing look. The little faerie frowned. “Sometimes we come upon a child in the woods, unwanted and uncared for. Infants, even. We might take that child and raise it here in the Moors. Who can blame us for that? And sometimes we find a child who would be better off in the Moors. We might take that child, too.”

Aurora couldn’t dispute that some children weren’t cared for and that some parents weren’t kind. But she also knew that faeries might not agree with humans about which children would be better off stolen from their families.

“Sometimes,” Aurora allowed. “But what about the other times? And what about the curses?”

“We can’t deny that we have cursed humans,” said Robin. “We are a tricksy people, and the humans have given us plenty of cause. Do they not hunt us? Do they not try to trick us out of our own magic and steal what is ours? We are the ones who should be afraid. They want all we have and all we are—and they want us dead.”

“I am a human and I adore you,” Aurora said, kissing Robin on top of his head and making him blush. “I have heard stories that humans and faeries weren’t always at odds, that there was a time before King Henry when you lived with mutual respect.”

There was some mumbling and some reluctant nodding.

“For the humans that was a very long time ago,” Aurora went on, “but it can’t be so long for all of you.”

“Once, it was different,” the water faerie said grudgingly. “Then, if they wanted my rocks, they would trade for them.”

“And their children would play with us,” said one of the wallerbogs.

“And they would leave us treats,” said one of the hedgehog faeries. “And we would leave them presents in return.”

“Yes!” said Aurora. “And it can be like that again. I know it can. That’s why we’re going to have a festival. Games and dancing and feasting, with humans and faeries in attendance. And the treaty, finished and ready to be signed.”

The Fair Folk blinked at her with their inhuman eyes. There were a few murmurs around the glen.

“Please,” she said. “Please come.”

Maleficent swept into the clearing, holding a black cat in her arms. It butted its head against her dark gown. Her long nails swept down its spine, making it purr loudly. “Oh, my dear,” she said, “nothing could keep us away.”

Her arrival and declaration seemed to signal the meeting was over. The water faerie slipped back into her pool. The wallerbogs began to squabble with one another. A hedgehog faerie scuttled into a nest to take cover. Robin seated himself on a rock and began to carve the top of a long stick, turning it into a staff.

“Is that the—” Aurora began.

“Your storyteller,” Maleficent said, lifting the animal in her arms. “But he seems quite content being a cat. He didn’t seem nearly so happy as a human.”

“No one is,” said Diaval. “A dragon, however? That I wouldn’t mind doing again.”

“Turn him back,” Aurora said.

“I warn you,” said Maleficent, “I didn’t much care for his stories.”

“You astonish us,” Diaval returned. She gave him a sour but not entirely unamused look.

Maleficent let the cat half jump, half drop from her hands. It gave a yowl as it landed in the grass. Then it sniffed the air, as though it had caught hold of some particularly interesting smell.

Maleficent made a gesture with her hands as though flicking water from them. The cat began to grow, and the fur peeled back from a man dressed in traveling clothes. He looked around in confusion and then horror.

“You—you nightmare!” he said to Maleficent.

She gave him a wide smile, clearly delighted by his distress. “What a lovely thing to say! Now, mind, don’t annoy me again or there’s no telling what I might do. Perhaps you might like to try being a fish this time.”

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

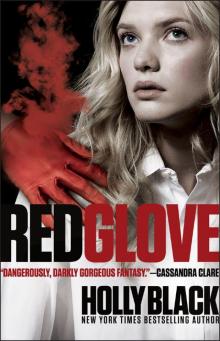

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

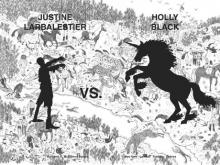

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

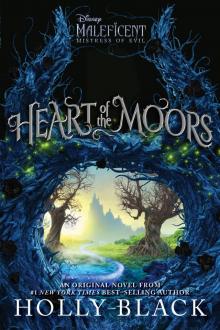

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

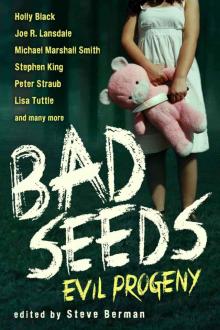

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

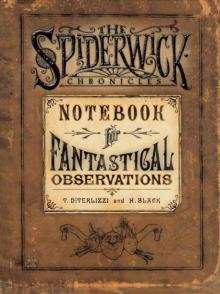

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

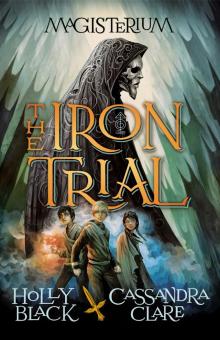

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

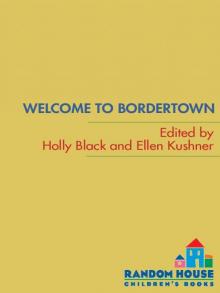

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown