- Home

- Holly Black

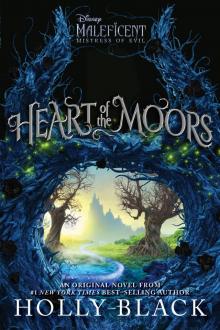

Heart of the Moors Page 13

Heart of the Moors Read online

Page 13

Aurora listened to him in horror, thinking of the cold iron blade that had been found. Surely that couldn’t have belonged to Phillip. Surely he would never do such a wretched thing.

But wasn’t that what Maleficent had once thought about Stefan? Wasn’t that what was so dangerous about love: that it made you vulnerable to betrayal?

Count Alain went on. “If that’s what he’s done, he’s probably making for the border between your lands and his. Perhaps the significance of this place is that it’s where the raven lost the trail. It’s possible Phillip did something to throw us off the track.”

Aurora was trying to think of a reason it couldn’t be true. “But Phillip…”

“Always seemed so kind?” Count Alain said, a slight sneer in his voice. “I have heard things about Ulstead. You may think that your people are suspicious of faeries, but there they are despised.”

In Ulstead, the stories of faeries are even worse than those told here, and there are no Fair Folk to contradict them. He’d spoken those words. But what if he also believed those tales?

Aurora recalled the night she had discovered Phillip in the Moors.

I had to see you, he’d told her. But what if he’d gone there not expecting to find her at all? What if he’d gone for a more sinister reason?

What if he’d spent the entire banquet thinking about how he hated the faeries he was dining with?

What if Aurora’s rejection of him was the final straw? Reluctantly, she thought of Lord Ortolan’s warning.

You may have noticed that Prince Phillip has been dangling after you. I believe he is here to win your land for Ulstead through marriage. Be wary of him.

“I can see I’ve upset you,” said Count Alain.

Aurora picked at the cheese and did not answer.

“We are not so far from my estate,” said Count Alain. “Let’s make for it in the morning. I will put my soldiers at your disposal. If Phillip has Maleficent, we’ll recover her. And if you must make war on Ulstead, your country will be behind you.”

Aurora thought of the moment when she’d discovered Maleficent’s wings trapped in King Stefan’s chamber, beating against their cage as though they were living things, independent of Maleficent. She had felt such immense horror, looking at them.

Before that, Aurora had never understood what great evil truly was. But it looked like chains of cold iron. It looked like King Stefan, hurling Maleficent across the room, intent only on causing her more pain. It looked like a desire to destroy that was greater even than a desire for power or pride.

She tried to picture that expression on Phillip’s face and shuddered. Aurora was the one who had asked Maleficent to trust humans again. If only Maleficent hadn’t loved Aurora, she would be safe now.

Maybe true love was a weapon after all, no matter whom you loved.

“I will save my godmother,” she swore to Count Alain. “No matter who I have to face.”

“I know you will,” he said, taking her hand and gazing deeply into her eyes.

When Lady Fiora had been a little girl, her older brother, Alain, had been her whole world. Their mother had been of a nervous disposition and found an energetic child tiring in all but the smallest of doses. Their father had barely ever been home, busy at the palace in the service of King Henry and then King Stefan. And Fiora’s nurse and tutor had been frequently exasperated with her wildness and inattention. Alain had been the one who taught her how to ride, the one who played games with her, teased her, and made her laugh. In return, she’d worshipped him.

After the death of their parents, she’d begged and begged until he finally brought her to court. There she tried to advance his interests. It wasn’t difficult. Most nobles already admired him, which seemed exactly right. To Lady Fiora, it was Alain’s due that everyone should adore him the way she did. When he’d declared his intention to win the hand of a queen, that had seemed right, too. Of course he would make the best possible king of Perceforest. Of course Aurora would love him.

So when Alain asked Fiora to do certain things, she didn’t mind. Dropping a word about Prince Phillip in Aurora’s ear during the ride through the woods, for example. Or apologizing for her brother. Or encouraging Aurora to choose Alain for her first dance. She was only helping both of them realize they would be perfect together.

And hoping to cheer her brother up. Because despite having brought her to court and occasionally asking her to intercede for him with other nobles, he ignored her a great deal of the time. He’d grown irritable. He would shut himself up with hoary Lord Ortolan for hours on end, becoming quite short with her if he was interrupted. And when he wasn’t with Lord Ortolan, he seemed to prefer to be alone. She’d spotted him heading out on errands late at night, and when she inquired where he was going, his answers were guarded.

Perhaps he’s desperately in love with Aurora, she thought, and redoubled her efforts to push them together.

But at the festival, his mood went from bad to worse. Alain had demanded she tell Aurora that Prince Phillip had left for Ulstead. He’d gripped her hard around the wrist and looked into her eyes in a way that frightened her. But it had obviously been important, so she’d done it.

The moment the words were past her lips and she saw Aurora’s expression, she regretted saying them. Well, she reasoned, trying to convince herself she’d done the right thing, Aurora liked him. They were close. It must be painful to find out he left, but someone had to tell her. And now the way is clear to love my brother.

And yet, as Aurora walked off, Fiora couldn’t help remembering the way that Alain’s fingers dug into her skin and the desperation in his eyes. Just thinking about it made her uncomfortable.

Heart beating fast, Lady Fiora went into the palace and up the winding stairs to Prince Phillip’s rooms. I just want to see for myself that he’s gone, she thought, refusing to closely consider why she doubted it.

And, truly, she expected his rooms to be empty. But when a servant opened Prince Phillip’s door, she peered inside. To her horror, she saw his trunks still resting in one corner. Books were piled up on his desk, beside a half-finished note. A sword was propped against a dresser. If Phillip was gone, why had he left all his things behind?

Fiora tried to come up with some explanation. She knew she ought to say something to Aurora, but what? She couldn’t speak against her beloved brother.

She just couldn’t.

And she tried to stop Aurora from leaving. But when that didn’t work, and Alain rode out with her, Fiora’s guilt grew worse.

Everything had gone wrong, and she didn’t know how to fix it.

That night, Lady Fiora used her key to let herself into her brother’s rooms. His doorframe was marked with a fresh cut in the wood. She ran her fingers over it. Just inside, she spotted a smear of blood at the corner of a carpet.

She knew he hadn’t been hurt, because she’d seen him before he left. But if he wasn’t the one who’d been wounded…

Horrified, she went to his desk, hoping to find answers. Atop it was a silver jardiniere bearing the royal crest, filled with nib pens and blocks of sealing wax. But only the most mundane and dull correspondence was within. His armoire and bedside table were equally orderly. She had turned to go when she noticed that one of the paintings near Count Alain’s bed was askew.

Fiora walked over to straighten it when a thought struck her.

She took the painting down from the wall. Resting it on the bed, she turned it over.

And there, bound to the back of the frame, was a stack of correspondence from Lord Ortolan.

When she took up the first of the letters, her breath caught.

If it weren’t for Stefan’s purporting to have slain Maleficent, your father would have been named King Henry’s heir, it read. Remember that when you kill her. And if the boy follows, make sure you kill him, too.

That night, lying by the fire and wrapped in her waxed cloak, Aurora listened to the crackle of the kindling and turned on the hard grou

nd. With her godmother missing and Phillip implicated in her disappearance, it seemed more impossible than ever that she would sleep. But she had been awake for far too long, and her body knew it. Her eyes drooped closed.

Aurora dreamed she was wandering through the woods. Dawn was turning the horizon gold, and a light frost covered the green plants.

On she walked, her steps crunching frozen leaves. She came to the place where Diaval had stopped the night before. But now the area was covered in ravens.

Closer she crept. The stillness of the forest made her try to be quiet, too.

Dozens and dozens of ravens cawed at her approach. And beneath their shining black feathers, she saw a pale hand sticking out of the freshly turned earth.

Aurora rushed forward. “Godmother!” she cried.

The ravens took to wing at once, in a great rush. Aurora fell onto her hands and knees. A body had been shallowly buried in the soil. Frantically, she brushed dirt away from it.

But it wasn’t her godmother she found.

Prince Phillip lay stiffly, not sprawling as one does in natural rest. His face was turned upward and cold to the touch. His skin was the bluish white of skimmed milk, especially around his eyes and mouth. His chestnut curls still shone, even with dirt in them. Sunlight caught in his lashes, turning them to gold. Yet he remained as still as the grave.

“Wake up,” she said in a whisper. And then, in a shout: “Wake up!”

At her shout, the ravens began to caw from the trees above.

“Be silent,” she yelled at them.

And she knew that this was no enchanted sleep. This was death.

She leaned down. Some of her hair fell over his cheek and throat. Were he alive, it might have tickled him.

Taking a quick breath, she brushed her mouth against his cold, soft lips.

Then, sitting up, she prepared herself to take one last look at him. But when she gazed down, he no longer had the same appearance as before. His lips were no longer bluish, but the pink of the inside of a shell. And as she watched, his skin took on a flush of warmth.

Then, impossibly, Phillip’s eyes opened, and he sucked in an unsteady breath.

“Aurora,” he said, grabbing her shoulder hard enough that it hurt, “run. He’s right behind you. Run!”

No torch burned in the prison. No oil lamp flickered. No window showed the stars. Phillip wasn’t even sure it was night anymore. It was hard to calculate anything in complete darkness. Instead, he sat against the cold metal wall and tried to think.

His side still pained him, but it was a dull pain now, not like the burn of the wound during the ride, when his head had been covered and his hands bound. Then he’d known he was still bleeding and hadn’t been sure how much, only that he could feel the wetness in the way his shirt stuck to him. He’d been passing into and out of consciousness, mostly from shock. And then there had been the brief moment when the bag was pulled off his head in the prison and he’d seen the horror of Maleficent sprawled on the iron floor, her skin burning like she was a piece of meat thrown onto a hot pan.

A moment later, the torches were doused and he was plunged into endless night. He’d bitten at the ropes around his hands until he was free, and then crawled across the floor to Maleficent. He’d shucked off his doublet and pillowed her head on it, using a strip of the lining to bind his own wound. He’d counted to ten and twenty and one hundred, to try to calm his racing heart and focus.

Now that Maleficent was awake, he felt a little calmer. Still, they were in fresh trouble. Phillip had feared they would be killed as soon as they were taken, but something had stayed the hands of their captors. Now he suspected it was only that Lord Ortolan was waiting for Count Alain. Perhaps Lord Ortolan didn’t want to be the one to deliver the order. That way, Count Alain had no opportunity to frame him along with Phillip.

Neither he nor Maleficent had much time. Alain might be arriving any minute.

Lord Ortolan’s plan was remarkably good for being so simple. Even if Aurora suspected the story wasn’t true, there would be no way to prove it once he and Maleficent were dead.

And every moment in the iron prison weakened her further, he was sure. He’d noticed that the instant after Lord Ortolan left, as the last soldier marched out with him, she sagged forward. It must have cost her a lot to hold herself together the way she had, to behave as though nothing touched her.

“How bad is it?” he asked softly.

“I’m well enough, Prince.” Her voice sounded strained, as though she was speaking through gritted teeth. “Or I will be, just as soon as we are free.”

“You’re a bit terrifying,” he said.

“Just a bit?” There was a smile in her voice.

“When I was a child, I saw a faerie—or at least I thought I did. It was a little thing, small enough to ride on the back of a bird. And I believed that if I caught it, it would give me a wish.”

“Why should it do that?” Maleficent said irritably.

“My nurse told me stories about faeries that granted wishes,” he returned. “And I didn’t catch the faerie, of course. But no one even believed that I’d seen it. My mother told me to stop telling lies.”

Maleficent was silent.

“My nurse said that if it had really been a faerie, it would have bit me or put a spell on me.” He gave a long, heavy sigh. “And that if I ever truly saw one, I ought to kill it. So I decided I’d dreamed it.”

“If you are imagining I can wish us out of this, king’s son, you are much mistaken,” said Maleficent.

“When I saw Aurora for the first time, I thought perhaps she was one of you—one of the faeries of legend. She seemed like the answer to a wish. Like a dream. I believed I loved her instantly.”

Maleficent snorted.

“You’re right. I was infatuated. And that callow, lovelorn youth is who you see when you look at me, but I have lived at the palace for months. I have been by Aurora’s side all that while. I have seen her goodness. I have sat with her in the garden when she cannot sleep at night for fear she won’t wake.”

Maleficent made a soft sound at that.

“I do love her. And you need not believe me, but I am going to prove it to you, when I get both of us out of here and save her.”

“You are perhaps not as repulsive a suitor for Aurora as I thought you were,” Maleficent said faintly. “But I will like you better still if you can keep that vow.”

Phillip had made it impulsively and meant it absolutely, but that wasn’t the same as having a plan. And it seemed all he could think of were the things Maleficent would be able to do if only she weren’t surrounded by iron, like bending the bars or perhaps turning him into an ant the way she had turned Diaval into a dragon. Then he could walk out of the prison, get the keys, and free her.

The more he thought and thought without having a single useful idea, the more he felt like the callow youth he had denied being.

But then, after all, he did have an idea.

He would wager that just as Maleficent had entertained an idea of who he was, the guards did, too. They had heard Lord Ortolan call him a prince. So he would behave like one.

“Hey!” he shouted. “Guards! Hullo!”

“What are you doing?” Maleficent hissed.

“I’m cold and hungry,” he informed her, pitching his voice loudly enough to be heard outside the room, “and unused to hardship.”

After a few minutes of Phillip’s shouting as loudly as he could, a guard entered, bearing a torch.

For a moment, the light was so bright that it was painful to Prince Phillip’s eyes. He blinked against it, scowling. But now he could see the room. And he could see that another guard had come in after the first, this one with a set of iron keys dangling from his belt—the same iron keys he’d noticed when Lord Ortolan was giving his speech.

“What’s all this howling for?” asked the guard with the torch.

“We require water and food and blankets,” Phillip said in his best approx

imation of what people thought a petulant prince ought to sound like.

The guards laughed. “Oh, do you now, Your Highness? I suppose you think we’re servants at your beck and call?”

“I imagine that your master would like the full ransom from Ulstead rather than the war he will get if I go missing in the kingdom of the Moors.” The guards shared a glance. No, Phillip thought. Between that look and Lord Ortolan’s words, he could tell they knew he was never intended to go home. “You can’t expect me to believe that ridiculous story we were told about murder. No one would wish to begin their reign by inviting their neighbor to make war on them.”

“You’re probably right,” agreed one of the guards.

“And,” continued Phillip, “even a doomed man is given a last meal. Should your master really mean to put a period to my life, I can’t believe he would do so without feeding me decently.”

One of the guards shoved his torch into a holder with a sigh, relenting. “I’ll see what I can find you, Prince.”

He went out, which left only one guard—the one with the keys.

Perfect.

“What of her?” Prince Phillip said, gesturing toward Maleficent.

“The faerie?” asked the guard, peering at her through the bars as though looking at a dangerous beast.

“You can’t possibly mean to leave me in here with her.”

“Scared?” the guard asked.

“Look here,” Phillip said, beckoning him over. “She’s very ill and she’s constantly moaning with pain. It’s distressing.”

“I will suck the marrow from your bones,” Maleficent shouted, looking up at him with raw anger and showing her teeth. “Then you would know distress.”

Phillip felt a rush of pure primal fear. The guard startled, too. In that moment, Phillip shoved his hand through the gap between bars and grabbed hold of the key ring. He pulled it as hard as he could. It came away in his hand, ripping loose from the leather of the guard’s belt.

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2)

The Wicked King (The Folk of the Air #2) Valiant

Valiant The Coldest Girl in Coldtown

The Coldest Girl in Coldtown The Darkest Part of the Forest

The Darkest Part of the Forest Tithe

Tithe White Cat

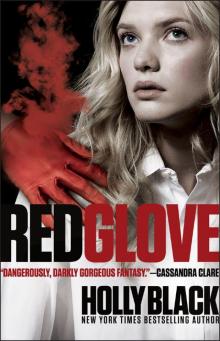

White Cat Red Glove

Red Glove The Cruel Prince

The Cruel Prince Black Heart

Black Heart Doll Bones

Doll Bones Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd

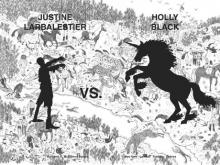

Geektastic: Stories from the Nerd Herd Zombies Vs. Unicorns

Zombies Vs. Unicorns How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories

How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories The Poison Eaters and Other Stories

The Poison Eaters and Other Stories Ironside

Ironside The Queen of Nothing

The Queen of Nothing Modern Faerie Tales

Modern Faerie Tales The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3)

The Queen of Nothing (The Folk of the Air #3) The Modern Faerie Tales

The Modern Faerie Tales Heart of the Moors

Heart of the Moors The Golden Tower

The Golden Tower Tithe mtof-1

Tithe mtof-1 Ironside mtof-3

Ironside mtof-3 The Wrath of Mulgarath

The Wrath of Mulgarath Lucinda's Secret

Lucinda's Secret The Copper Gauntlet

The Copper Gauntlet The Field Guide

The Field Guide Valiant mtof-2

Valiant mtof-2 The Lost Sisters

The Lost Sisters Zombies vs. Unicorns

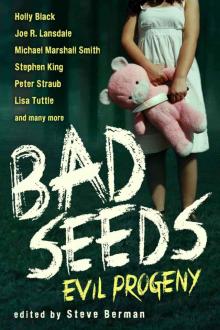

Zombies vs. Unicorns Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny

Bad Seeds: Evil Progeny Red Glove (2)

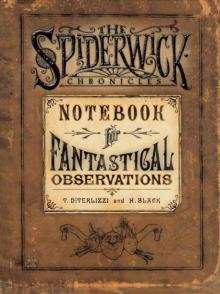

Red Glove (2) Notebook for Fantastical Observations

Notebook for Fantastical Observations The Iron Trial

The Iron Trial Welcome to Bordertown

Welcome to Bordertown