- Home

- Holly Black

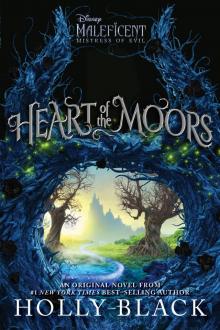

Heart of the Moors Page 12

Heart of the Moors Read online

Page 12

“Including some common enemies,” Nanny Stoat said, glancing at the advisor.

Aurora didn’t have time to dwell on that. She went into the tent and quickly exchanged clothing with Gretchen.

As they returned, Gretchen was still marveling over an embroidered silken slipper. Hammond smiled to see her dressed in such finery.

“Your Majesty,” he said as Aurora was about to head for the stables, “there’s something—not sure if it’s important…”

She paused.

He reached into a sack and brought out a knife. Then he held it out to her hilt-first. “I found this.”

The knife didn’t appear to be very sharp or finely made. The metal was dull. She frowned at it, growing angrier by the moment. She had explicitly forbidden weapons. But something else about it bothered her. Iron. It was a knife forged of cold iron.

The thing was an affront. And the person who had brought it wanted to disrupt the treaty, and maybe do something far worse than that.

“He won’t get in trouble, will he?” Gretchen asked, her hand on her father’s arm.

“Of course not,” Aurora said. “Why would he?”

“It was one of the nobles who dropped it,” Hammond said. “But I knew he’d deny it if I told a guard.”

“Can you describe him?” Aurora asked.

Hammond frowned. “Not his face. But he was a young man with light brown hair, dressed in blue. For a moment, I thought he noticed he’d dropped the weapon, but then he kept on walking. Like maybe he was getting rid of it.”

Aurora turned the knife over in her hand, wondering if it had anything to do with Maleficent’s disappearance. “I’m glad you told me.”

After that, Aurora went to find Smiling John. The castellan was sitting at a long table, a mug in one hand and a portion of eel pie in the other. Soldiers had gathered around him, telling stories of campaigns. They stopped abruptly as Aurora approached.

She didn’t have time to do more than pull him aside and explain the situation briefly. He didn’t like the idea of her riding alone in search of her godmother, and he liked the knife even less, but he eventually agreed to her plans. At least he accepted that Nanny Stoat was in charge, and was willing to reluctantly execute the rest of Aurora’s orders.

Lady Fiora was waiting for her as she walked away from the soldiers. “Everyone is looking for—What are you doing in those clothes?”

Aurora almost laughed. “I’m afraid I must go.”

“No, wait,” Lady Fiora said. “Stay. I hope this has nothing to do with Phillip. There is something amiss. My brother, he—”

“Nothing to do with Phillip,” Aurora said, cutting her off. “And I really, really have to go.”

Aurora led her horse out to the cobbled road in front of the castle and made ready to swing up onto her back.

“My lady,” said someone with a familiar voice. It was Count Alain, leading his own horse from the stables. He had a slim sword swinging from his belt.

“What a surprise,” Aurora said. She wondered if he’d come to intervene on behalf of Lord Ortolan, although he wouldn’t need a horse for that. “I just ran into your sister. You’re very good to see me off.”

“I understand that your godmother is gone,” he said. “You believe she came to misfortune.”

“Her raven is going to lead me to her,” Aurora told him, “whatever has happened.”

“You can’t be thinking of going alone?” he asked.

She put up her chin. “I am.”

“Let me come,” said Count Alain. “No matter what I think of the Fair Folk, I know that no one should ever head into danger without a friend by their side.”

Aurora considered his offer. She thought of all she knew about him, all she feared might have befallen her godmother, and all her godmother’s warnings. But Aurora had already sent Phillip away. She didn’t have it in her to send away anyone else.

“It would be a great kindness if you would accompany me,” she said.

Maleficent woke to pain worse than the iron net had caused, worse than iron chains. Her body burned. Every breath scalded her lungs. There was a spasming tightness in her muscles, and her head pounded so loudly she had difficulty thinking past it. She was in a prison of iron: the floor, the walls, and the bars were all made of the stuff.

“Maleficent?” a voice said, familiar but unsteady. “Is that you moving?”

She realized that she would have been burned worse had someone not put a bundle of cloth under her cheek, had someone not placed her hands so that they were on her chest and not the floor.

On the other side of the cell sat Prince Phillip of Ulstead, pressed against a metal wall. He was awake, his eyes shining in the gloom. His hand was against his side, where she’d seen a blade sink into him. He must be hurt, but perhaps not as badly as she’d feared.

A horn scraped against the ground as Maleficent shifted into a sitting position. She tried to make sure the cloth of her gown was between her skin and the iron floor. Part of her wanted to stand, to declare herself ready for whatever came, but the dizziness she felt just being upright told her how unwise it would be to push herself further.

If only she had her magic…If she had her magic, she would make them all pay.

“Are you badly hurt?” she asked.

Phillip shook his head and then, appearing to think she might not be able to see him, said, “I don’t think so. I got lucky. One of the soldiers stuck a blade through my side, but it went cleanly in and out. I wrapped it with some of my shirt, and the bleeding seems to have stopped.” His tone had the calm, relentless cheerfulness she’d disliked in him, but right then, in the face of unknown dangers, it was a relief. “How about you?”

“The iron,” she said, not even bothering to pretend.

Phillip’s expression was sympathetic, his gaze focused past her shoulder. He couldn’t see her, Maleficent realized. Human eyes weren’t made for darkness.

“Do you have anything that could be a weapon?” he asked her.

“I suppose we could scrape one of your bones against the floor until it was sharp as a knife.” As soon as the words were out of her mouth, she regretted them. It wasn’t an unreasonable question for him to have asked. She shouldn’t be threatening him just because it made her feel a little better.

Although it did make her feel a little better.

A sound came from the door—a scratching, then metal against metal, as though a key was turning in a lock. In the distance, she heard a cry, like that of a boy.

Then the door opened and light flooded the room.

Phillip flinched back, closing his eyes and throwing his arm up to shield them.

Maleficent’s eyes adjusted perfectly well, so she was able to see Lord Ortolan walk into the room with two prison guards holding torches.

She bared her fangs, a hiss crawling up her throat.

Aurora’s advisor had seemed harmless enough to Maleficent: a scurrying scribe, an old man who wished to return to the glories of King Stefan as uselessly and impossibly as he might wish to return to the glories of his own youth. He had seemed a nuisance, nothing more.

How annoying to be wrong.

“Your surprise gratifies me,” Lord Ortolan told her, “as so little does these days.”

“Just what do you think you are doing, locking me in a cage?” Maleficent asked. “Do you hope to keep Aurora from my wicked influence? She won’t thank you for it. In fact, I rather think she will make the little you have left of your life a misery—if I don’t manage it first.”

“Care to make a small wager?” Lord Ortolan said. “Because I’d put the odds on my having more time left to me than you or the prince.”

“Just what do you mean by that?” Phillip demanded.

“With both of you conveniently removed from the palace, little Aurora will marry Count Alain. And when he’s king, there will be no more ridiculousness. He will return to war with the Moors. His iron will once again be in high demand, and the world

will go on as it ought.”

“Iron mines,” said Phillip. “That’s right. Alain has that land full of iron. No wonder he doesn’t want peace.”

“But what do you want, counselor? What will you be given for delivering us into his hands?” Maleficent asked.

Lord Ortolan snorted. “You are mistaken. This is my plan—and he, my pawn. It might have been any of the noble families who worked hand in glove with me in the time of King Stefan and Queen Leila. What I intend is to do as I have always done and have a hand in trade and taxes and tariffs. And when my time is done, I will pass down my role to a nephew whom I have groomed for the part. Gold is always more powerful than iron.”

“How dull,” Maleficent told him. “And how naive. I doubt that proud Alain will want anyone around him who knows what he really did to get the throne. It is not, after all, nearly as heroic a story as murdering a monster from the Moors.” She paused, contemplating. “And of course, that’s all assuming that Aurora will have him.”

“She was once a biddable enough girl,” Lord Ortolan said, although he didn’t sound certain. “And she will be again, following the tragedy ahead. Her dear prince Phillip abducted her godmother and murdered her. Terrible, no? But I’ve made sure the evidence will bear it out. Still, he might have convinced her of his innocence. Unfortunately, he will be slain by her royal guards before she can interrogate him.

“Once you’re gone, she will stop caring so much about the Moors. She’ll make a lovely wife, especially once she has children to distract her. She’s nothing like you.”

Maleficent gave him her most menacing smile, the one that showed off her fangs. “Oh, that’s true enough. She’s nothing like me. But if there’s one thing I know, it’s that it’s very foolish for the wicked not to be afraid of the good. I, for one, find goodness very alarming. And unlike you, Sir Ortolan—or me—Aurora is very, very good.”

Moonlight allowed Aurora and Count Alain to ride over the familiar roads outside the castle until dawn broke. Then they rode through the day, Diaval making urgent circles above them. Toward night, the raven landed on the back of Aurora’s horse and rode there for a while before perching on her shoulder, his black feathers fluttering in the wind.

He led them to the west, and soon they were out of the boggy wet around the Moors and into deep pine forests. But as sunset fell over unfamiliar roads, the way became harder to pick out and exhaustion began to overtake them.

“Are we close yet?” Aurora asked Diaval. Though they’d stopped at intervals to let the horses drink and eat grass, she was sure that they had been pushed to their limit as well. “Caw once if we have much farther to go.”

The raven was silent, making Aurora blink herself alert.

“We ought to make camp for the night,” Count Alain said. “Whatever we must face, we need to be rested for it.”

“Just a little farther,” she insisted.

The moon was bright enough to light their path, Aurora thought. Their horses kept on.

“You’re very determined,” said Count Alain. “Many girls might not be so eager to save the murderer of their father.”

“You weren’t there,” Aurora said. “You don’t understand. She tried to save him, but he was beyond saving. He loved her once and then he hated her, but his hate was some malignant thing, fed by the love. He cut the wings off her back. Can you imagine doing that to the person you cared for?”

Count Alain looked at her with a strange expression on his face. “Ambition drives people to do many things.”

“King Stefan—my father—hung the wings up in his chambers, like some horrific trophy. He spoke to them, as though he was speaking to her—or to himself—I don’t know. The servants told me as much. I think betraying the person he loved most drove him mad.”

Count Alain shook his head. “Faeries have great powers of enchantment.”

“No. I don’t believe he was enchanted,” Aurora said. “I saw him torture her. He had become the monster he let people believe that she was. And yet she would not have killed him. No matter what people believe of her, I know who she really is.”

Alain was quiet, leading his horse on.

“She is kind,” Aurora said. “More than kind. She loved me, despite my being Stefan’s daughter. I don’t know what I would have become without that love.”

“What do you mean?”

“Maybe I would have made the same mistakes my father made,” said Aurora. “Love teaches us how to love.”

Count Alain was silent again for a long moment, as though he was contemplating that. “Although, in that tale, love brought her little but grief.”

Aurora frowned. “You’re right. But that was his fault, not hers. How could she have known? She did nothing wrong.”

Suddenly, the raven sprang from her shoulder into the sky, cawing.

The pine trees had thinned out, and a worn road cut through the terrain. “What is it, Diaval? Are we here?”

But as she looked around, she neither saw nor heard anything unusual.

The raven cawed, landing and pecking at the earth.

Aurora swung down from her horse’s back and walked to the spot where Diaval stood. The raven cawed again, scratching his claws against the soil.

“Where is she?” Aurora asked him. “I don’t understand! Oh, Diaval, if you would just turn back into a man and tell me.”

But that just made the raven jump around more frantically.

Count Alain let out a massive sigh. “We’ve followed this bird for a night and a day. I am afraid it doesn’t know where its mistress is.”

“He knows,” Aurora said, certain. “But perhaps he can’t tell us.”

“Well, if he can’t, then he’s little use.” Count Alain jumped down from his horse.

Aurora paced around the spot, then stomped with one booted foot. “Hello!” she shouted. “Is anyone there?”

Only silence greeted her call.

“Maybe there will be more to see in the morning. Let’s make camp,” Count Alain suggested once more. “I will get up a fire. There was a stream not too far back for the horses to drink from. And we can have a meal and rest a little.”

Aurora wanted to keep going, keep looking, but she had no idea how. Perhaps Count Alain was right. Maybe things would make more sense in the morning. Things often did.

“I’ll gather up some firewood,” Aurora said, glad of a chance to walk after riding for so long.

It was a familiar task, one she’d done often as a child. Along the way, she found a few mushrooms. But as she filled the pockets of her borrowed dress, she thought of the foraged mushrooms she’d eaten in the Moors at the banquet with Prince Phillip.

I love you. I love your laugh and the way you see the best in everyone. I love that you’re brave and kind and that you care more about what’s true and right than what anyone thinks—

If only she could have said something to him before he departed…

When Maleficent was found, she would write to him in Ulstead. Or arrange a state visit. She would find an excuse to see him. And then she would admit that she loved him. And that she’d been afraid.

And she would hope.

The last time she had seen Phillip, he’d been speaking with her godmother. It had been during her dance with Alain, and Aurora could have sworn she saw a smile pulling up a corner of her godmother’s lips.

Aurora stopped abruptly in the woods, recalling the memory again with new significance.

Had Phillip been the last person to see her godmother? Did he know something about her disappearance? Had he been taken, too?

With unsteady steps she returned to the clearing. Count Alain had already kindled a small fire. She set down the wood she’d harvested.

Diaval wasn’t by the fire or circling in the sky. Diaval wasn’t anywhere.

“Have you seen the raven?” Aurora asked.

Count Alain gave a nonchalant shrug. “Went off to find some carrion, I suppose. Or worms. Or whatever they eat.”

Count Alain smiled. “We can do better than that,” he said, rising. From the saddlebags of his horse, he produced a pigeon pie, a bottle of port, and a thick hunk of cheese.

“Oh!” she said. “How did you think to provision yourself so well? You can’t have known you were about to go on a journey.”

He appeared surprised by her question, then laughed. “Yes, well observed! No, I didn’t know I would be venturing out here with you, but luckily I did think I would be riding to my own estates. As I said before, I hoped to convince you to come for a visit. I thought I might ride out and prepare my people for your potential arrival.”

She frowned at that, not sure what to think. Still, she was happy to eat well. Soon the fire was crackling merrily and she was wrapped in a blanket, her stomach full.

“You were good to come with me,” she told Count Alain. “Especially when I know you do not care much for my godmother.”

“I like her no less than she likes me,” he said.

“Do you suppose Prince Phillip could be with her?” she asked. “He was not her favorite person either, but I saw them together when we were dancing. He might have been the last person to see her before whatever befell her happened.”

He frowned. “Phillip?”

“Your sister told me he went back to Ulstead, but what if he only intended to leave? If she was abducted and he was with her, he might have been taken, too.”

Count Alain gave that some thought. “You may be right about Phillip. But I fear he may not be the subject of misfortune, but rather its architect.”

“What do you mean?” she asked.

“Well, about a half hour after you and I parted, I saw Phillip walking toward your godmother, and there was an expression on his face I am not sure I can describe. Grim purpose, perhaps. And there was something in his hand. Some kind of dull metal. If he was the one who took Maleficent, it would explain their going missing at the same time. And it would give Ulstead power over Perceforest.”

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

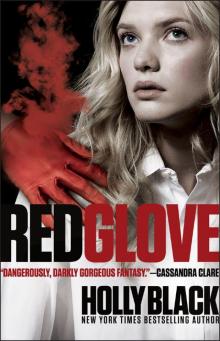

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

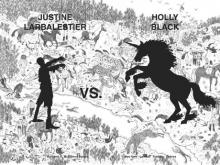

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

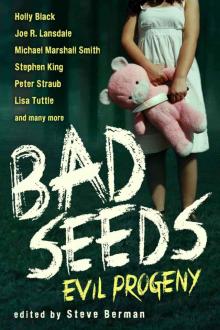

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

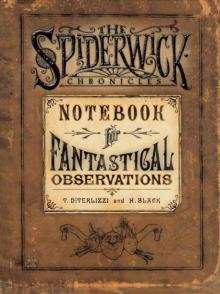

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown